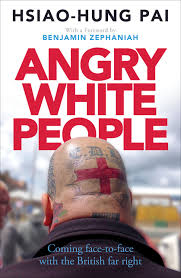

Hsiao-Hung Pai is a writer whose books include Chinese Whispers, short-listed for the 2009 Orwell Prize, Scattered Sand, which won the 2013 Bread and Roses Award, and Invisible, serialised in the G2 section of the Guardian. Her latest book, Angry White People (Zed Books, out 15 March) follows a group of individuals who got caught up in the wave of far right street movements that began in 2009. Delving deep into the day-to-day of the most marginalised section of the white working-class, Pai concludes that their ideologies are not an aberration in modern British society. Here, she discusses the process of researching the book and the conclusions she has drawn.

Why did you decide to tackle this subject?

I’ve always been interested in racism. As an immigrant living here for over 20 years, I’ve always felt like an outsider. I’m still learning about British society and culture. IThis made me want to understand racism. Also my personal experience – the first 10 years I was here, I involved in various campaigns, first of all with the Anti-Nazi League in Cardiff and then when I moved to London I got involved in canvassing against the BNP. I had some contact with BNP supporters and voters, and it always fascinated me why they thought they way they did. I never had the opportunity to really have a conversation with people beyond giving out leaflets – and sometimes people shouting out abuse.

Did the fact that you’re not white British make it harder to do the research?

I was worried at first. I really looked at it as an experiment, I didn’t know what to expect. It wasn’t as bad as I thought . Some people didn’t respond but I managed to have some conversations, and some people agreed to carry on talking with me over a period of time. Of course there was aggression as well, sometimes people would tell me to go away. Actually it was when the project ended that I had more problems – it’s a long story, but there some people got to know about the content of this book and harassed me on social media. I never felt a real physical threat, I felt harassed online, but not directly.

The book is called Angry White People. What are those people so angry about?

I’ll just tell you the story behind this – my idea wasn’t to call it Angry White People at the beginning. As I said I always saw myself as an outsider. In the process of communicating and interacting with them, I feel that somehow they also see themselves as outsiders to their own society. I find that interesting: they feel on the margin of society – a bit how I feel! I actually called the project We the Outsiders. It was changed later by the publisher. Angry White People is about this group of people who come from dying manufacturing working class communities, families who used to vote Labour. These people are mostly in casual flexible employment, they don’t have an identity of any kind of industrial link. The only thing they have is this invented national identity. They are a marginalised section of the manufacturing working class and they feel very alienated in society. That’s where the anger comes from.

Do you think that anger is justified? Did you have any sympathy?

They feel their communities are falling apart, there’s a lack of social housing, a lack of any real opportunities for them to move on and up the ladder. That lack of hope and opportunity is at the centre of their anger. I feel sympathy in that sense: understanding their social circumstances and why they can be drawn into this kind of politics. But at the same time, of course, during the interviews I came across a lot of racist comments. I understand the circumstances and where they’re coming from, but when it comes to the analysis they draw and the solutions they have been led into believing are right for their problems, then obviously there’s a moment when you feel – god! You feel hopeless and depressed when listening to their remarks about Muslims or refugees.

How widespread do you think those ideas are in British society?

There is an interactive process between what I would call extreme racism (I’m not sure everyone agrees with that term) and the racism practised by state policies and media and the rest of it. I call that mainstream racism, and on the other side is the kind of racism we associate with the far right. It continues to interact with and influence each other. Often when you talk to EDL activists, the information they quote is from our mainstream media – the Daily Mail, the Sun and the Express. When the EDL was organising its third demonstration in Tower Hamlets, I asked Tommy Robinson, “where did you get this idea that Tower Hamlets is an Islamic Republic?” – because that’s what he called Tower Hamlets. I live here and I was trying to debate with him about that. He said: “are you ignorant or what? Just check Channel 4 Dispatches”. He asked me to watch a Channel 4 documentary and I did. It was a horrible programme. A lot of EDL guys – that’s how they justify their ideas. Government policies very much reinforce what they are saying against refugees. Recently, when Cameron was talking about getting Muslim mothers to learn English – on the EDL website, people were saying “well done, Cameron is coming along, slowly!” They feel these policies are endorsing what they are saying and doing. I believe that is why people like Tommy Robinson appear so mainstream now – he is talking about trying to appeal to Middle England. He feels that his ideas are being taken on by the media and society, and are acceptable.

Is Tommy Robinson correct to think that the EDL’s ideas are being taken on by politicians?

I don’t think it’s explicit but it’s always there. A lot of the ideas we find in the media are, to be honest, no different to what is said on the far right. It’s one and the same thing. Follow Tommy Robinson on Twitter, what he says is a replica of what we read in the Mail or Express. I myself can’t see the difference. The policies against refugees in this country and all over Europe are also very much reflecting those ideas. Why is Pegida growing across Europe? The ideas are becoming more and more acceptable.

What’s your sense of what the far right today in Britain is like?

The EDL has been in decline since Tommy Robinson left. In the past year it’s got smaller and smaller. Demonstrations are now attended by no more than a couple of hundred of people. The problem is they have so many splinter groups. They are tiny but some are quite violent and they have the potential to do things. But they are small. The bigger worry is groups like Pegida, because they are growing. In Dresden you have tens of thousands of people gathering every week, protesting against refugees. I see that as more of a threat. Thank god that Tommy Robinson’s recent UK Pegida rally was so small! Still, it is a force to be worried about.

Some of those splinter groups have a lot of online support but not actual activity.

Yes, like Britain First – they talk big but on demonstrations it’s a couple of hundred. But social media is such a big thing now. When they launch a smear campaign, that person is going to get it really hard. In the last few months, I have had loads of really abusive comments online, to the point where you just start to feel depressed.

In Britain do you think there’s complacency about tackling these movements?

There’s always a lot of resistance against the far right activities. Since the beginning of the EDL there’s always been counter demonstrations organised by Unite Against Fascism and others, trade unions and local community organisations. People have been resisting now for a long time. These organisations are so important in organising counter-demonstrations and they do a brilliant job, but I think maybe more needs to be done to educate. People need to be given facts to convince them their views are wrong. And there’s a risk of focusing on a tiny minority of people. More needs to be done about more mainstream racism and the practice of the state. Anti-racist campaigners could focus more on what the government is doing to refugees, and push for a positive image of immigration. To push that argument there needs to be agitation and campaigns. But I’m not saying those counter-protests are not important.