This article is a preview from the Autumn 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

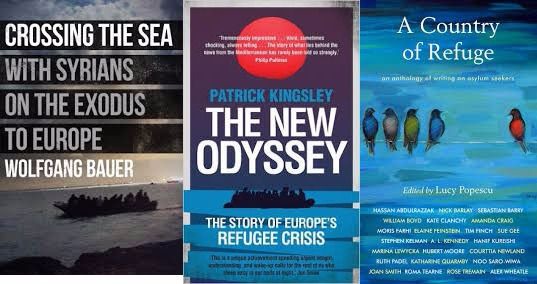

A Country of Refuge (Unbound) By Lucy Popescu

The New Odyssey (Guardian Faber) By Patrick Kingsley

Crossing the Sea: With Syrians on the Exodus to Europe (& Other Stories) By Wolfgang Bauer

“In the current public conversation, this figure [of the immigrant] has not only migrated from one country to another, he has migrated from reality to the collective imagination where he has been transformed into a horrible fiction.” So says Hanif Kureishi in his contribution to the anthology of refugee writing A Country of Refuge.

Each of these three books, in their different ways, attempts to make the return journey back to reality: to a place where the humanity of the immigrant can not only be understood but deeply felt.

Theresa May, our new prime minister, is cited in these books more than any other politician or public figure as someone not only responsible for the UK’s shirking of its moral duty towards those in need but also for the disingenuous stoking of hatred – the “horrible fiction” of which Kureishi speaks – that makes such policy possible. When May said the asylum system was “just another way of getting here to work” she opened up the gates to the hate-speech of Katie Hopkins and her “cockroaches”.

If we are going to make the journey back, we need books like these. Patrick Kingsley’s is perhaps the most traditional. Kingsley has been in a unique position to witness the refugee crisis as it unfolds, due to the Guardian’s foresight in creating a new post of migration correspondent, which he is the first to fill. The New Odyssey is fast-paced reportage crossing a huge terrain: from Eritrea to Sweden, Hungary to Syria, Kingsley zooms in and out of an ever-changing map hosting the biggest movement of people since the Second World War.

Kingsley has woven the book around the journey of one migrant: a Syrian man called Hashem al-Souki. Kingsley calls him an “everyman”, a not particularly political civil servant, compelled to leave his wife and children, risking all for the journey to Sweden. We’re rooting for Hashem, and it’s also a strategy to make the book less overwhelming. Yet it is precisely this feeling of being overwhelmed that brings us closest to the experience of what Kingsley prefers to call the migrant, in recognition that no clear-cut distinction is possible between “migrant” and “refugee” outside legal terminology.

Who is the smuggler, and who the kidnapper? Who is the corrupt coastguard and who the border police? Navigating this world is not only traumatic but tortuously frustrating, before it is, for so many forced to attempt it, fatal. The New Odyssey doesn’t shy away from this complexity. For every “ordinary” man like Hashem, we meet an Abu Hamada, the Syrian-Palestinian, once a refugee, now a smuggler in Cairo, who urges us to see his side of the story.

Ultimately, Kingsley’s message is that we cannot stop this movement. This is a global, complex and shifting phenomenon, both humanitarian crisis and industry, to which “a war on smugglers” is a laughable answer. His proposed solution, for Europe, is a programme of pan-European mass resettlement: “in order to have an impact, the total has to be upwards of a million.” He points out how meagre the EU and the UK’s 2015 pledge of 44,000 was in comparison, together amounting to one per cent of the Syrians who had already left home at the time of writing. To continue with the same non-strategy in the face of such failure, social meltdown and death, he says, is “Einstein’s definition of madness”.

In many ways, Crossing the Sea: With Syrians on the Exodus to Europe could have been a handful of intertwined journeys picked from Kingsley’s work. Yet Wolfgang Bauer and his photographer Stanislav Krupar attempt to undertake the journey across the sea themselves, posing as refugees from the Caucasus. This shared experience, and Bauer’s decision to later risk imprisonment after driving three of his group over the Italy-Austria border, gives the book an intensity and warmth and builds to an ending cri de coeur that is deeply personal: “What kind of people are we, that we watch others drown, day after day?” It’s clear that the book is addressed to us all.

Bauer is invested in his group of would-be refugees, while Krupar’s photography breathes life into moments of the extraordinarily ordinary: we see people, not subjects of history. But we’re left wondering what Amar and Bashar, Alaa and Hussan, might have said for themselves. A Country of Refuge: An Anthology of Writing on Asylum Seekers goes some way to acknowledge this loss of voice. In fact, so many of the 23 contributors are themselves refugees, or their children, that it seems odd not to describe it as a collection “on and from asylum seekers”.

A Country of Refuge brings together poetry, fiction, memoir and essays. The contributions are varied, and are weakest where they tell us what to think, or assume to know what we’re already thinking. Stories like “Selfie”, about a refugee selling selfie-sticks in Rome, or “Hard Luck Story” from the perspective of a detention guard who is himself struggling to stay afloat, are perhaps too obvious – although the Kafka-riff on Katie Hopkins turning into a cockroach is wickedly delightful.

More effective are the contributions that take us around, beneath, beside and between the migration experience, as in the memoir piece “The Dog-Shaped Hole in the Garden”, in which Hassan Abdulrazzak, after fleeing Baghdad as a child for Surrey, is refused a puppy because the RSPCA lady doesn’t trust his family. Or “Shakila’s Head”, where a creative writing teacher struggles to know how to deal with her student’s oddly blithe revelations of trauma.

The anthology ends with AL Kennedy's’s call to arms (a version of a lecture delivered to the European Literary Days festival last year) “to rediscover and restate our full potential as artists” and to “imagine a future” or live with one that “may kill us along the way”. Like Kureishi, Kennedy is talking about a fatal failure of the imagination.

Artists and writers do have a special duty to resist this dangerous cultural impoverishment. Go to the Imperial War Museum today, for example, and you will see an exhibition called “Fighting extremes: from Ebola to Isis”. Put on a par with a sudden outbreak of disease, the current conflict in the Middle East is presented here stripped of all history and human cost. Yet steps away are the World War II displays on the millions that fled Nazi Germany.

Literature and non-fiction have always done this work of building, and connecting, stories. Unlike film – think of The Hurt Locker, or the “hunting Bin Laden” flick Zero Dark Thirty – books have a hard time succeeding at all if they don’t draw on a rich seam of understanding and compassion. In Britain in 2016, understanding is badly needed. These three books are a good place to start.