This article is a preview from the Autumn 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

We are living in an age obsessed with the pursuit of wellbeing. Even the government now regards being happy as a key goal: the UK’s Office of National Statistics measures national wellbeing to gauge policy impact. An increasing number of companies offer workplace wellness programmes, as do some universities and even prisons.

And central to the quest for inner and outer health is the national addiction to slimming. “The ritual of dieting has become an epidemic,” asserts Tim Spector in his new book The Diet Myth. “A fifth of the UK population are on some form of diet any one time, yet we continue to expand our waistlines by an inch every decade.”

Spector himself, a professor of genetic epidemiology, suggests that the reason diets don’t work has little to do with whatever regime you favour or your lack of self-control. It all comes down to the microbes in your gut. These vary from person to person but you need to encourage a balance of good microbes to eliminate the harmful ones.

For Bee Wilson, though, the guilt and self-denial that diets entail are the very reasons why they don’t work. In her new book, First Bite: How We Learn to Eat, she argues that bad food habits are formed very early. And childhood preferences for sweets and over-processed foods remain into adulthood. The answer, she proposes, is to re-educate the palate and, most importantly, to shed the guilt. Forget the endless dieting, and start to enjoy food again.

Which of course sounds easier than it is – not just because Mars Bars are munchier than muesli and cognac has more of a kick than carrot juice, but because the goal we set ourselves is unrealistic. Dieting is the new religion. And, just like religion, it offers an unreachable ideal.

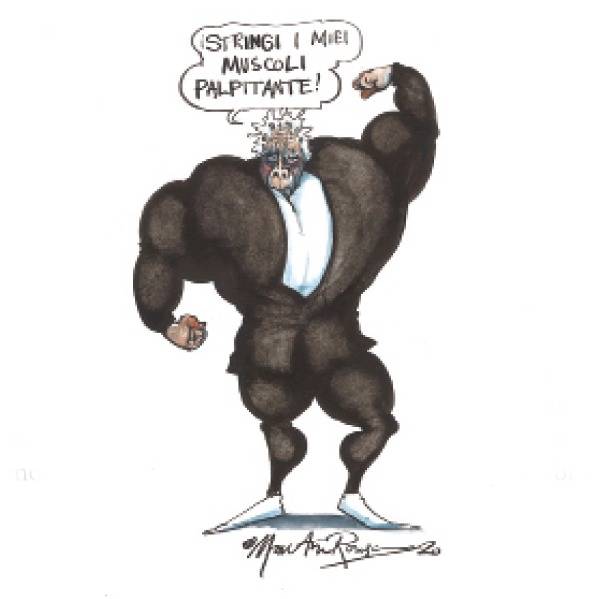

So instead of being a pleasure, eating has become such an elaborate ritual that for many dieters the complexity of the routine has itself become an article of faith. Brandishing their beliefs like stigmata, allowing their habits to turn them into nuns, today’s food purists are as sanctimonious as the religious in their devotion to dietary codes.

Every modern slimming diet will formulate its own set of rules into a metatext of forbidding. No carbs or no fat. Nothing but fruit, or anything but bread. And if you want to be really, really thin you could try Breatharianism, in which you avoid food and drink entirely, and just take in lots of – er – air.

The more precise the rules, the more people like them. The ultra-cool 5:2 diet, which recommends fasting for two days of each week, drives adherents to fanatical calorie-counting on their guilt-inducing Fitbits – last year’s favourite Christmas present for the gym crowd. Another newcomer to the food and fitness world is the Nutribullet – a high-powered blender that will instantly turn to mush even the hardiest pineapple or squash. Green slime, it seems, is the route to slimness and health, provided you include magic ingredients like kale and pomegranate.

All of which rests on the belief that something deeper than mere food consumption is at work. Something that moves in mysterious ways. It’s as if by sticking religiously to the most stringent diet plan you’ll not only achieve the perfect size-zero beach-ready body, but the perfect mind, too. Spiritual cleanliness can be achieved not through prayer and goodness, as in traditional religions, but through weight loss, slimness, fitness. Purity of the body has been converted to purity of the soul through the grace of detox.

“Clean eating is often claimed to have almost miraculous healing powers,” Julian Baggini recently wrote in an article for the Observer. “But its proponents often go beyond physical health, making claims that eating well is good for the soul, too.”

He cites the increasingly influential Hemsley sisters, whose recipes come with a “simple, mindful and intuitive” philosophy. Jasmine and Melissa Hemsley, authors of two cookbooks and with their own television programme, promote the idea of wellness through improving digestion and taking care of the gut. Despite their many followers, they have also attracted critics who regard their approach as simplistic and naïve. Great British Bake Off contestant and cook Ruby Tandoh, for example, recently spoke out against “wellness evangelism”, criticising the perception of food as medicine.

And Baggini is highly sceptical about the contemporary zeal for mindfulness as a route to self-perfection. “Mindfulness in its original form is a difficult, lifelong practice,” he writes. “Mindfulness in Buddhism is practised in the context of an ethical system that places no value on seeking sensory thrills. Expect mindful eating, however, to be presented as an easy panacea for our excesses.”

And this growing fixation with boosting health and wellbeing can backfire. That’s the view of Andre Spicer and Carl Cederström in their new book The Wellness Syndrome. They argue that people are so relentlessly faced with this pressure that they can be overwhelmed with anxiety – and even prejudice. “People who are judged not to be maximising their own wellbeing are considered to be bad people or to have some kind of moral flaw,” they suggest. “Overweight people, for instance, are routinely judged as having other negative characteristics like laziness. As a result new kinds of discrimination based on health and wellbeing are starting to open up.”

So it’s never been more imperative not just to look good but to feel good, too. And the Boadicea of the healthy mind brigade is Gwyneth Paltrow – she who swears by coconut oil and mung beans, claims that condoms are toxic, and whose food preferences, despite her mistrust of proteins, extend to the wilder extremes of nuttiness. The forbidden fruits on her most recent detox diet include red meat, dairy, corn, soy, added sugar, white rice and shellfish. Also, no caffeine, alcohol, gluten, or“nightshade” fruits and vegetables: tomatoes, eggplant, peppers and potatoes.

With her 2.67 million Twitter followers and her bestselling cookbooks, Gwyneth is also the founder of a multi-million pound business, Goop, complete with the inevitable celebrity endorsements. Its central philosophy, the Clean Cleanse, involves bizarre practices like vaginal steaming with mugwort, shower peeing, cooking with sex dust, optimised yawning and fat freezing. She recently announced she would step away to allow Goop to grow, saying “its scalability is limited if I connect with it”. Gwyneth has not only developed a successful brand. She is one. Famous, rich, talented, beautiful and thin, she is the ideal advertisement: eat like me and you’ll and you’ll become like me.

If Gwyneth is the patron saint of spiritual sanctity through food resistance, we now also have our very own saviour, courtesy of the new movie Absolutely Fabulous. In her updated version of the popular television series, Jennifer Saunders – playing of course a now older and even sillier Edina – has tapped into two modern phenomena: the cult of celebrity and the quest for slimness. Edina tries every diet going and repeatedly bemoans her fatness. Meanwhile, the ultimate emblem of perfect womanhood is model and style icon Kate Moss, whose mantra, if you remember, is “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.”

The plot turns on one sublime action – when Eddie accidentally pushes Kate into the Thames, and kills her. A Princess Diana-style mass outpouring of grief follows from legions of besotted believers. Eddie is trolled by death-threatening tweets. The fashion world is in meltdown. And then, like any self-respecting Messiah, Kate is born again, emerging from the deep in her shimmering evening dress, champagne glass in hand, wondering where the party is.

It’s enough to put you off your food. But it probably won’t.