This article is a preview from the Summer 2017 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

What do we mean when we talk about “empire”? We use the narratives of imperialism to describe everything from British and American foreign policy in the Middle East to the rapid global spread of McDonalds and Coca-Cola. But we are less comfortable with discussions that focus on the real legacies of imperialism and draw up a balance sheet of privilege and oppression. European empires had conquered much of the globe by the end of the 19th century, and the relationships they established continue to shape our world today. Yet in Britain, at least, there is instinctively a kind of cringing reaction to bringing the conversation around to empire. Television today is more likely to feature dramas lauding the culture and society of imperialism – Channel Four’s recent offering Indian Summer sits within a long lineage of fictional depictions of imperialists and their struggles – than documentaries exploring imperial brutality in India, in Kenya, in Jamaica. The British people – or at least, perhaps, the white middle classes – seem reluctant to engage with the idea that empire could have been a story more marked by bloodshed than by fraternity.

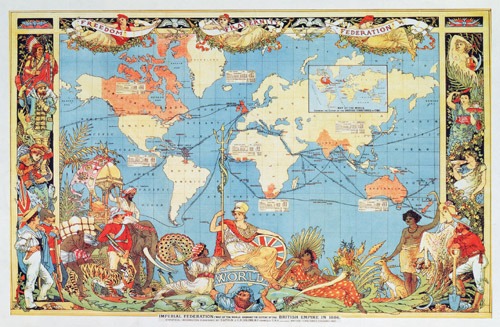

It has become commonplace to ascribe this to a type of “imperial nostalgia”. There was certainly a moment where British pop culture seemed rooted uncritically in the vintage – matte red lipstick and beards, bunting and gin-and-tonics drunk from teacups – with this aesthetic perhaps culminating in street parties celebrating the wedding of Will and Kate in 2011. Six years later, this seems to be playing out in a harder cultural turn. The vote to leave the European Union was framed by many as going “back” to some moment of mythical British power. The paradox of plucky little Britain, standing alone against the bureaucratic monolith of Europe, yet backed up by a vast imperial network (now repackaged as a Commonwealth of equals), pervades politics, media and culture.

What’s being left out of this story? Would a fuller understanding of the past help us to make better decisions in the present? To explore these questions, I spoke to professor Gurminder K Bhambra, a sociologist at the University of Warwick, whose work looks at the ways in which the voices of the colonised and their descendants have been shut out of official narratives. I was interested to see how this compared with my own work as a historian, and I wanted to understand how the presence of empire in British politics – or its forced omission – shapes our experience of the world today.

Charlotte L Riley

Charlotte L Riley: It seems as if, in recent years, there’s been an effort in Britain to talk more about empire – but the conversation is very fragmented. On the one hand, you have these accounts, from the historian Niall Ferguson to film and television dramas, that seek to tell a positive story, while on the other you’ve had campaigns to “decolonise” the university curriculum, or to remove monuments to Victorian imperialists like Cecil Rhodes. And such efforts to challenge the dominant narrative often generate a hostile response. What’s going on here?

Gurminder K Bhambra: I think Europe is the one part of the world that hasn’t actually decolonised. The places that were colonised have gone through a process of understanding that colonial history, but Europe hasn’t taken into account its colonial past, and so it continues to repeat particular patterns, without realising that this past is no longer part of its present. Brexit is absolutely a symbol of that.

CR: So the end of empire is not necessarily a reckoning with or an understanding of the imperial past?

GB: No, and I think European politics is partly responsible for that: the period of decolonisation, in the mid-20th century, merges into the period when Britain is in negotiations to enter Europe. So becoming part of a new transnational federation in a way mitigates against the loss of the colonies. Britain never has to consider that it is no longer a global power, because it’s now got a global status by being part of this larger federation. So in a sense I think that this process that’s happening right now is the ultimate working out of that imperial past, and having to deal with what it would mean to no longer be a part of Europe and also not be a global power.

CR: The idea of Britain using Europe to avoid dealing with its imperial past is really interesting, because it also sets Britain against other imperial metropoles: do France, or the Netherlands, or Belgium also fail to acknowledge their past in a similar way?

GB: When the European Economic Community is established in 1957, France negotiates a special deal for its colonies, which gives them privileged access to Europe. And so because the EEC is established before decolonisation in Africa, it maintains a particular hierarchical relationship through the various treaties. Colleagues of mine, Peo Hansen and Stefan Jonsson, have written about this – see their book Eurafrica (Bloomsbury, 2014), for instance. If decolonisation in Africa had happened before European unity was established, then we would probably have quite a different global order.

CR: In the 1940s, Britain’s initial understanding of how Europe might work after the Second World War was precisely this idea of “Eurafrica”, as a third way between the United States and the Soviet Union – which was in a way modernising and forward-looking, whilst also being rooted in imperial power. Now, there’s the idea that Britain will go back to a type of Commonwealth trading – but the Commonwealth that’s imagined is always a white settler Commonwealth.

GB: It’s CANZUK: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK.

CR: Yes! The MEP Daniel Hannan, who was one of the main architects of the Leave campaign, has as his Twitter header photo this sort of mocked-up flag of CANZUK, which has the Canadian maple leaf and New Zealand and Australian flags mixed with the Union Jack. It’s this explicitly white Commonwealth imaginary view of Britain’s future. Brexit is obviously a way in which this concern with the imperial past has become very contemporary – and I wondered how far you thought that Brexit represents a type of imperial nostalgia.

GB: I think that played a part within the rhetoric in the lead-up to the referendum. There was this strange juxtaposition of two contradictory ideas. On the one hand, there was a visceral anti-immigrant, anti-EU and anti-darker British citizens feeling. It wasn’t just about immigrants or the EU, it was also about British citizens who don’t “look” right according to the people making those types of arguments. At the same time, there was this idea that leaving the EU would enable us to establish our old Commonwealth links, with Leave supporters arguing that it was unfair that EU citizens could come to Britain without any connection to the country but that the grandparents or relatives of people in Britain from the Commonwealth couldn’t do the same. What people didn’t seem to understand is that when Britain was negotiating to enter Europe in the 1970s, it used the argument that entering the EEC would enable it to stop Commonwealth migration – and now apparently we were leaving the EU in order to enable Commonwealth migration. These contradictions do not really stand.

CR: The idea of nostalgia feeds back into this discussion about Britain’s place in the world. There is both an anxiety about Britain’s place now, but also a discomfort among many people in Britain with any argument that the Empire was a bad thing. There is a sense that not only does Britain need to reclaim its “greatness” – which apparently also involves not having pink passport covers any more and all sorts of things – but also that Britain should be able to celebrate aspects of its past that many people might believe are not appropriate to celebrate.

GB: There you see how the contradictions of the rhetoric mirror those in the US, where a narrative about becoming “great again” is also prominent. This argument about going “back” – when are we going back to? Pre-civil rights, pre-equal rights, do you want a period of legalised segregation? Who is it that the narrative of going back appeals to? Certainly not the huge group of people who would have been second-class citizens then. It’s not neutral. Even “imperial nostalgia” seems like quite a nice benign idea, but if we actually think about what empire was, and how it enabled some to live better than others – even if we accept that there were massive differences between the populations in either place – that doesn’t take away from the fact that in some places there were famines that killed 20 million people, and in others there weren’t.

CR: It’s also interesting that this nostalgia apparently imagines a moment in history where Britain was not a multicultural society. Actually, we would have to go back centuries to find a moment when Britain was not multiracial. The 1950s, for instance, were a decade of mass migration from all over the world, building on 200 years of imperial migration, and a much longer legacy of people coming to Britain from Europe and other places. So this imagined picture of Britain created through imperial nostalgia is wilfully ignorant, as well as erasing the experiences of people who aren’t white male elites.

One of the things that really struck me when I was thinking about this topic was some of the recent YouGov polls that have been carried out on empire and imperial memory. In January 2016, there was a YouGov poll that suggested 43 per cent of people in Britain thought empire was a “good thing”, and 44 per cent thought that Britain should be proud of its empire. In the same poll, 59 per cent thought the Cecil Rhodes statue at the University of Oxford should remain where it was. It’s an interesting poll because it deals with questions of empire both in the general and in the specific. People’s reaction to the Rhodes statue as a remnant of empire in Britain depends very strongly on their sense of what the empire actually was.

GB: It also depends on whether you knew what Rhodes had done. At some point, when you come to reckon with your history as a nation, who do you valorise, who do you decide no longer represents who you are? If, at the moment, we still think we are represented by these figures who massacred people, who exploited resources in other places, who were involved in processes of appropriation (which is just a polite term for theft), and that our wealth is based on these processes, what does that say about who we think we are?

CR: Thinking about the Rhodes statues, and other imperial commemorations – Southampton has a General Gordon statue, and students at the University of Bristol have been campaigning to change buildings named after the slave trader Edward Colston – leads us to ask what these things do to our understanding of history. One of the arguments against removing them is that this would be an “erasure” of history, or alternately perhaps whitewashing British history.

GB: We can look at how other nations with conflicted pasts have dealt with contentious elements of their histories. I don’t think that anybody in Germany is able to avoid reckoning with the period of National Socialism, and they do that despite having removed all the memorials, statues and other Nazi insignia. It isn’t clear to me why the statues are needed for a reckoning with this history. In fact, having these statues present has actually led to avoidance; it’s only when campaigners have argued that these statues should either be removed or placed in their proper historical context that debate has been generated. More people know about Rhodes now, as a consequence of the arguments being made by the students behind the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in Oxford, than would have known about him previously. When people say that there is an aspect of censorship, I get really annoyed, because the students aren’t seeking to close down debate, they are interrogating what Britain’s past was really about.

CR: The way that Germany has dealt with the history of National Socialism is interesting because I feel like in many circles that comparison between the British Empire and Nazism would be quite controversial. Many of the people who support the retention of the statue of Rhodes at Oriel College would be horrified if we equated it with preserving a statue of Hitler in the centre of Berlin. And I think that points to Britain’s imagining of its past within a wider context, and what comparisons are seen as legitimate. What other stories do we need to bring into this conversation?

GB: When we talk about empire, we often don’t talk about colonialism. There’s a way in which we speak about empire as a state form that already exists, without talking about the processes that enable empire to come into being. Empires come into existence through genocide – the settler colonies of Canada and Australia are built on the genocide of indigenous peoples. Empires are also built on the dispossession of land from those who remain, and the appropriation of resources from these areas: the wealth flows from the colonies to the metropole and is used to fund future imperial projects.

Up until the late 19th century, over 50 per cent of the revenue of the British government came from the labour and resources of the colonies. People overseas paid tax to the British government that was used to fund the British domestic economy. But the extractive forces of imperialism are now dismissed.

When we think about the present, and arguments that are made during elections – why are people coming over here when we’ve paid into the system for the NHS and they haven’t – well, the overwhelming majority of refugees to Britain come from former colonial territories, and so their ancestors did “pay into” Britain’s economy. If we were to think about the processes that allowed Britain to become an empire we would have to recognise the extent of the violence that was involved, and we would have to think about how we honour those men – and it was largely men – who undertook those expeditions and managed those processes.

CR: The two things that are missing from a popular British view of empire are violence and money. So many people celebrate Britain’s ability to have an empire, with the implication that Britain had an empire because of some sort of innate worth, or natural ability to exploit these “less developed” areas – as seen in Niall Ferguson’s “killer apps” of the Protestant work ethic and the industrial revolution. But these arguments ignore the fact that the industrial revolution, which provided the railways and the machine guns and the medical advances that enabled Britain to establish colonies in Africa and India, was funded itself by imperial violence and the slave trade. There is so little acknowledgement of the scale of violence at every level of empire, from state violence to individual cruelty, which are either glossed over or dismissed as the actions of bad apples. Thinking about empire fundamentally in terms of money and violence also evokes the reparations debate – both in the US and in Europe – and I wondered what you thought about this question of reparations for imperialism.

GB: The only way we are going to move forward is by bringing reparations to the centre of our argument. There is a need for reparative histories, and we need to think about the discipline of history through the lens of reparations; there is no way in which we should be able to write a history of Britain without engaging with these questions of violence and the appropriation of resources. That reparative history should then lead in to a political project for reparations. If we are interested in questions of inequality in the present, we have to think about how inequalities are constituted by these historical processes, nationally and internationally.

CR: It’s telling that newspapers like the Daily Mail, who are unapologetically celebratory of Britain’s imperial history, are also some of the loudest voices against international aid spending. There is a cohesiveness to that position, of promoting Britain’s empire while criticising aid. Actually, international development and humanitarianism is a way for Britain to have a role in the world, albeit a very different role, within fairly problematic structures.

GB: I don’t think that simply changing language is sufficient, but if we were to reconceptualise aid as “reparations”, it would give us a different relationship to these other countries. In many ways, at the moment, we naturalise the idea of poverty, seeing countries as just “poor” while we just happen to be “rich”. If we were to recognise that their poverty is generated by the same processes that created our wealth, and that inequality is generated by historical processes like imperialism, extraction and appropriation, from which we continue to benefit, we could think about how to take responsibility for what we enjoy. It would also take the question of morality out of the narrative and reconceptualise this as justice.

CR: Too often people see aid or inequality within the context of things like charitable giving.

GB: Which makes it all about us – it’s our benevolence, as opposed to us making right the wrongs that we have committed.

CR: It’s interesting how that represents a shift, because in the 1960s politicians like Barbara Castle were quite explicit that international development was about righting the wrongs of colonialism. That has completely shifted now, to the point where, in the 1990s, Claire Short could argue that the Blair government had no relationship to colonialism and that, as many ministers had Irish roots, they were in fact “colonised, not colonisers”.

One of the other things that I find interesting about this is how British people view the world today, their perception of their role in the world and how other places might view Britain. Again in a YouGov poll, in 2014, 49 per cent of people polled said that places colonised by Britain were better off for it. There seems to be a real belief in Britain as a benevolent agent around the world. I wondered how you thought we could address that belief?

GB: On one level it would be about telling the history properly. The places that were colonised – if we’re talking about Africa, in some places they went through a double colonisation. First the populations were stolen and turned into slaves, and made to work in plantations. The areas were depopulated, and European settlers moved in, and there was a second extraction of material resources. We need to situate our understanding of these nations today within that historical context. When Britain first engaged with India, it engaged as a lesser power – the Indian economy was in the top five in the world, and Britain systematically used violence and appropriation to subjugate India. Colonisation did not make India a better place; it is now having to catch up to where it was before Britain occupied it for 200 years.

And, for example, when people talk about Britain developing railways around the world, it didn’t do this for the benefit of others, but to transport materials and commodities for its own purposes. If there was a positive consequence, this was unintended, and what makes us think that other nations wouldn’t have developed these railways themselves anyway? The cotton industry in Britain is another example – it’s central to the industrial revolution, but it isn’t a crop that grows in Europe, let alone in Britain. The technology of how to dye and weave it came from India. All Britain did was mechanise the process. There needs to be a better historical account that brings all these things into a single narrative, rather than having a nationalist lens, which suggests that processes within one set of borders are unconnected to what is happening elsewhere.

CR: I agree that we need a better process of education but these conversations have already been happening for a long time. Perceptions are warped by a sense of racial hierarchy, too. The popular understanding of empire is that Britain moved around the world imparting civilisation to poor savages. There is little understanding of the fact that Britain’s economy could have been less advanced than the Indian economy, for example.

GB: And this idea of Britain having a history of free trade – how can you have an understanding of free trade without taking empire into consideration? For example, China did not wish to trade with Britain, so Britain got the Chinese population hooked on opium and then went to war in order to force China to accept “free trade”. But there is no understanding, within this idea of Britain as a liberal democracy committed to free trade, that free trade can be a violent process in its own terms. It isn’t a neutral process of exchange and market relations among different groups of people. It is having a gun and saying, “You will sell me what I want, at a price I am willing to pay, or I’ll just take it.”

CR: Slavery is an interesting case study within imperial history. In 2007, there was the 200-year commemoration of the end of the slave trade and there was a lot of coverage that celebrated Britain’s role in ending it. This cast Britain as a humanitarian benevolent force that rights the wrongs of other people’s empires, with very little acknowledgement of the fact that the only reason that Britain was in a position to end the slave trade was because Britain was by this point its most prolific agent.

There seems to be deeply engrained within Britain the sense that our empire was better than other empires, and that the British empire was not violent in the sense that the French or Belgian empire was. This builds on a larger idea of British exceptionalism – that Britain is not militaristic like Germany, or does not have the social problems of the US, for example.

We’ve spoken about reparative history and the idea of imperial nostalgia. There is a sense among some people in Britain that they personally did not benefit from empire. Similarly to arguments about ideas like “white privilege”, there is a sense among some that the white working class in Britain did not benefit from empire and should not be forced to apologise for imperialism or acknowledge this history.

GB: I have no interest in people simply apologising for this history. Nobody alive today is directly responsible or should feel guilt for what happened in the past, but we can take responsibility for the processes that privilege some and disadvantage others. There are obviously differences in the extent to which any population benefits straightforwardly from empire. But there has to be a recognition that, for example, during the Second World War when there was the beginning of a famine in Bengal, wheat was removed from Bengal and used to feed British troops as part of the war effort. That led to the death of 3 million Bengalis, not because there wasn’t enough grain in Bengal, but because that grain was taken away and used to feed British troops elsewhere. Those troops may not have been fighting in the best conditions, but they didn’t starve, and others did. And that is a relationship that we have to reckon with.

CR: I think also it’s about trying to draw people’s attention to the structures of empire. Britain did not want to control a quarter of the world’s population because it desperately wanted to spread Christianity or because it really felt that these people need bringing to civilisation. Fundamentally this was an economic and political process. And so much of Britain’s cultural nostalgia for empire, and so many of the echoes of empire in British cultural life, this non-specific longing for a time of bunting and gin-and-tonic and grateful smiling children, is denying the fundamental truth of how empire actually operated.

GB: If it was the friendly collection of nations that most Britons think it was, then why aren’t Commonwealth countries happily agreeing to trade with Britain after Brexit? In fact, they are saying no.

CR: That reminds me that, at the end of the 19th century, there was a reimagining of the empire by British socialists as the Imperial Federation, which would be about fraternity, equality and free trade. That image is present in much of the British language about the empire and the Commonwealth today. But that’s not what anybody else is saying.

GB: Yes, because they have different memories. They have the same history, but they remember it differently.