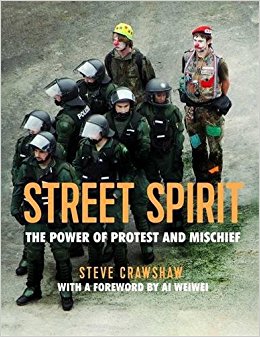

In Britain and the US, we have recently seen a wave of political upheaval - from Brexit to Trump - triggering a series of protests. There is a long, noble tradition of popular protest against repressive regimes, with people taking action against overwhelming odds. In his new book "Street Spirit: The Power of Protest and Mischief", Steve Crawshaw - a human rights advocate with Amnesty International and former foreign correspondent - examines different forms of protest. The book looks at inventiveness and humour in protest, from America's civil rights movement, to the Arab Spring and Ukraine. Here, he discusses the power of small acts of resistance.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I have always been obsessed with the idea of the change that can come and the little stories that get too little notice. I wanted to tease out the meaning of those stories; why it is that real change happens – often there are elements of humour, creative mischief and things like that that create change. I find it incredibly inspiring.

What’s the interplay between small and big acts of resistance?

Of course, every single act – from going to a protest, to going to vote – is part of a bigger whole. Equally each of us thinks: “what can I actually do? Does this really make a difference?” The bigger stories become part of the history books, and seeing the big picture is very important. But I love the humanity that comes through on the individual person who decides to confront a regime with some crazy act – eating sandwiches in Bangkok with the military junta, or pretending to clap against an unloved president in Belarus. All these might be seen as things which can’t make any change at all but we’ve seen that those acts put together can create truly extraordinary change. Again and again, pundits say this can’t go anywhere, it won’t change anything, and then people’s courage and defiant belief in what they might be able to do – not what they knew they would be able to, but what they might be able to – meant things turned out differently.

How should we judge the success of protest movements?

In the short-term, often things don’t seem to be moving at all. The first place I saw utterly amazing things happen was Poland in 1980. I happened to be living there, and at that time there was an extraordinary movement, Solidarity – it was an independent trade union but in some sense it was an opposition movement although it never officially called itself that. All the Western pundits said the demands the strikers were calling for were utterly unthinkable. But a few years later, it came back with a lot of creativity and mischief. You can look at a certain moment and say, we seem to have failed - but those who continue to believe can still create that change.

There are different, fully understandable reasons why people lose hope. One of my heroes, Vaclev Havel, talks about the “power of the powerless” and “living in truth”, which means doing what you know to be right even if you don’t know if you’re actually going to succeed.

There was an incredibly powerful video produced when the protests against Hosni Mubarak in Egypt began in 2011. A young woman, Asma Mahfouz, produced a video in her apartment saying, “if you guys don’t go out because no one else is, then you are just as much a part of the problem as the brutal secret police”. That video went completely viral and helped trigger the massive protests which in turn did bring down Mubarak within just a few weeks. The power of believing that change is achievable is truly remarkable. There are continuing problems in Egypt, but I’d argue that doesn’t detract from what was achieved.

Some argue that nonviolent protest only works when there are other factors at play. Could you expand?

What I saw in Poland during the 1980s was one example where people back-flipped from saying “this is impossible, it will never achieve anything”, to after it was achieved saying “this was obviously going to happen”. It may be obvious in retrospect but they didn’t see it coming, and that’s been true of many things. Even now, you still do hear the argument that you can only really achieve change if the regime is ready to be nice. Very many past examples prove that wrong, including in hard-line Communist places in Eastern Europe and in brutal military dictatorships in Latin America.

A few years ago, there was an interesting book, Why Civil Resistance Works, by two sociologists. The book is packed full of statistics which are very interesting about how using violence to create change means attacking the oppressive regime on its strongest front – they’ve got all the tanks and guns and are most comfortable with that. Secondly you lose support, you’re less likely to have all the population behind you if you’re fighting. One of the most interesting things was that even where change had been created and the repressive government had been overthrown, your chances of stability after creating that change are immeasurably smaller if there has been a lot of violence creating the change. If you’ve managed to use non-violent protest and stick with it, the chances of stability are much greater.

Once that’s been said it’s kind of obvious. You can understand why people grasp for the gun as an act of despair, but look around the world and you can see so many examples where you think: if only.

What do you think is the most effective way of bringing about social change?

Above all, I think belief is what matters. When belief stops, you don’t do things. As regards techniques, there’s so many I’d almost not know where to start. Creativity and humour is incredibly important for sustaining things. It makes it fun to observe and to be part of. Even in the darkest times, creativity and humour are important.

Knowing what you want is also really important. It’s obvious, but if you’re saying “I don’t like this” but you don’t know where you want to take it, it’s less likely to have impact – especially when dealing with really big issues.

It’s vital to realise that you need to focus on the main thing that you want to change, whether it’s say, overthrowing Hosni Mubarak or the Serb ruler Slobodan Milosevic. You want to bring together as many people as possible. There’ll be time for argument about how to move forward after the big change has happened. If you start being sectarian while seeking the big change, you end up fragmented and the chances for change are much smaller.

What impact has social media had on protest?

It is endlessly discussed, often in a fairly sterile way, that we live in a world where social media clearly has meaning way beyond anything thinkable even a decade ago. But it’s not that things like Facebook and Twitter have utterly changed the world of protest. The civil rights movement in the US or the great Eastern European protests in the 1980s happened in powerful and networked ways, before those modern forms of communication existed. But equally the fact that they do exist opens up incredible possibilities. Knowing what people are thinking about – which is so much easier than in the old days when you had to talk to people to find that. Also knowing what is happening elsewhere. There might be a protest in a town 20 miles away but if it’s not on the news you might not know. That sense of knowledge gives power and strength to any protest movement.

Your book focuses on mischief in protest. Are there common ways that this manifests around the world?

To some extent there are common themes; there’s mockery of regimes in different ways which puts the boot on the other foot. You see echoes – sometimes acknowledged, sometimes not.

One great example was in Poland. They had this wonderful approach, at a time with Solidarity was banned and it seemed things weren’t going to change at all in Poland as in so many other countries where an oppressive regime doesn’t want the truth to be spoken, people painted political graffiti. Protesters in Poland subverted this narrative. Instead of painting political graffiti, a group painted what in Polish are called “little red hatted folk”, dwarves or gnomes, onto the walls. They became the emblem of resistance in an odd, oblique, witty way. You didn’t know quite why these gnomes were illegal but the state knew something was wrong. My favourite quote was a police message saying “you must arrest all the gnomes!” when people had gone on a protest dressed up. Stories like that can sound fun, but what do they change? That particular demonstration came just as key talks started a few months later, which basically led to almost democratic Polish elections in 1989, a non-Communist Prime Minister, and a few months after that, the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Another example is from Thailand, where the military junta was forbidding a whole range of actions, especially public gatherings. The way people began to subvert that was simply to have “a picnic”. You ended up with the faint absurdity of people being arrested literally for eating sandwiches in the park. It made the military junta look completely ridiculous by the fact that it didn’t even dare tolerate people eating sandwiches. That put the spotlight onto the craziness of the regime itself.

Britain is in a period of upheaval. Do you think we’ll see more protest?

We now live in a world where on both sides of the Atlantic we’ve seen that protest has become massively important in many different ways, and it will continue to be extremely important in creating change for sure. I think one of the things we’ve seen in recent months in the UK is the importance of not letting anyone else tell you what can or cannot be achieved. Even voting is a kind of statement where each individual can feel their vote isn’t going to make much difference. In Britain the pundits got completely and utterly wrong the direction recent votes would go, because more people who cared passionately about the need for change went out and demanded that change at the ballot box than anybody expected. I think that’s a reminder to us on a whole range of issues of how much it matters.

The phrase that Havel used of living in truth is something all of us should be thinking about. It was coined in the context of repressive regimes but it’s important for all of us to think of it in our daily lives. In a world where there are some people who think that hatred between religions, especially demonising the other, is a normal way to go forward, it needs everybody to stand up and speak for that common sense in order to make sure the humanity we all need will continue. We are confronting a huge challenge of some politicians who believe they can press certain buttons in order to encourage hatred. Each of us needs to stand up strongly and confront that. It goes back to the same thing, knowing that we can create a positive direction – if enough of us use our voice.