This article is a preview from the Winter 2017 edition of New Humanist.

I’m only too aware of the multiple meanings aroused by the phrase “a good sense of humour”. It’s not that long ago, after all, since the time when a corpulent male executive would advertise for a “Girl Friday with a GSOH” when what he really required was someone who could be counted upon to smile delicately at his ponderous double entendres and uncomplainingly accept a bit of slap and tickle in the photocopying room.

But, despite such ambiguities, I still like to feel I have the edge on most of my friends and colleagues when it comes to finding humour in even the tensest of situations. Only last week I had all four of the assistants in my local Vietnamese nail bar rocking with laughter when I told them about the man who’d decided not to propose to his girlfriend at the ice skating rink because he’d get cold feet. (I should explain that I was only at the nail bar because my toenails have lost their genetically prescribed sense of direction and begun to grow inwards rather than outwards. And I should add that I only opted to have my toes attended to after the male manicurist had assured me that neither he nor anyone else in the Prince of Nails salon had been kidnapped and forced into a life of service.) I can also count my dentist among my fans. He and his assistant loved my pre-operative implant joke about the Buddhist who overcame his fear of dentistry through transcendental medication so much that they had it framed and placed on the wall in the reception area.

I’ve had much the same success in legal settings. My old divorce solicitor, Gerald Knightley from Stoke Poges (someone in the know advised me that out-of-town lawyers are always cheaper), particularly relished my story about the solicitor who asked a friend why people took an instant dislike to him when they found out he was a lawyer. “It saves time,” his friend had explained.

All these successes have only made me more aware than I might be otherwise of my failure to elicit even so much as a mild smile from my doctor. A couple of years ago when I popped in for my annual flu injection, he took advantage of my rolled-up sleeve to test my blood pressure. “Not so good,” he murmured, as the cuff wearily deflated. “We’ll need to keep an eye on that. It might be nothing more than white coat syndrome; some people’s blood pressure goes up at the mere sight of a doctor. But if we fit you up with an ambulatory device, which checks your pressure every 30 minutes as you go about your daily business, we should have a better picture.”

“That reminds me,” I said – sensing the tension in the air as I packed away the ambulatory cuff and monitor – “of the two doctors on a picnic. One of them lowers his picnic cup from his mouth and says resignedly, ‘You know, the experts are spot-on. It is thicker than water’.”

My doctor’s singular lack of response to that joke was still weighing on my mind when I turned up last Tuesday for my annual all-over medical examination. But as the examination concluded, something even more pressing demanded my attention.

“You can slip your trousers on again,” he said as he noticed that I was still standing before his desk with my pants around my ankles.

“Haven’t you forgotten something?” I said.

“Forgotten something?”

“The old prostate,” I said.

“What about the old prostate?” he asked, adjusting his AstraZeneca calendar so as to improve the sight line.

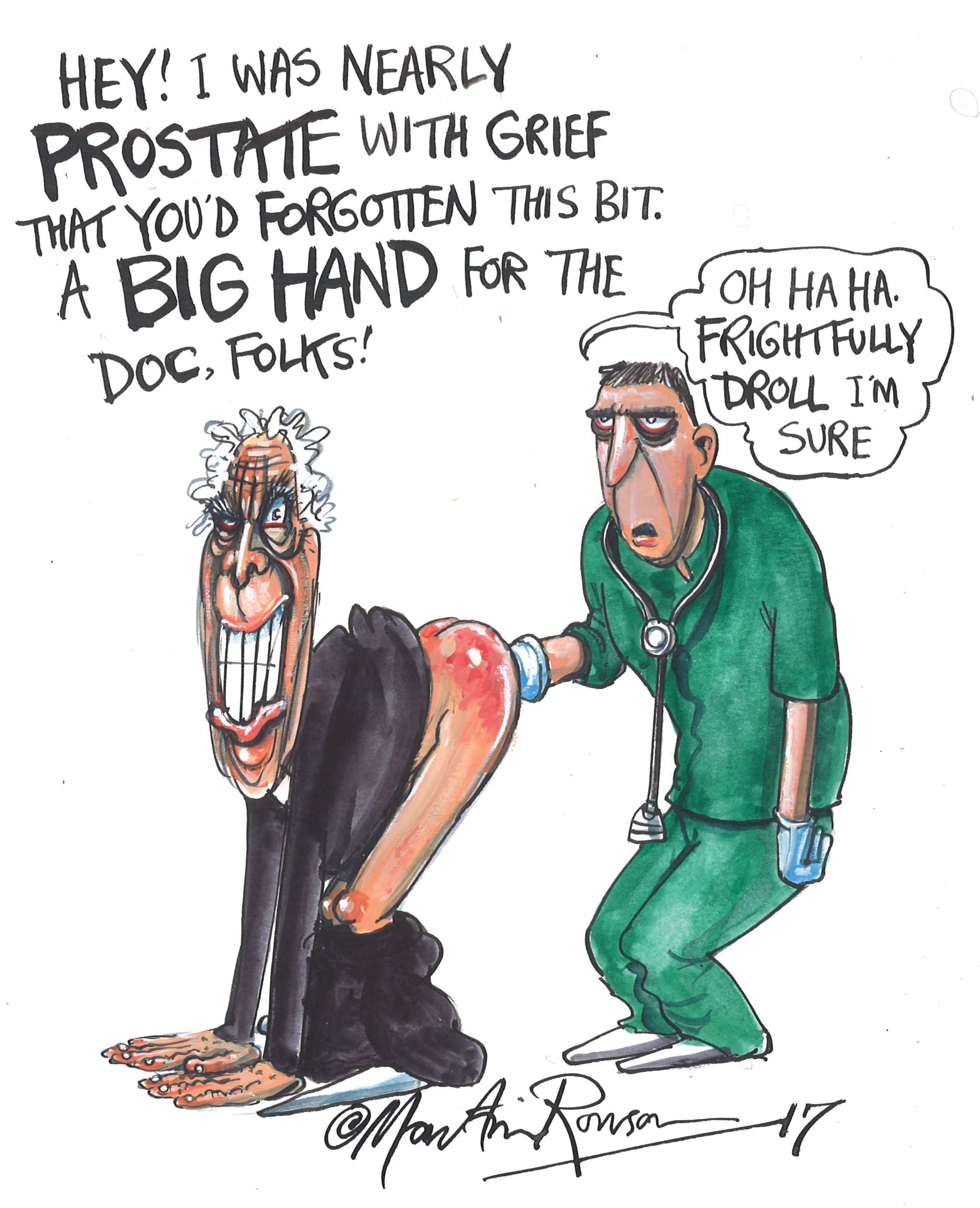

“You didn’t do your usual rectal insertion,” I stuttered. “You didn’t do the usual thing. You know. You didn’t … you didn’t put your finger up my bottom to test my prostate.”

“Well, we do that now by simply checking your blood sample for elevated PSA,” he explained. “Bottoms, as you choose to call them, don’t come into to it any more. Sorry if that’s some sort of disappointment.”

It was only as I walked through the crowded waiting room that I realised I could have dissipated some of that surgery awkwardness with one of my little jokes. I could have reminded my doctor of the unfortunate butcher who sat on his bacon slicer and got behind in his work. Next time perhaps.