This article is a preview from the Autumn 2018 edition of New Humanist

Barracoon: The Story of the Last Slave (HQ) by Zora Neale Hurston

“Of the millions transported from Africa to the Americas, only one man is left,” Hurston writes in Barracoon. Her task, in this rediscovered 1930s masterpiece of literary journalism, was to record his life.

While Britain celebrates having outlawed the slave trade (though not, at that point, slavery) in 1807, it is estimated that a quarter of all enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas after then. Kossola – later named Cudjo Lewis – was one of them, and he arrived in Alabama on a covert slave ship called the Clotilda, at some point in 1860.

Hurston – a writer, ethnographer and prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance – met him over 60 years later and interviewed him several times. She would bring peaches, watermelon and ham in the hope that he would feel like talking that afternoon. Sometimes he didn’t say much, or told Hurston to leave him in peace, but other days he was warm and narrated his life in great detail.

Kossola lived in west Africa until he was 19, and recalls his desire to find a wife and start a family. That was before a raid by Dahomey warriors. His description of the massacre is difficult to read: women and older people were decapitated, and their heads attached to the belts of their attackers; the young and fit, Kossola among them, were tied together and marched for several days towards the Atlantic Ocean.

Perhaps surprisingly, there is little detail of the slave trade itself in Kossola’s account. Unlike Saidiya Hartman’s influential history Lose Your Mother, we do not get a vivid description of his time waiting, in chains, to board the ship. Nor are many pages committed to the voyage along the Middle Passage – and even Kossola’s descriptions of slavery are cursory. Indeed, Kossola only spent five and a half years living as an enslaved man; he spent many more living in postbellum Alabama.

Crucially, however, he was a man who came of age in Africa, while many other former slaves had been born in America or only had distant memories of their former homes. This is what makes his account so unique and so different from the testimonies of people like Frederick Douglass, Olaudah Equiano or Sojourner Truth. Kossola’s story is not one of self-realisation and emancipation, it is one of protracted loneliness and disorientation.

Upon emancipation, Kossola and the others from the Clotilda realised they could not afford a ticket home, and so they worked, saved and built something for themselves in Alabama.

They called their village “African Town”. Kossola married Seely, a woman who had travelled with him from Africa, and they went on to have six children. They gave their children African names and American ones, but growing up they were mocked and called “savages” by the other “coloured” children in Mobile, Alabama.

Kossola’s family brought him great joy, but four of his children died young and in tragic circumstances. Outliving his children – and later, his wife – only deepened his loneliness.

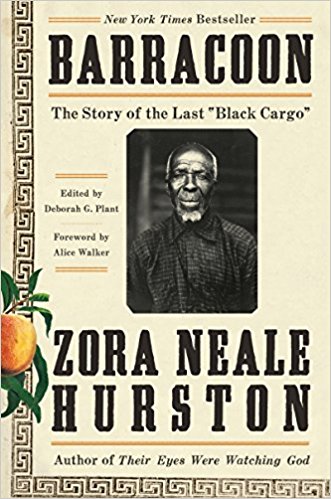

In one of their final interviews, Hurston asks if it is OK to photograph him: “When he came out I saw that he had put on his best suit but removed his shoes. ‘I want to look lak I in Affica, cause dat where I want to be,’ he explained. He also asked to be photographed in the cemetery among the graves of his family.”

Hurston allows Kossola to “tell his story in his own way without the intrusion of interpretation”, but her short descriptions – of his silences, expressions and idiosyncrasies – convey so much. The book is often most affecting in its subtlety. Not in the descriptions of decapitations, nor of the Middle Passage, but in Kossola’s repeated phrase “in de Afficky soil”, which he returns to so often, insistently, as he tries to convey what has been lost.

Hurston did not live to see Barracoon in book form because previous publishers requested that she translate Kossola’s dialect into plain English, which she refused. This refusal is a mark of her respect for Kossola and his way of telling, a recognition that suffuses the book. He liked Hurston and he hoped that his story would travel home: “I wante tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, Yeah, I know Kossola.”

Unfortunately, there was no one in “Afficky soil” who heard his call, no one to say “Yeah, I know Kossola”. If it is true that he was the last man alive transported from Africa to the Americas, then this precious book should be read as a eulogy for all those who were taken – over 10 million of them – and who lived and died far from home.

When reading Barracoon today, the challenge is to move from the worlds Kossola narrates to our own. Criminalisation and mass incarceration the US, structural violence in the Caribbean and Latin America, and police brutality and the Windrush scandal in the UK all remind us that our present is distorted by slavery’s afterlives. Barracoon is one man’s story, but it captures the brutality of the racial ordering which continues to define our present.