Why do we sleep?

How much time have you got? The truth is that sleep has multiple functions, and the functions of sleep change through life. For example, dreaming sleep occupies about a third of the 24 hour period when we are inside the womb, whereas when we are older, it probably occupies about 10 to 15% of all of our sleep time. So clearly REM sleep has an important function in the developing brain. But we also know that if you abolish REM sleep in in adulthood, it doesn't seem to have any major long term consequences as far as we can clearly ascertain. So something that is fundamentally important to the development of our brain in childhood or even in the foetus, probably doesn't have the same function in all of life.

We also know that sleep has important functions in terms of restoration, both for the brain and the body. So for example, in deep sleep, we know that there are channels that within the brain called the glymphatic system that increase in size and flow. We think that one of their functions is to cleanse the brain of toxins that have accumulated over the course of the day. There are other housekeeping activities that occur within the brain that are responsible for memory, learning, forging connections between different parts of the brain. For healing, growth, regulation of metabolic systems - there's a very wide range of functions that sleep has.

Are we getting enough sleep?

The view that we need seven or eight hours, I think, is a good rule of thumb. But there is a discrepancy between the science that is done in the lab and the real world. In the scientific laboratory, we are very, very careful to identify particular groups of people. But actually, for most people, the quality and quantity of their sleep is a function of multiple factors. If there is something biological going on, that influences their sleep – their general medical state, if they're on medication, or have other health issues. But also their psychological state, their behaviours around sleep, and the environment. It's very rare to see somebody with sleep issues purely driven by one thing. What we're doing is extrapolating from scientific studies into the greater population. So the view that we need between seven or eight hours for the general population, I think that's probably about right. But what each individual has a slightly different sleep requirement. That is largely defined by their genes, but also if there's anything else going on around their sleep. People ask me “how much sleep do I need?” The answer is really: you need enough sleep so that you wake up feeling relatively refreshed, and that you're able to stay awake and feel awake throughout the day, and be tired enough to go to sleep at the same time. So if you are waking up at the same time, going to sleep at the same time, roughly every day, and you generally feel pretty good and alert during the day, then that's the right amount of sleep for you.

Are we sleeping worse than we did in the past?

If you look at the average duration of sleep 50 or 60 years ago, as a society we are definitely sleeping less than before. That certainly implies that our sleep has deteriorated. I'm sure that the way that our society is currently structured is conducive to a significant proportion of us being slightly sleep deprived. But I think it's probably a more complex picture – 60 or 70 years ago we were sleeping in unheated houses, in uncomfortable beds, and so some of it may be to do with the fact that we're sleeping better than we used to.

You mentioned the difference between the lab setting and the general population. Is the evidence base poor for the assumptions we make around sleep?

One of the big things is the confusion between sleep deprivation and insomnia - not in the scientific literature, but in terms of how the science is portrayed more widely. What we know is that that insomnia does not equate to sleep deprivation. If you are sleep deprived, you'll be very sleepy during the day, whereas actually most insomniacs are not sleeping during the day. In fact, if you give them the opportunity to fall asleep during the day, they won't. Insomnia is the subjective experience of having either too little sleep, poor quality sleep or disrupted sleep. Subjective experience often correlates poorly with objective measures of sleep. Some people who complain bitterly that they haven't slept at all actually, when you bring them into the sleep lab and record their sleep, they will sleep seven hours overnight. When you bring them in to discuss the sleep study they will say, "I got one hours sleep", and then you pull up their sleep study and you see that actually, they've had a fantastic night sleep - probably better than I've had. It's quite rare, but occasionally we see it the other way around. People will say, “I slept for ages" and then you look at their sleep study and see that their sleep is horrendous. On many levels, equating insomnia with the health risks associated with sleep deprivation is incorrect.

In that kind of scenario, when someone thinks they're sleep deprived but they’re not, how can you treat it?

It is commonly seen in people who have psychological issues. Sometimes we see that people wake up very, very briefly throughout the night, and the conscious brain is perceiving the time between those awakenings as being awake for the whole period. For example, I might see somebody who says, "I was awake from 2am until 5.30am". When you look at their sleep study, you see that they woke up very briefly for about 30 seconds, a minute at 2am. And then again, at 5.30am, but in between, they had two hours of very deep sleep. Sometimes it's a case of addressing psychological or psychiatric issues, be that with medication or non-drug based treatments. Sometimes it is to do with trying to identify the course for those very brief awakenings to try and address those.

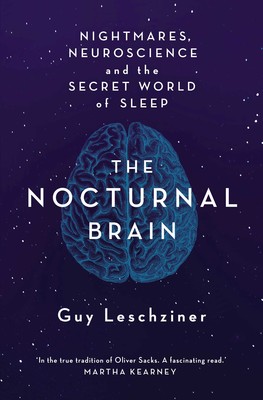

Your book deals with some incredibly eye catching examples of extreme sleep disorders. How did you decide which to include?

I was very keen to write about patients who would be involved in the process of writing about their case. I think that one of the big issues with lots of medical books written for the general public is that the cases are very heavily anonymised. That's for very good reason, but I think it loses something in the anonymisation - it's very difficult to provide a level of detail and to hear the patient's own voice.

How common are sleep disorders?

Some of the conditions that I described are incredibly common. Insomnia affects 30 per cent of adults in any one year. Ten per cent of adults have chronic insomnia, which is a huge number. Sleep apnea affects somewhere between five and 10 per cent of adult men. Restless leg syndrome affects about 5 per cent of the adult population. At the other extreme are the very rare cases like the woman who I write about who drives in her sleep. The condition itself, non-REM parasomnia, is actually quite common – it affects between one and two per cent of the population – but to have it to such an extreme is very unusual

Sleep is often described as a “growth industry”, with the increasing popularity of things like sleep trackers and so on. I wonder what you make of that trend.

Sleep is fundamental to all aspects of our lives, our psychological health, physical health, our neurological health. Historically we've been very poor at prioritising sleep; it is ultimately seen as the bit that you have to undertake in order to get on with the rest of your life. And so this this move in society to value sleep is incredibly important. That said, I am slightly cynical about certain aspects of recent developments – I think that there is a move towards the monetisation and metrification of sleep. In the same way as people measure their lives by metrics, like how much they earn, or how many Instagram followers they have, there is a degree of competitiveness about sleep and almost a moralising around sleep that I think is unhealthy. It causes people to become anxious about their sleep when actually they probably have no reason to be anxious. People are using these sleep trackers which don't track sleep terribly accurately and are drawing conclusions based on incomplete, probably inaccurate data.

The other issue I have with sleep trackers is if you feel tired, or you feel that your sleep is not good, it goes back to sleep being a subjective experience. People who have issues with their sleep know they've got issues with their sleep. The people who sleep well and don't have any major issues but who are buying sleep trackers – the danger is that they become anxious about their sleep, and actually create problems that weren’t there in the first place. I've seen a number of people who've had some issues with their sleep, and then they've heard something about how dreadful lack of sleep is for your health, and their anxiety has increased so much that they have been left with terrible insomnia. It is a double edged sword. On the whole the attempt to understand sleep is hugely welcome. But there are some negative consequences.

How much is there left that we don't understand about sleep?

We are only scratching the surface at the moment. There are a number of particular issues. The first is that currently doing sleep studies is costly, so to do them on a very large scale is difficult. When we're undertaking scientific studies, you're largely basing the phenotype – the category of patient – on what patients tell us rather than more objective measures, particularly when these studies are done on a very large scale. To perform a sleep study on everybody is so expensive. Mostly studies are only done for one night, so we only get a snapshot of their sleep in a lab setting - which may not be representative of what their sleep is normally like. The second issue is that a sleep study only really tells us what's going on in the surface of the brain. The EEG, the tool that we use to stage sleep, only tells us about what's going on in the cerebral cortex. Even then it's fairly limited so we don't really know what's going on under the hood. There are lots and lots of things that we just don't know that remain to be discovered.