This article is a preview from the Summer 2019 edition of New Humanist

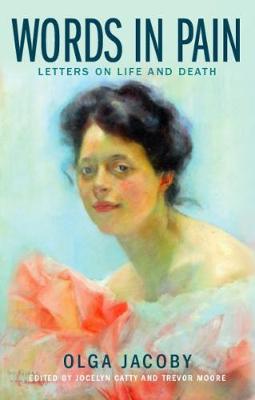

Words in Pain: Letters on Life and Death (Skyscraper) by Olga Jacoby

In comparison with other schools of thought, 19th and 20th century humanism was well-off for women. From Mary Shelley to Harriet Mill to Millicent Garrett Fawcett to Margaret Knight to Barbara Wootton, their writings and speeches form a vital part of any non-religious canon.

Still, the voices of women are not as prominent as men’s and they are not as diverse as the range of men’s. This is why this volume is such a treasure. The letters of Olga Jacoby were first published in 1919 – when the Times Literary Supplement praised them for their “clear-eyed and exalted spirit” – and are now republished in a centenary edition. The letters allow us to excavate the views of a woman who came from a generation of humanist women whose social, political, and philosophical opinions are largely unknown, both because they were women and because, as in Jacoby’s case, they confined themselves – or were confined – largely to the domestic sphere.

Jacoby wrote knowing that she was terminally ill with a heart condition. Her letters begin in 1909 and end just prior to her death by suicide in 1913 aged 38. Written mainly to her conservative and Christian doctor, their chief theme is the questioning of his religion and the advocacy of her liberalism and of her recently acquired humanist commitments.

Her case against her doctor’s religion is simple: the moral turpitude of the “narrow-minded, revengeful, and cruel” God of the Bible, who expects faith with no evidence and makes people suffer – and the damaging consequences of faith itself. A child of Jewish heritage but with little religious knowledge, she encounters the character of God with no previous experience and is an interesting case study in the assertion that, if religion were not taught to them as children, adults would not believe it.

Much of Jacoby’s critique of Christianity is now standard and, for us, is rather tired. The chief interest of her letters is as a period piece. In this respect, their points of interest are almost endless.Take, for example, her tone. The demolition of her doctor’s religion is done with a frankness which feels blunt if not rude to a generation such as ours where honest, robust and heartfelt debate has become rare in public. Her beliefs too seem archaic: teleological in the sense that Nature with a capital N is moving things towards an end, a naive trope of rationalists in the 19th century who could not quite escape the appeal of Providence.

Jacoby is a rather ordinary family woman and although this work should be seen as a rare bloom, which we are lucky to have preserved, it can also be seen as typical of the flowering of a middle-class common-sense humanism which was to be destroyed by the First World War.

“Truth and courage are growing to be the gods of the future,” says Jacoby in one of her letters. A hundred years later, we may doubt that, but we can see why Edwardians may have thought it true, and wonder what the world would have been like had it proved so.