This article is a preview from the Summer 2019 edition of New Humanist

In our liberal democracies, a plethora of radical disagreements are emerging: religious, secular, conservative, liberal, all leading to a fierce debate, polarising and splintering our communities. The fault lines are deep, and the fractures often relate to people’s identities and how they see themselves.

Social media has exploited these differences and accentuated a climate of deep polarisation. Initially it was possible to think that some of these technological breakthroughs would mitigate our troubled relationships. Social media companies promised new forms of community and unprecedented connectedness, and yet people apparently feel more isolated and purposeless than ever before. These fault lines are difficult to repair and reveal deep resentment, but the voting outcomes they produce may not protect people’s best interests. The disaffection is so deep that perhaps there is satisfaction in delivering a “slap in the face” to vested interests by voting for populist outcomes.

Apart from the poor who voted for this new populism, its most obvious victims are the vulnerable migrants and displaced persons, at home and abroad. These victims share one telling similarity. They are weak and they are strangers. Either migrants to our borders, or strangers to be attacked in their own countries: Iran, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan.

One possible remedy, familiar in the time of Homer nearly 3,000 years ago, is a return to a culture of generosity – hospitality to strangers and visitors and refugees. In Homer’s Greek, this is termed a culture of xenia.

In the introduction to her recent translation of The Odyssey (published in 2018 by W. W. Norton), Emily Wilson explains the Homeric concept of xenia: “approaching the island of the Cyclopes, Odysseus tells his men that he has to find out whether the inhabitants are ‘lawless aggressors’, or people who welcome strangers . . . the willingness to welcome strangers is figured enough, in itself, to guarantee that a person or culture can be counted as law-abiding and ‘civilised’.” What has happened to our culture that strangers to our shores are not welcomed? Was it always thus or is there something in our contemporary culture that has lost its spirit of generosity?

Wilson elaborates: “what is distinctive about the customs surrounding hospitality . . . is that hospitality is understood to create a bond of ‘guest friendship’ between … households that will continue into future generations.” Today, we need more than ever to revive some version of xenia if we are ourselves to remain even half-way decent and “civilised”. Xenia embodies what is often called “the rule of rescue” – that those in need of protection, because they are drowning, literally or figuratively, because they need food, shelter, care, medicine or comfort, are absolutely entitled to that rescue, if it is humanly possible to deliver it.

Of course we have not failed to notice that Homer remains a man of his time, and his time is the Bronze Age, around 750 BCE. His moral community in The Odyssey is principally one made up of men of a certain class and status, and the gods. Women only approach equal status when they are either gods or demi-gods, or are important to gods or to those status-secure men. Slaves, male and female, abound, and are in another class altogether.

People have always prioritised kinship bonds – friends and family, tribe and clan, fellow citizens. The moral leap made so many centuries BCE ago, and of which we, shamefully, need to remind ourselves today, is the extension of such bonds to strangers, even strangers of unknown or doubtful class, status or character.

* * *

Our natural proclivity is to privilege “in-groups” – that is, groups we see as similar to ourselves – and at the same time dehumanise “out-groups”, those we see as different. Many will argue that deep within our historical evolution there is a propensity to favour members of our own group and fear the members of another. While it is not unexpected that communities, groups and individuals will wish to stay within their comfort zones and avoid difference, we humans can – and frequently do – reject or overcome dysfunctional or immoral promptings that may arise partially in our evolutionary heritage.

The failure to engage with groups different to ourselves may increase the probability of seeing them as a threat or as the enemy, and thereby stimulate the conditions for conflict. The very act of creating siloed communities in which we do not engage with those who are different to ourselves may feel like self-protection, but can ultimately cause deep divisions. It would be better to find a more empathetic approach – exposure and engagement with the other has the possibility of reducing these fears.

Our creativity offers us the potential to develop antidotes, to mitigate the conditions in which we become suspicious and fearful of one another. Without this contact, we are prone to projection, a psychological term describing how we “dump” characteristcs and traits present in ourselves onto the other. This behaviour increases the level of anxiety and fear within our communities, particularly when there are already tensions. It creates behaviour in which we isolate ourselves from those who we have decided are not familiar, and who behave in a way that we do not like.

* * *

Of course, we have wonderful accounts of valiant hospitality and generosity of spirit. In two very different accounts of xenia in our own times, the authors Eric Newby and Iris Origo tell stories of the kindness of ordinary Italians towards escaping allied servicemen and refugees in Italy in the Second World War. Newby was a beneficiary of xenia while Origo, an Italian by marriage and country of adoption, was one of its most selfless and courageous practitioners.

In his preface to Love and War in the Apennines (Picador, 1983) Newby wrote an account of his experiences as a soldier, prisoner of war and escapee in Italy:

I finally decided to write this book because I felt that comparatively little had been written about the ordinary Italian people who helped prisoners of war at great personal risk and without thought of personal gain, purely out of kindness of heart.

Origo, in War in Val d’Orcia (Allison and Busby, 1999), gives similar personal testimony:

Of the 70,000 Allied p.o.w.s at large in Italy on September 8th 1943, nearly half escaped, either crossing the frontier to Switzerland or France, or eventually re-joining their own troops in Italy; and each one of these escapes implies the complicity of a long chain of humble, courageous helpers throughout the length of the country. ‘I can only say,’ wrote General O’Connor to me, ‘that the Italian peasants and others behind the line were magnificent. They could not have done more for us. They hid us, gave us money, clothes and food – all the time taking tremendous risks . . . We English owe a great debt of gratitude to those Italians whose help alone made it possible for us to live, and finally to escape.’

For a short time all men returned to the most primitive traditions of ungrudging hospitality, uncalculating brotherhood. At most, some old peasant-woman, whose son was a prisoner in a far-away camp in India or Australia, might say – as she prepared a bowl of soup or made the bed for a foreigner in her house – ‘perhaps someone will do the same for my boy’.

This testimony reflects the value of life, telling us that we value it and, to an extent, how much we value it. It also tells us whether we are “lawless aggressors” or people who welcome and protect strangers as well as our own folk. They tell us the extent to which we are truly “civilised”.

The current UK government’s attitude to refugee children fleeing war does not suggest any generosity of spirit. In 1938, in the spirit of xenia, Britain took in 10,000 unaccompanied child refugees from Europe fleeing Nazi persecution, now known as the Kindertransport children. Eighty years later, Europe is dealing with the aftermath of its worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.

Today, Lord Alf Dubs, himself a child of the Kindertransport, is one of the architects of a policy which requires ministers to relocate and support unaccompanied refugee children from Europe and give sanctuary to 3,000 unaccompanied minors fleeing war zones. So far the government has only reached half these numbers. Barbara Winton is co-organising the campaign in memory of the work of her father Nicolas Winton, who organised the safe passage of the Kindertransport children. She wishes to remind us that “a new generation of child refugees have arrived on our continent’s shores only to wait for years in makeshift camps, or risk their lives in the hands of traffickers and smugglers”.

We should call on the government to live up to the Kindertransport legacy by establishing a lasting route of protection for child refugees in conflict zones across the world. But we as individuals can also find spaces around common tables, both within our homes and in the community. The act of breaking bread and sitting together could provide engagement with people who think differently to ourselves. Such practices are the antithesis of a mean-spirited culture where we remain isolated and fearful of the other.

So if we naturally engage with groups who are essentially within our circle of family and friends, how can we extend the spirit of xenia towards people from Syria and Afghanistan? Can we break bread with them, and create a culture of shared stories, in which we understand the lives of people different to ourselves?

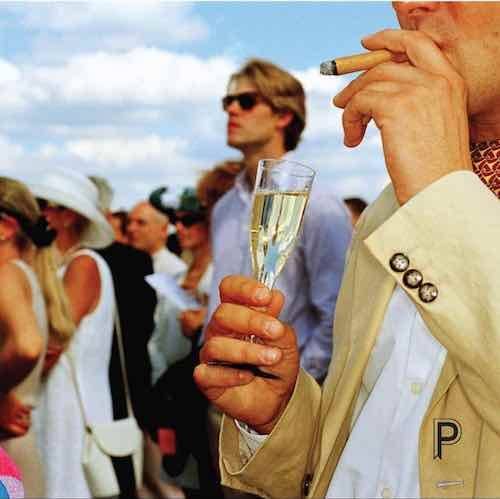

Many of us may need to remember that only one or two generations ago our own families were refugees. Are we prepared to evoke our own histories or do we prefer to retreat behind our walled communities of affluence? It is only by crossing this border that we are likely to humanise these relationships, and weaken some of the current polarised discourse.

* * *

Attempts to adopt the notion of xenia flourish when discontent is not too near the surface. At present we are struggling with a deep sense of fracture; lacking meaningful attachments, people find a perverse bond in hostility towards a common enemy. The outsider becomes the target in a society in which people are already struggling with their own sense of belonging. A toxic environment is created where we know what we are against as opposed to what we are for.

Surely it is what we all share – our common humanity – that gives us hope and connects us in spite of a deep sense of fragmentation. The times when we act socially and co-operatively are when we are truly human: talking, laughing, sharing food, shelter and work. Being alive and surviving together. Xenia is how we demonstrate and reinforce what we are like and learn what others are like. This can only happen in the context of real human contact which gives richness and meaning.

We all have this capacity; our humanity is beyond and prior to our politics. Emily Wilson ends her introduction to The Odyssey by inviting us to be more open-minded. The outcome of doing so may not be what we expect. In fact, in opening our doors, we may well overcome our prejudices and find a forgotten and deep human connection. So listen to her translation of the story of Odysseus as a parable about our relationship with strangers on our doorstep. It generates wonderful food for thought:

There is a stranger outside your house. He is old, ragged and dirty. He is tired. He has been wandering, homeless, for a long time, perhaps many years. Invite him inside. You do not know his name. He may be a thief. He may be a murderer. He may be a god. He may remind you of your husband, your father or yourself. Do not ask questions. Wait. Let him sit on a comfortable chair and warm himself beside your fire. Bring him some food, the best you have, and a cup of wine. Let him eat and drink until he is satisfied. Be patient. When he is finished he will tell his story. Listen carefully. It may not be as you expect.

Are we going to live in a world of xenia or xenophobia? Could the cooking smells of cumin, cardamom, saffron and turmeric create a common table, crossing cultural divides and warring divisions? Reminding us that somewhere a mother is preparing a bowl of soup or making the bed for a foreigner in her house, and saying: “perhaps someone will do the same for my boy.” λ