This article is a preview from the Autumn 2019 edition of New Humanist

When it comes to the march of the machines, it can often seem as if fearful suspicion is the only response on the table. Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror makes such popular TV because it plays on our fears of technological progress, each episode imagining an aspect of our lives fast-forwarded into the near future with reliably alarming results. While tech dystopias fill our screens, one of the most debated books of the year is Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, describing a new all-pervasive reality in which our smallest actions are being controlled and our data farmed in the pursuit of profit. It’s only the latest in a recent spate of bleak books, notably Team Human by Douglas Rushkoff and James Bridle’s The New Dark Age (discussed by David Nowell Smith in the Summer 2019 New Humanist) which argue, one way or another, that our new reality is endangering the progress of humanity, rather than advancing it.

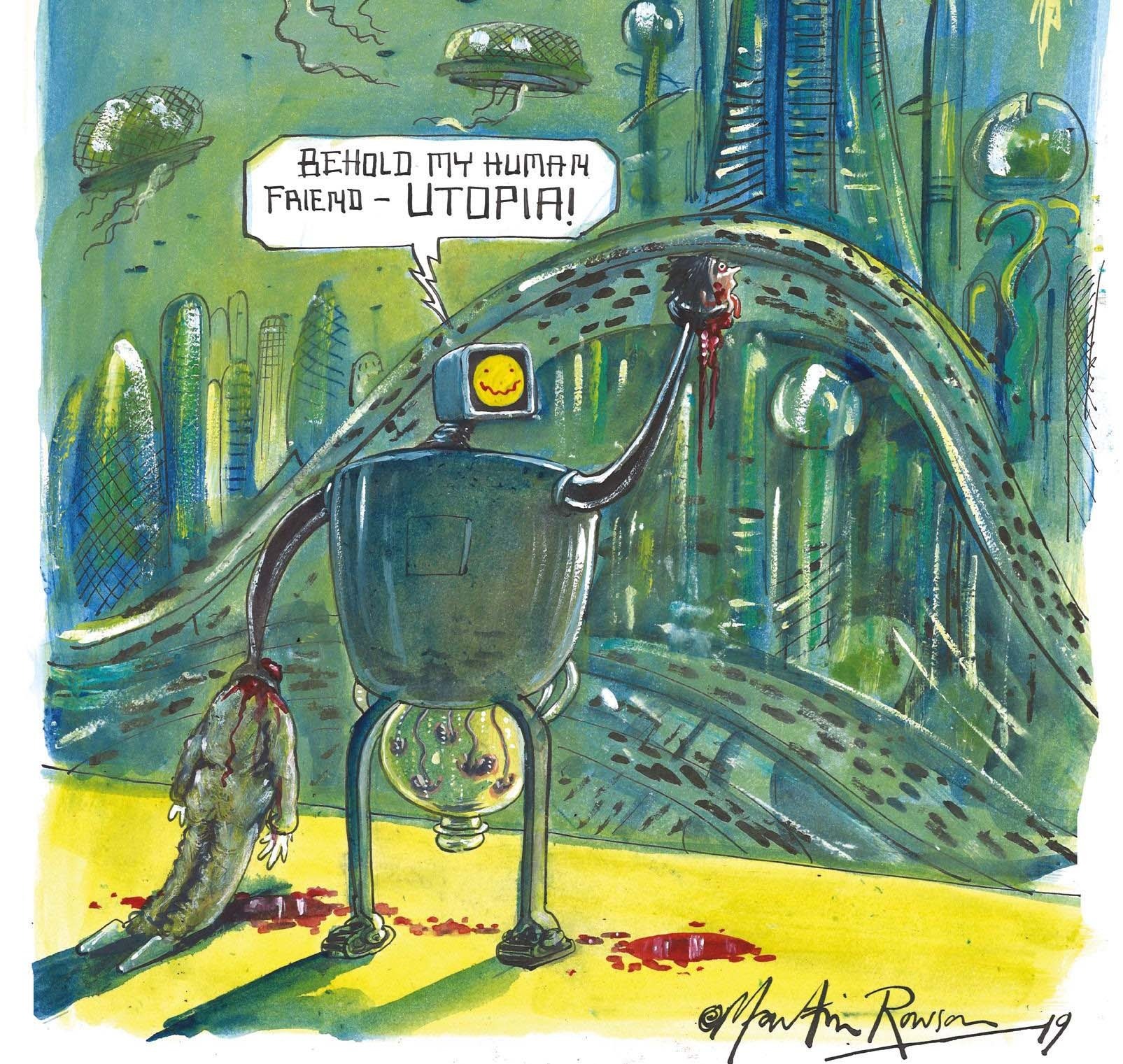

Traditionally, it is left-wing and radical anti-establishment thinkers who have taken it upon themselves to imagine new worlds and utopias in turbulent times. Yet the shelves look surprisingly bare when it comes to how we might harness our current advances in technology to pursue the betterment of all humankind. What optimism there is often seems to come from the top down – from the tech billionaires and internet giants.

Three books out this year buck the trend by proposing radically new approaches and ways of thinking in order to shape our future. Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism is perhaps the most straightforward of the set, loudly proclaiming the revolutionary potentials of technological advancements across the key industries – energy, agriculture, transport, health, retail and space. Bastani is the firebrand co-founder of Novara Media, a platform that has been loud in its support for Jeremy Corbyn and Labour’s grassroots movement Momentum. Fully Automated Luxury Communism, or FALC as it is cheekily known in left-wing meme culture, is an attempt to apply Marxist theory to our hyper-digital era. But Bastani doesn’t get too bogged down with the ins and outs of dialectical materialism. His aim is to show that it is at last technically possible to deliver a society of relative abundance for all. “Communism is being used here for the benefit of precision; the intention being to denote a society in which work is eliminated, scarcity is replaced by abundance and work and leisure blend into each other.”

Today, nearly 20 years after the music-sharing network Napster was shut down, most people understand that the cost of our digital products is kept artificially high. Bastani argues that the price mechanism is failing across various fields. It is not only information that wants to be free – it’s energy and labour, perhaps even food and minerals too. The book sets out to show how the plummeting cost of solar power, with global solar capacity doubling every two years, means that a future of clean, abundant energy is well within our grasp. A chapter on “Mining The Sky” argues that asteroids could provide humankind with mineral abundance beyond our comprehension. Another demonstrates how switching to synthetic meat could require 90 per cent less land and water than current meat production, limiting the need for global food distribution and rewilding vast swathes of the planet. Developments across the various fields all push in the direction of automation, decreasing the need for human labour and giving us the luxury of more free time.

* * *

As an attempt to outline humankind’s capabilities, were our skills and resources directed towards the public good, unhampered by the profit motive, it is a stimulating intervention. Yet it’s hard to see what elevates this book beyond an exercise in blue-sky thinking. Bastani is not a determinist. He freely admits that these new technologies are morally ambivalent and could go either way. “There is no necessary reason why they should liberate us, or maintain our planet’s eco-system, any more than they should lead to ever-widening inequality and widespread collapse.”

Yet little space is reserved for how we might avoid the latter and achieve the former. The call for a red and green populism looks a lot like Labour’s Green New Deal, including wide-scale public investment and the roll-out of renewable energy. You may agree or disagree with that policy agenda, but it’s a leap to assert that these changes will magically birth Communism 3.0. Late in the book, Bastani asserts that “FALC is not a manifesto for the starry-eyed poets”, pointing out that many of the technologies he’s writing about already exist in the here and now. This is disingenuous, as the point is how we choose to use them. For example, the world could go vegetarian today, without any reliance on synthetic meat production. As Bastani well knows, nothing short of a total revolution would be needed to bring about his vision. Fully Automated Luxury Communism is fascinating on the dazzling possibilities of the present, but hardly functions as a roadmap to the future.

At first glance, the broadcaster Paul Mason’s Clear Bright Future: A Radical Defence of the Human Being bears striking similarities to Bastani’s book. Both are self-proclaimed Marxists who draw heavily on the lesser-read early works, notably an unfinished and obscure text called The Fragment on Machines. In it, Marx seems to predict the advent of automation, showing how capital unintentionally reduces the need for human labour, creating the conditions for our emancipation from work. Like Bastani, Mason believes that this is within our grasp and that we should “aim straight for the goal of a classless, cooperative and fully automated society.” Sounds a lot like FALC to me.

Yet for Mason, it’s not enough to place new technologies in the right hands. We’re facing a far more existential threat – a dangerous and insidious ideology that Mason believes is rife within the political left just as much as the right. The book is a defence against what the author describes as the biggest attack on humanist values since their formulation. Anti-humanists, according to Mason, have lost their faith in our exceptional status as a species. The view that “we are just a collection of bones, brains and DNA” has become “very popular” in modern secular societies. The book presents this as an existential threat. “The idea that humanity is already over is deeply embedded in modern thought, from the alt-right to the academic left,” he writes. “The consensus is – from Silicon Valley to the HQ of the Chinese Communist Party – that human values have no foundation; that there is no such thing as human nature, no logical basis to privilege humans over machines, no rationale for universal human rights.”

The book is particularly concerned about the development of artificial intelligence. This is not a new line of critique. Jeanette Winterson’s recent novel Frankenssstein, reanimating the 19th-century Gothic classic to confront the challenges of today’s machine learning, reminds us of how old this fear really is. Where Mason departs from this is that for him, the danger doesn’t centre on robots aping humans. According to his thesis, it matters less whether Google’s Duplex assistant has or hasn’t passed the Turing Test. The problem is that we’ve already begun to see machines as potentially equal to ourselves. In fact, our 21st-century society has been primed to cede control, just as we allowed the financial markets to dominate our everyday lives while no longer serving our best interests.

* * *

In recent years, the debate on whether robots should have rights has begun to move in from the fringes. A Transhumanist Bill of Rights has already been drawn up by Zoltan Ivstan, a maverick writer and entrepreneur who ran for the US presidency in 2016. But can we extrapolate a general trend? Mason provides some interesting reflections. He cites the neuroscientific studies showing that we frequently act before our brain makes a conscious decision to do so, and the conclusion by some within the field that this challenges the existence of free will. Yet this is something of a niche field. Citing the popularity of Game of Thrones and other “fatalistic” narratives, as Mason does, seems to be reaching a little too far.

Then there is the issue of how we got here. Mason takes us on an intriguing journey touching on diverse figures from Oswald Spengler to Hannah Arendt, the billionaire tech investor Peter Thiel to the cyber-feminist Donna Haraway, with detours through the worldviews of Donald Trump and the Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Finally he seems to place much of the blame at the feet of the early post-modernist thinkers and the declaration by cultural theorist Michel Foucalt in 1966 “that man might be ‘erased’”. This is the familiar critique that cultural relativism has undercut the scientific method and advanced the dangerous idea we have adopted today that “nothing is true”. (Peter Salmon has discussed the nuances of this argument for New Humanist in several pieces, most recently in his essay on postmodernism and truth in our Spring 2018 edition.)

Instead, Clear Bright Future proposes Mason’s version of a humanism fit for the 21st century. This would place the values of knowledge and free inquiry alongside a belief in objective truth and the unique status of the human species. The book sets forward some interesting propositions, including creating “a comprehensive human-centric ethical system for AI” based on virtue ethics and regulated by law. This is a salutary aim, but a slippery task in practice, and Mason makes little engagement with the field of computational ethics as it stands.

Crucially, Mason proposes that his new brand of humanism would throw off the shackles of the past: “we are not defending something specifically ‘white’, male or even European.” Yet his critique of cultural relativism sits uneasily with this aim. His take on Donna Haraway and her 1984 Cyborg Manifesto is particularly telling, as he admonishes her anti-humanism in wishing to banish the dualisms of “mind versus body, nature versus machine, even man versus woman”. This anxiety towards dissolving binaries is in danger of putting him at odds with the very people he says he wishes to include in the humanist project: “the transgender activist in London, the female factory worker in Guangdong, the Kanak teenager fighting for independence on New Caledonia”.

* * *

It is precisely the capacity of technology to dissolve and reshape boundaries that feminist and queer thinkers have celebrated as liberating. The term “cyber-feminism” was coined in 1994 as a loose umbrella term encompassing anything from women working at the frontiers of tech to thinkers and activists approaching new and existing technologies as tools through which to free humankind from gender inequalities and constraints. Sophie Lewis’s Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family is a thrilling new intervention in the tradition, which is widely regarded as having reached its peak in the 1990s. Full Surrogacy Now imagines a world in which mothering is uncoupled from pregnancy and “baby-making can best be distributed and made to realise collective needs and desires”. Lewis draws on radical thinkers from second-wave feminism, notably Shulamith Firestone, whose controversial 1970 book The Dialectics of Sex advocated the elimination of the family unit, proposing instead that the roles of baby-making and child-rearing are shared across the community.

Lewis proposes surrogacy as a tool with which to dissolve the family. She points to speculative narratives we can draw on to inform this transition, such as Marge Piercy’s vision of ex-utero gestation and radically communal childcare in her 1976 sci-fi novel Woman on the Edge of Time, although she is also quick to say that we don’t have to wait for new technologies to be developed. “The aim is to use bourgeois reproduction today (stratified, commodified, cis-normative, neocolonial) to squint towards a horizon of gestational communism.”

Surrogacy is a growing global industry. In the UK, the number of parental orders made following a surrogacy birth has quadrupled since 2011. Full Surrogacy Now doesn’t shy away from these exploitative realities, including the lack of adequate medical care, the frequency of payment-related abuses and the crucial issue of consent. “From Bucharest to Bangalore,” Lewis writes, “most surrogates do not understand what surrogacy really entails.” However, the book argues that a ban would ultimately prove counterproductive, for many of the same reasons that banning sex work can be harmful, driving it underground and giving women less protection and choice.

We don’t need less surrogacy, Lewis suggests, but more. We’re not only invited to imagine a queer revolution in reproductive labour but also to look through Lewis’s eyes at a vision she already sees manifesting. “Everywhere about me, I can see beautiful militants hell-bent on regeneration, not self-replication.” Like Haraway and Sadie Plant, another key cyber-feminist thinker, Lewis’s prose is poetic and incendiary, shifting from the universal to the personal. Yet as with Fully Automated Luxury Communism there is a tension between a vision of the possible and the constraints of the probable. The difference is that Lewis acknowledges this, describing her vision as moving towards “a utopian horizon”.

* * *

July marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. We are yet to answer Gil Scott-Heron’s famous poem “Whitey on the Moon”, written to mark the 1969 landing. The poem, with its brutal first lines “A rat done bit my sister Nell / with Whitey on the moon”, is an indictment of “progress” in the context of stark inequalities of class, race and gender.

All three books, in their different ways, attempt to meet this challenge. Fully Automated Luxury Communism tackles it head on; by placing reproductive labour at the centre of her vision in Full Surrogacy Now, Lewis confronts a central issue that continues to be sidelined in the male-dominated field of futurism. By proposing a 21st-century humanism, Mason is defending our potential from perceived threats on both left and right.

But the Scott-Heron poem also asks us to look outside our front door before dazzling ourselves with heroic possibility. These books are a reminder of the heights we could be reaching. They have much less to say on how we might get there.

“Clear Bright Future” is published by Penguin

“Full Surrogacy Now” and “Fully Automated Luxury Communism” are published by Verso