This article is a preview from the Autumn 2019 edition of New Humanist

My older sister was explaining why her husband Arthur had refused to attend any more sessions of the local dementia group. “He seemed to enjoy it at first but then announced that he was not going again because there were always new people there.”

Now, although I sympathise with my sister’s predicament and hugely admire the manner in which she devotes so much her own life to caring for someone who is so evidently incapable of caring for himself, I can’t ever bring myself to tell her that there are some aspects of her spouse’s condition that I almost relish. For a start, he’s such a fine storyteller. Whenever our family gets together at a hotel for an awkward celebration of a birthday or a Christmas, I know that Arthur will cut through the usual chit-chat with a lengthy story from his Liverpool childhood.

He needs no prompter: “You know something, Laurence. In the old days I used to race cars in Bootle. We had a racetrack near the docks. A whole crowd of us. Mostly scrap cars. The rules allowed you to crash into each other. And, Laurence, I was a top driver. You should have seen us. Going hell for leather. Really big time drivers started there. Stirling Moss used to come some weekends.”

It doesn’t matter much to me that there were never thousands of people watching Arthur racing his scrap car or that Strling Moss never went near the Gladstone Dock. I know very well from my sister that whenever Arthur can’t remember, he simply confabulates. Makes things up. That may well be a symptom of dementia but it’s also the mark of any good storyteller, and a welcome antidote to the usual familial chat about the weather and the price of butter.

There’s another unexpected bonus. When I get home from these outings, I’m moved to examine how I cope with the oddities of my own memory. Why is it that I can remember holding hands with Jill Buxton in Sutton Park when I was six or seven years old – I can recall the blue skirt she was wearing and how she liked to make daisy chains – but have almost no distinct memories of the seven adult years I spent living with Louise? Freudian explanations hardly help. Although I can’t remember details of my life with Louise, I’m certain that it was never characterised by anything sufficiently disturbing to merit repression. But forgetting Louise, the sound of her voice or how we spent our evenings together is only one example of how my memory plays tricks.

Consider chronology. My memories no longer seem to have a beginning or an end. Instead, they arrive like clips from an otherwise forgotten film. I’m climbing a tree to find a kestrel’s nest. I’m stirring raspberry jam into a bowl of semolina. I’m running across a field to catch a train from Loughborough station. There’s no before or after to any of these scenes. They’re unprompted. Unbidden. Irrelevant.

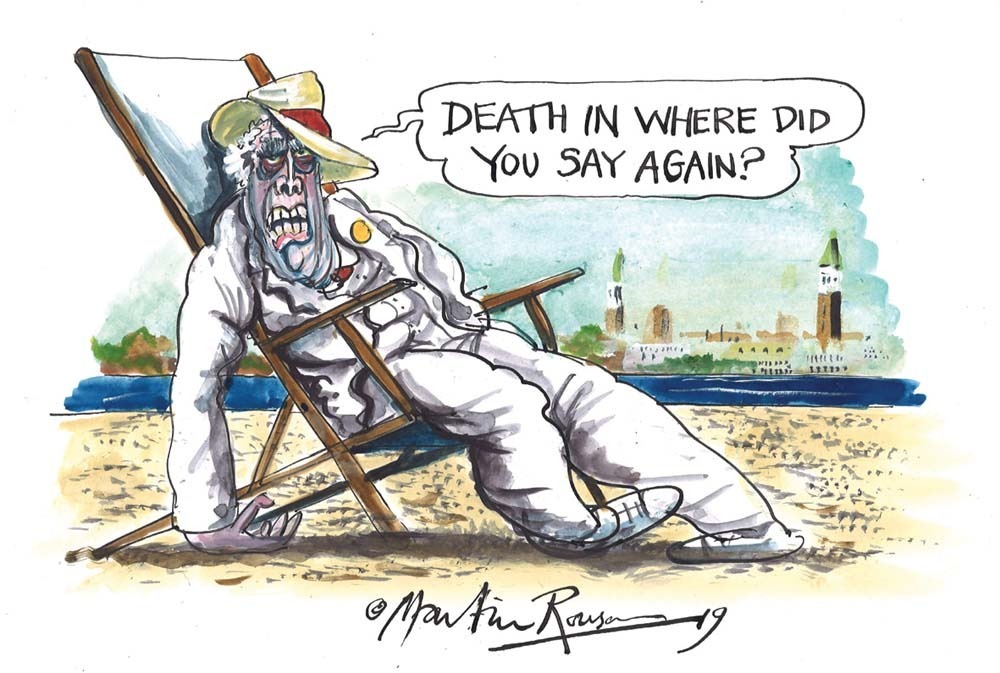

“Have you ever been to Venice?” asks my partner one evening as we’re watching Dirk Bogarde dying in his Lido deckchair. “Oh yes, I was there for a month. Reading Ruskin. Looking at the Tintorettos.”

So far, so good. I’m remembering. But then the crunch questions. “What was it like? Was it wonderful?” And that’s when memory acts up again. Scenes come to mind: the Rialto Bridge. Ruskin’s house. Coffee at Florian’s in St Mark’s Square. But they lack any emotional colouring. Was I blissfully happy when I gazed at the Carpaccios in the Accademia or plunged into Aschenbachian gloom by the sight of tour parties queuing to climb the Campanile?

There’s little everyday psychology to explain these oddities of memory. A good memory is prized. A poor memory is to be regretted, even taken as an ominous precursor of dementia. There are no prizes for forgetting.

But Arthur, magnificently, contradicts such a melancholy diagnosis. He is, and always has been, a Liverpool FC supporter. He watches their every match on television and exults in every victory. “We’re winning. We’re winning,” he shouts as the Reds score an opening goal. That’s not, however, the limit. When Liverpool score again, he’s quite forgotten their earlier goal and can greet the second with all the rapturous enthusiasm of the first. Perhaps it’s the occasional benefits of wholesale forgetting that give so many otherwise cruel dementia jokes a strangely triumphant tinge. Doctor: “I’ve got some bad news. You have cancer and you have Alzheimer’s.” Old man: “Well, at least I don’t have cancer.”