This article is a preview from the Spring 2020 edition of New Humanist

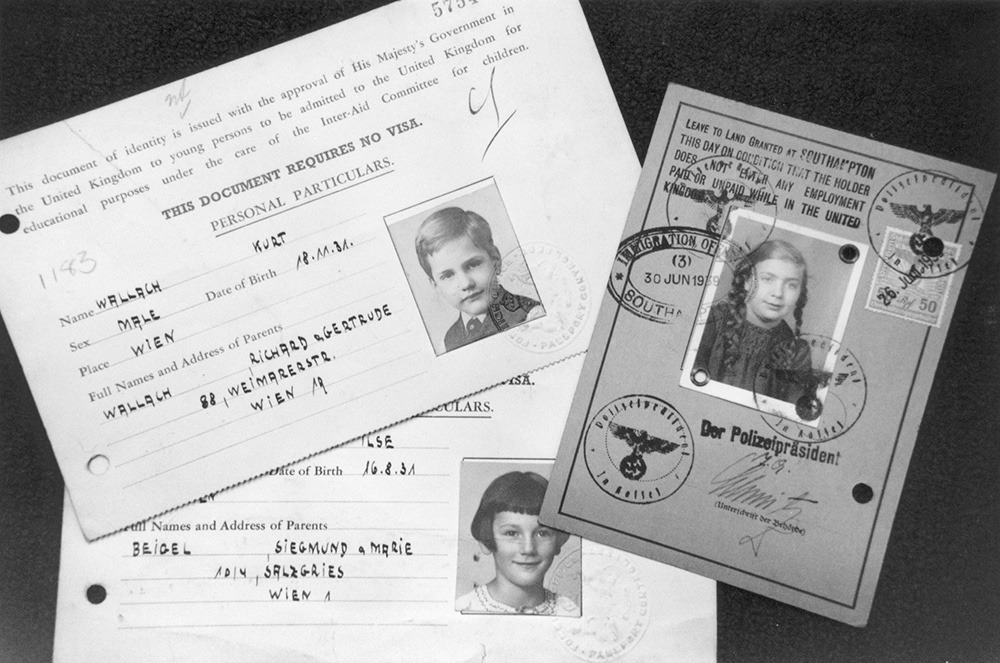

Two small public sculptures at Liverpool Street Station commemorate the Kindertransport, the exodus of 10,000 Jewish child refugees sent to London by their parents between December 1938 and September 1939, before war was declared and the exit barriers came down. “Für Das Kind” by Flor Kent and “The Arrival” by Frank Meisler portray children sitting on suitcases looking anxious and lost. Most never saw their parents again. The last-minute migration was later mythologised as a rare redemptive episode in a savage war which left tens of millions dead. Set against such numbers, the humanitarian gesture of sanctuary was welcome: but in the order of things it was a token gesture.

In The Kindertransport: Contesting Memory, historian Jennifer Craig-Morton unpicks the celebratory narrative that made so many politicians and the British population feel good about themselves. They had, one commentator wrote at the time, opened “up their homes and their hearts” to achieve “something worthy of the name of the British nation”. The story was framed as a modern fairy-tale, whereby the kindness of strangers led to lives lived happily ever after. Without questioning the good intentions behind the exercise, Craig-Morton suggests that for many children the resettlement proved traumatic, leaving lifelong scars and bitter regrets.

Why did this much-lauded episode in 20th-century refugee history prove to have so many troubling consequences? As Craig-Morton reveals, all of the organisations involved in the resettlement had a vested interest in telling a story of success, partly to cover up the fact that they were inexperienced in the basic elements of child protection and welfare. Siblings, including twins, were often separated on arrival and sent to different parts of the country, where some foster parents forbade contact with surviving family members. The motives of those offering to provide homes for the young refugees were mixed, ranging from the heartfelt and loving to the shockingly venal. Poor organisation coupled with a suggested obligation on relatives or co-religionists alone to provide new homes undermined the spirit of universal altruism that in other circumstances might have flourished more easily.

In rebalancing the story of the Kindertransport, some will argue that Craig-Morton has over-emphasised its negative aspects, and point to the success stories that emerged. The power of her account, nevertheless, resides in taking the children’s side – then, as now, often ignored. One of the young settlers later recalled: “I came at the age of three and a half. I still don’t know where I belong. I was brought up in the Midlands. I went to a Christian school. I was no longer considered German. I was not considered English. I certainly wasn’t Jewish – my Jewish background was not nurtured. I am neither German nor English. I am neither Christian nor Jew. I would like to know, what is my identity?” At the end of their lives, many were still asking the same question.

Similar mistakes were repeated shortly after, involving British children, albeit in less harrowing circumstances. Following the outbreak of war in September 1939, the government ordered a mass evacuation from vulnerable cities and seaports to the countryside. In total nearly 4 million people, mostly children – including many of the Kindertransport children again – were compulsorily evacuated, and their subsequent story shared many of the same ingredients, one of which was the re-framing of the fostering arrangements as yet another fairy-tale of unalloyed goodwill and selfless generosity.

No doubt many evacuees were treated with kindness and affection. In the 1970s I interviewed a number of former evacuees, and some were still in touch with their wartime foster parents 30 years later, recalling their wartime adventure “in the sticks” with gratitude. Others, though, remembered being taken advantage of: assembled in village halls as if “at an auction sale”, to be picked off by would-be carers, with the older boys billeted out to farmers who were keen for a new source of unpaid labour, and older girls taken in as unpaid domestic servants.

* * *

Craig-Morton finishes The Kindertransport by remarking that “Although it is an uncomfortable conclusion to reach, many carers were more self-serving than selfless, and the instances of truly warm and reciprocally fulfilling placements were much rarer than the mythologies about the Kindertransport have purported.” She suggests that relatives made the least suitable foster carers, volunteer hosts were slightly better, but those who took in Jewish children as part of the national compulsory evacuation scheme “often proved the most caring”. It seems that familial and voluntary schemes were invariably weighed down with ambiguous moral obligations, involving understandings and financial arrangements, to which the children themselves were not party. By contrast, the government’s evacuation scheme applied to everybody equally (including the Kindertransport refugees), and was legally enforced in the national interest, with transparent financial arrangements securing the children’s status as paying boarders. It was also better supervised than many voluntary schemes.

War is a political disaster, but natural disasters produce similar ethical and organisational dilemmas. On 31 January 1953, Britain experienced its worst flooding for centuries, resulting in the loss of more than 300 lives overnight in East Anglia, many of them children. Six years later, Essex historian and County Archivist Hilda Grieve published The Great Tide, a definitive account of the disaster, paying particular attention to the role which volunteers, voluntary organisations and government agencies played in evacuating and resettling thousands of victims rapidly and effectively. What Grieve began to understand was the degree to which the “spontaneous mobilisation” of help and relief she described – and admired so much – owed its effectiveness to organisational links and affiliations developed during the Second World War. Civil and coastal defence bodies, army reserves, unionised railway workers and seamen, the Women’s Voluntary Service, the Red Cross, St John’s Ambulance Brigade, boy scouts and girl guides, churches, parish guilds and social clubs had all been to an extent militarised during the war, and inducted, however briefly, into the mechanics of disaster relief.

* * *

As both the wartime evacuations and the 1953 flood response demonstrated, in addition to voluntary effort, effective civic organisation proved essential. The absolute failure of civic government was graphically demonstrated in 2005 in North America, when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. In her persuasive study of this and other disasters, A Paradise Built in Hell, writer Rebecca Solnit excoriates the public authorities for their dereliction of duty. “Thousands of people survived Hurricane Katrina,” she writes, “because grandsons or aunts or neighbours or complete strangers reached out to those in need all through the Gulf Coast and because an armada of boat owners went into New Orleans to pull stranded people to safety.” By contrast, “Hundreds of people died in the aftermath of Katrina because others, including police, vigilantes, high government officials, and the media, decided that the people of New Orleans were too dangerous to allow them to evacuate the septic, drowned city or to rescue them, even from hospitals.”

Solnit’s understanding of this and other “disaster communities”, where success or failure depended on public bodies harnessing the energy and altruism of community support and mutual aid, was confirmed by the recent Grenfell Tower disaster. Here the civic authorities failed to meet their responsibilities, compared with the tireless efforts of friends, family and neighbours to assist in every possible way.

* * *

How do people manage to build “a paradise in hell” in the face of such catastrophes, she asks, and what can we learn from these great waves of solidarity and support for the future? Worsening floods and forest fires across the world are producing new disaster communities almost every day. Solnit found one answer to this conundrum in the writings of the American philosopher William James in his 1906 lecture “The Moral Equivalent of War”. James suggested that war appears as a utopia for some by allowing people to attain a dignity in the service of the collective otherwise denied in normal life. He went on to consider other circumstances in which such social altruism might occur.

Six weeks after that lecture, an earthquake struck San Francisco, close to Stanford University where James taught. He quickly saw an opportunity to observe how people coped in the immediate aftermath, and in an essay written shortly after, “On Some Mental Effects of the Earthquake”, wrote: “Two things in retrospect strike me especially . . . both are reassuring as to human nature. The first was the rapidity of the improvisation of order out of chaos.” The second was “the universal equanimity” found amongst those most affected. Both seemed then, and still do today, counter-intuitive.

James had only four years left to live, and spent much of that time reflecting on how society could build upon the “slumbering energies” released by war and its moral equivalents, but most particularly natural disasters. Today worsening environmental conditions, war and terrorism are forcing millions of people around the world to flee their homes in search of safety. Sauve qui peut, the French saying goes: save yourself. But what if somebody else has stolen or sold the lifeboats?

“History is a bath of blood,” James wrote in that first essay, arguing that throughout history, war has been celebrated as the apex of human capacities and virtues, embodying strength, courage, collective sacrifice and honour. As a pacifist he asked how these qualities could be marshalled to achieve other ends. One answer was the conscription of young people working for the collective good. The American Peace Corps was later established as a direct consequence, though the same lessons were learned by the powerful civil rights and community organising movements of the 1960s. In a volatile and uncertain future, it is best to prepare for the worst even while we hope for the best.

“The Kindertransport: Contesting Memory” is published by Indiana University Press