This article is a preview from the Summer 2020 edition of New Humanist

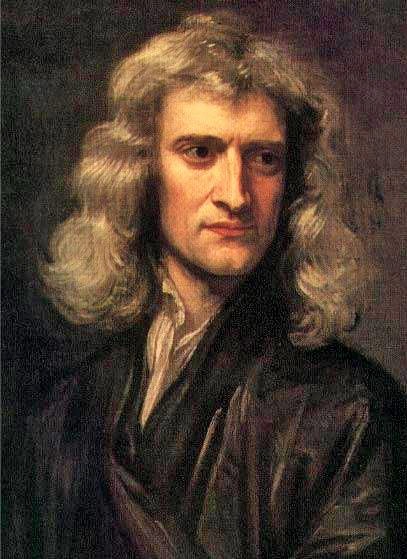

It is August 1665. Bubonic plague is raging in London. So great is the dread of contamination that in Cambridge, 55 miles to the north-east, the university is closed. A 22-year-old man, unknown, unremarkable, makes the trek by foot, by horse-drawn cart, back to his family farm in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire. There he will remain in self-isolation for 18 months, during which time he will not only discover the universal law of gravity but change the face of science.

Isaac Newton will not tell a soul about his law of gravity for 18 years. “To know something that no one else in the world knew or understood – that was a most exhilarating experience of power,” speculates the novelist and historian Peter Ackroyd. “Perhaps he wished to prolong it for as long as possible.” Only in August 1684, when his friend Edmond Halley visits him in Cambridge to ask a question about the paths of the planets, does Newton finally reveal his secret.

When Newton settles into life at Woolsthorpe, it is still summer and the air is alive with birdsong. It is hard to believe that, 100 miles away in London, people are stumbling and dropping in the streets. They are suffering fever, chills, muscle cramps and aching limbs. They are gasping for breath and sometimes coughing up blood. Their armpits and groins are swollen with black buboes as the plague bacterium multiplies in their lymph glands.

Woolsthorpe Manor is a slightly dilapidated two-storey dwelling with grey limestone walls, nestling amid apple trees and grazing sheep on the side of the valley of the River Witham. Newton, at his desk, shuts the horrors from his mind. He is a pragmatist. And a pragmatist might use a time of terror as an interlude, as a God-given opportunity to penetrate the mind of the Creator. In his “miraculous year”, Newton will discover the laws of optics and colours, the mathematics of “calculus” and the “binomial theorem”. But, most significantly of all, he will find the universal law of gravitation.

Newton asks himself a question even children ask: why does the Moon not fall down? And at Woolsthorpe, he finds an answer. He imagines a cannon that fires a cannonball horizontally. After only a short distance, it falls to the Earth. He pictures a bigger cannon that shoots a cannonball faster. The ball travels further before hitting the ground. He then imagines a truly enormous cannon that fires a cannonball at 28,080 kilometres an hour. For this cannonball, the curvature of the Earth is critical – as fast as the cannonball falls towards the ground, the ground curves away from it. Though perpetually descending towards the ground, the ball never gets any closer. Instead, it orbits round the Earth, falling in a circle.

In a searing flash of clarity, Newton understands that it is possible to fall and just keep on falling. Not just for a moment but for ever. That the Moon, though all appearance would refute it, is doing just that. And, in that understanding, he sees what has until this moment eluded him: the way to bring Heaven down to Earth, to unite the two realms in one beautiful, seamless, over-arching system.

If the Moon is falling, then it is doing what an apple plummeting from a tree is doing. Both are falling towards the centre of the Earth under gravity. Newton compares the rate of fall of the Moon and an apple, and, knowing the distance to the Moon, deduces how the pull of gravity changes with distance. If the separation between two masses is doubled, the gravitational attraction between them becomes four times weaker; if the distance is trebled, nine times weaker, and so on. It is this “inverse-square law” of force that Newton discovers in the spring of 1666.

It is an extraordinary leap of the imagination to recognise that the Moon is falling because of the same force that causes an apple to fall from a tree. At the time, the Heavens were believed to be the domain of angels and of God himself. The Greeks even imagined them made of an ethereal fifth essence, distinct from the everyday “elements” of earth, fire, air and water.

But Newton sees no distinction between up there and down here. In a world dominated by religious dogma, he has the courage to bring the Heavens down to Earth. The same laws that govern bodies on Earth govern bodies in the Universe. There exist universal laws – ones that apply in all places and at all times.

In London, a quarter of the city’s population – more than 100,000 – will be dumped in plague pits. But the miracle of the plague year is that in sleepy, rural Lincolnshire, Newton changes the world.