In the mid-seventeenth-century drawing pictured above, by the French painter Claude Lorrain, a shepherd reclines on a rock, lost in a dream or enchanted by the pipe player seated at the drawing’s left edge. In the foreground, a horned cow also listens, rapt. The shepherd with the crook against his knee; the musician with his flute; the grazing flock: it is a familiar bucolic scene from an era fascinated by the romantic promise of the pastoral. But these ideals are misplaced here. Adapted from ancient myth, the scene is one of imprisonment. The cow was once a woman, the priestess Io, metamorphosed by Juno in punishment for a crime she didn’t commit. To foil her husband’s violent interest in one of her priestesses, the goddess Juno demands that her sentinel watch over Io. This is the guarding shepherd in Lorrain’s scene, Argus Panoptes, ‘all-seeing’ Argus, not a shepherd at all but a multi-eyed Titan.

Bentham’s panopticon, which gives a centrally placed guard the power to see all members of an institution at any moment, is a more popular analogy for representing modern surveillance, but the watchful Argus might be a better symbol for today’s digital modes of scrutiny, especially AI systems that monitor work processes.

The Covid-19 pandemic has considerably, perhaps even inoperably, changed how we work. With an increasing number of employees working from home, companies have been forced to consider how to run their business digitally. Enter worker surveillance: Employees install the software to their computer, and the AI observes their every online interaction, from emails to internet surfing. These programs are, however, more than intelligent clocking-in systems. Claiming to improve work processes, surveillance software gives workers a ‘score’, a cumulated survey of productivity.

Why is this problematic? Management has often courted scientifically dubious practices. Some businesses use psychometric tests, or graphology to analyse employee handwriting, contending that such testing can improve the hiring process (claims that are not backed up by science). But while AI surveillance might belong to the same bargain bin of pseudo-scientific methodologies, this new tech-kid-on-the-block is more sinister, precisely because the AI continuously ‘tests’ its subjects by surveilling them, sliding the scale of their productivity up or down depending on their work output.

Consider the tale behind Lorrain’s pastoral landscape: The metamorphosed Io was once Juno’s priestess. Io served the goddess; she worked for her. And yet, through no fault of Io’s, Juno deemed her transgressive and transformed her into a cow. Through this metamorphosis, Io lost the ability to speak. Juno installed Argus (in our case: the artificial intelligence) to watch over her. It is a neat parallel: AI surveillance companies also project tranquil work scenes, where a company’s employees are not being punished but instead sit in harmony while a monitoring system guards them. But this is, as in Lorrain, an illusion: Behind the peaceful scene, something insidious is at play. The cow is not free at all—bound both by her inability to speak and by Argus. The shepherd may look as though asleep, yet he is always watching his charge.

When AI monitoring systems claim to use employee data to generate ‘productivity scores’, only a little scratching reveals the promise to ‘optimise’ employees as in effect aggregating the time they spent writing emails and surfing so-called ‘unproductive’ websites. There is no explicit advice as to what companies should ultimately do with the scores AI generates. But such surveillance strips workers of a voice in their own destiny: systems that measure productivity by quantifiable data make a case for leaning on the numbers. Trends, to trial some corporate euphemism, encourage companies to prune the bottom outliers.

Say such a system were to be in place at your office. The AI would measure your connections, the time you took to respond to emails, how quickly you completed a piece of work—all gauged against your coworkers’ response rates. But on which of your colleagues will these ideal scales be based? What would the repercussions be, if you were to (literally) fall out of line, and how much say would you have in the implementation of these measures in the first place?

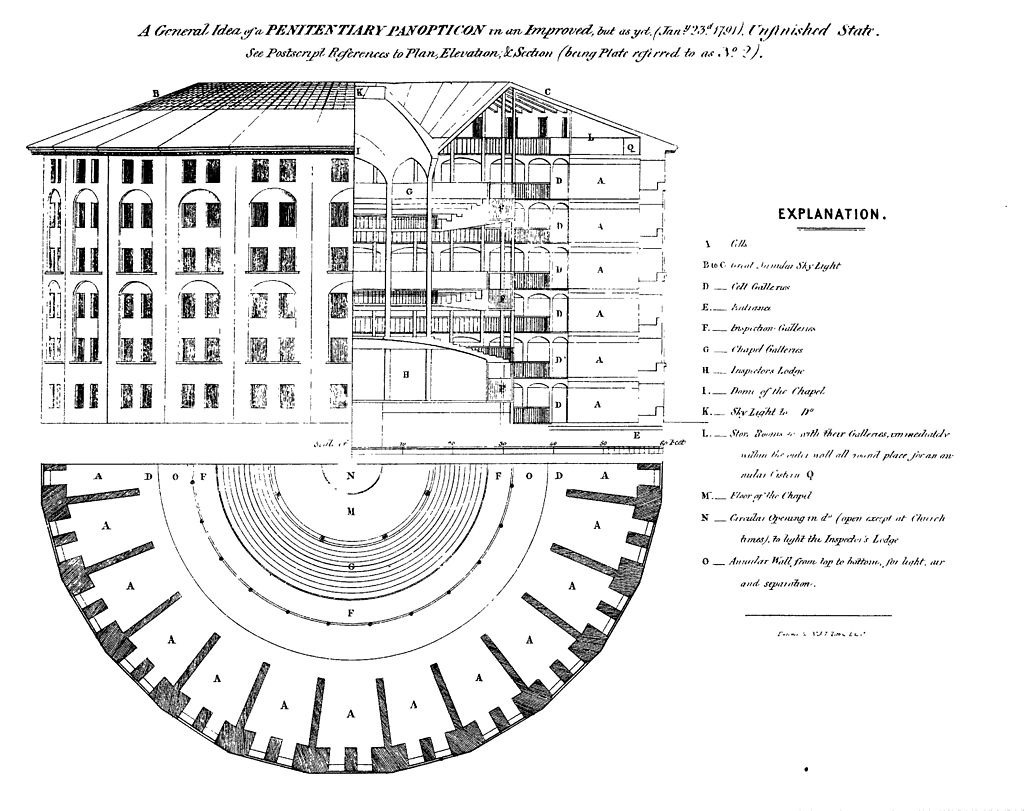

Bentham’s solution to improving institutions such as prisons that required surveillance was a structure where all ‘convicts’ could be watched at all times. His panopticon is a prison built in the round, with an inspector’s lodge at the center, from where a single guard could oversee everyone, crucially without being seen himself. Bentham’s promise was that this panopticon would reduce costs: If all prisoners knew that there was a possibility they were being watched, then they would be on their best behavior. And because none would know whether or not they were actually being watched at any given time, the guard could be relieved of permanent duty. Bentham’s vision was not for an era where twenty-four-hour surveillance was possible. His model, dependent on human alertness, cannot compete with something that is always capable of surveillance.

In Foucauldian theory, such measures to observe fall under the domain of punishment rather than encouragement. Unless we are onstage, no one actually likes to feel watched, even at work. Foucault’s concerns, which center on the status of the observed individual – ‘He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication’ – become a benefit for AI developers, where turning workers into objects of information is the unashamed point.

Stripping workers of their voice

We would expect two models of the same machine to look and function in a similar way, but people do not work exactly like each other. Monitoring systems cannot account for this individuality. They homogenise and relegate us to data points. Are workers to base their value on time rather than commitment and skill? Citizen scoring systems are rightfully decried. Corporate productivity scores should thus not be acceptable measures of a person either. At best, they are reductive. At worst, they are dangerous. What of ageing? Diversity? Humility? Empathy? What of distress, sorrow and finding ways out of them through work? Are such needs now mere luxury in a place where we spend most of our waking lives, virtually or not? Distilling our emotions, thoughts and skill into quantifiable data leaves out too much of the story.

Multiple studies show that people tend to work more productively anyway while at home than in the office, so, why the perceived panic in surveilling and scoring employees? By installing such systems, managers can avoid hearing their workers. AI monitoring companies claim to aid communication between managers and their employees. But while they may have revealed a critical issue – talking to each other – the way to improve communication is to learn to communicate. Monitoring will not do this; AI scoring takes away the worker’s opinion and installs instead a voice box powered by a computer. Surveilled employees, just like Victorian children, will be seen but not heard. If hard data tells you that something isn’t working, then it is the fault of its producer, in other words, the worker. The worker has no say in the use and abuse of their data, just as Io, turned into a cow, becomes literally voiceless.

So, who is the guard?

The Roman poet Juvenal’s satirical poetry lampooned his contemporaries. His question – ‘Sed quis custodiet ipsos Custodes?’ ‘But who will guard the guards?’ – frequently appears alongside Bentham’s panopticon and was originally postulated in mocking concern for marital infidelity. But the question has long been used to reveal structures of tyranny, ones perhaps no less apparent in today’s political climate.

We can also apply Juvenal’s question to monitoring systems. This forces us to first define the parameters. Who, after all, is the guard? With regard to software, roles of responsibility (of the programmer, of the owner, of the user) are not clear-cut. Is the manager the guard because they have jurisdiction over their workers’ data? Or does this role belong to the original programmer who designed the software’s architecture and therefore the principles of punishment?

In the instance of employee monitoring, both manager and programmer are the guards. The programmer is inevitable: All technologies have programmers behind them, and they are the people who define the parameters of the scoring system. The manager’s role as guard is less concrete. We should expect that, before using such software, those responsible in the company should understand the framework in which workers are being monitored, how those data are gathered and, most crucially of all, how results should be interpreted. This is a tough ask for a group of which 76% don’t consider themselves data literate. The manager-as-guard, then, is an incompetent and ineffective overseer, taking their cues from the biggest or lowest number, with little understanding of the process.

And so, to follow through on the Juvenalian question, who guards programmers and managers? Bentham’s response was to give responsibility to the general public and public administrators, but no private company will hand over their data to external ‘guards’. Here lies a double problem: 1) Who will judge the fairness of the processes by which workers are scrutinized? and 2) Which of the guards (programmer or manager) should be observed?

In the eighteenth-century, Jeremy Bentham created his own all-seeing monster. But Bentham’s panopticon (see the plan above) only literalised the first half of the ancient tale of Argus. In Ovid’s mock-epic Metamorphoses, which stitches together legends from Greece and Rome, Jove closes the Argus story. He instructs Mercury (the charming flautist in Lorrain) to put to sleep and kill Argus before setting the unfortunate Io free – or as free as she can be – for Juno sends down a gadfly to chase her (such are the inequitable trials of life). Left with the disembodied head of her guard, Juno then merely ‘repurposes’ Argus by placing his eyes into peacock feathers. Her sentinel may have been destroyed, but Juno has learned nothing from the process.

Companies should be working to find solutions that truly support their workers, rather than punishing individuals because of grades that have been artificially constructed by third parties. Will support really go to those designated as anomalies and outliers, or will they get siphoned off at the end of the year? At UCL, the project PanoptiCam installed a camera above Bentham’s displayed corpse as a means to open communication about surveillance. In considering the ethical implications of surveillance, the multidisciplinary UCL team concluded the project with the following statement: ‘We believe the observation of behaviour in public spaces is acceptable provided we do not identify individuals, but also that by filming them and their responses we don’t reasonably place the participants at greater at [sic] risk of criminal or civil liability, or cause damage to the participants’ financial standing, employability, or reputation.’ Who is listening to this warning, and on how many of these items does productivity scoring impinge?

The first step is to hold AI companies responsible for the psychological, social and economic effects their products have. Claims that their software improve work conditions must be backed up with concrete evidence. Promises that their service will improve communication in the company must be supported by proof. The second step is to ensure that the people using the software: are data literate and – most importantly of all – value what their employees say. This is not a question of whether or not companies have a right to monitor their employees. The question is how external companies gather data and expect managers to use such information.

The thrust of AI companies’ arguments for productivity in the workplace is that hard data cannot lie. But reliance on such information – without managers understanding how to interpret employee ‘scores’ – is a dangerous, paradoxically blinkered way to do business. Our (working) lives deserve to be measured in more than quantitative ways. Technology is touted as the great enabler of communication, and yet the sad reality is that many of us still do not really listen.