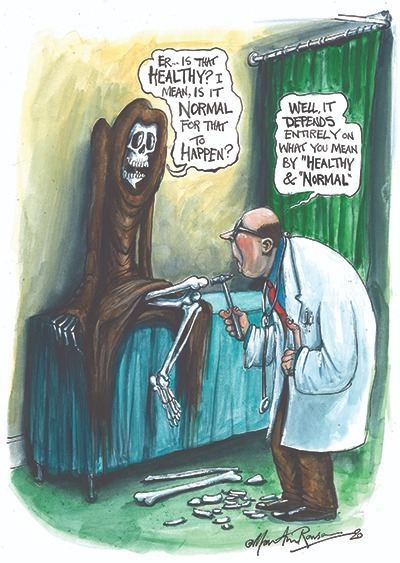

What does it mean to be healthy? What does it mean to be normal? Are they the same thing? And, conversely, what is it to be unhealthy? Is it a fact about being, and thus possible to adduce objectively, or is it a value which depends on the subjective interpretation of the patient or doctor? Or is it the set of medical, cultural or political norms of a given society?

The current health crisis has brought a new urgency to these questions, both at the level of medical science and in the social and personal sphere. In the internet era, it can seem as though every individual has become their own physician. We can access a vast amount of medical theory and anecdote which makes it possible to find fatalities for almost any disease and a disease for any symptom. Self-diagnoses have become quotidian. And in our present moment, amidst the chaos of the coronavirus pandemic, we are consumed by endless flows of information about possible causes, possible cures, morbidity rates and behavioural advice (all of which change continuously). As both personal and public duty, the conversation we have with our own bodies has become louder and more urgent.

The history of medicine is one of changes to the definitions of normal and healthy, sick and diseased. For a long swathe of human history, for example, homosexuality was defined as abnormal. It was only removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973, and remains pathologised in many cultures. Sickle cell anaemia is predominantly found in African and Caribbean populations, where it has a high morbidity rate. However, the cells which cause it also appear to have antimalarial properties, making them a biological advantage in places where malaria is endemic.

Furthermore, many carriers of different diseases are asymptomatic. One can live with HIV without getting AIDS, and one can have latent tuberculosis without being aware of it. No one in apparently “perfect health” is in perfect health.

Given these inconsistencies, how can we really define disease? Is it an entity which in some sense exists independently of the human that “has” it (as when “Susan has a cold”), or is it a process which can only be identified in its dynamic interaction with its host, such as the growth of cancer cells? Or is it simply a set of conventions? Classifications change over time – “fever” was once thought of as a disease and is now a symptom, and epilepsy was once considered a divine state, but is now a disease.

* * *

It is this question of health and illness which the notable French philosopher Georges Canguilhem explores in his radical intervention into medical philosophy, The Normal and the Pathological. First published in 1943, the book investigates the two concepts of the title across medical history and in their contemporary definitions.

Trained in medicine – as unusual then as it is now for a philosopher – Canguilhem is, within France, regarded as one of the foremost philosophers of the 20th century, not only for his own work, but for his influence on his students, who included Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Pierre Bourdieu and in particular Michel Foucault, who was to expand on Canguilhem’s fundamental insights in his explorations of the archaeology of knowledge.

His influence was not simply academic. As a professor at the Sorbonne and as inspector general and then president of the Jury d’Agrégation in philosophy (the national educational accreditation board), his role was to evaluate the early work of these formidable thinkers, and he was not one to suffer fools or academic sloppiness. Derrida was told that he needed to prove that he was a serious thinker before staking a claim to iconoclasm (advice that he just about managed to follow), while Althusser was to write that Canguilhem was “one of our old masters, a fierce man, angry, shy and violent, who convinced himself, after years of mistrust, that we really loved him”.

The Normal and the Pathological opens up the field of science and history, framing science as encultured and non-neutral. Canguilhem takes as his starting point the rapid developments in medical biology in the 19th century, in particular the emergent disciplines of physiology – the study of the body as a system and its normal functioning – and pathology, the study of its illnesses. Generally held to be inaugurated by William Harvey’s 1628 discovery of the circulation of the blood, the field of physiology had increasingly come to treat the human as a kind of machine, the organs of which worked in harmony with each other.

Advances which consolidated this view of the human body included three strands: cell theory, which broke the organs down into smaller units and, as Canguilhem notes, has a visual analogy with the cells of a beehive, thus suggesting industry; germ theory, which included the discovery of bacteria and then viruses, which conformed to the model of objects from outside which enter into the object of the body; and immunology, in which the army of the body fights the army of the disease.

In the emergent field of physiology, the body was thought to seek homeostasis – a steady state in terms of such things as temperature, heartbeat, blood pressure and so forth. In each of these metrics, there is an ideal that

possibly applies to all humans but certainly to any given individual. A pathology, then, is something which interrupts this normal functioning, a spanner in the works. For 19th century western physiologists, whose models and analogies continue to inform how we view disease, the difference between the normal and the pathological is quantitative. There is normotension, where an individual’s blood pressure is within the homeostatic range, but there is also hypertension, when it is above, and this is pathological.

These conditions presuppose that the normal state can be defined in an objective way as a fact about humans. However, as we have noted, normality can be site-specific (as in the case of sickle cell disease) or time-specific. For example, not being able to talk is normal for a three-month-old baby, but not for an adult. Physiological averages can vary wildly across societies and within individuals.

* * *

What is described as normal, therefore, in the sense of numerical pervasiveness or statistical averageness, needs to be distinguished from the normative, with which it is often conflated, if not confused. The normative is “evaluative”: it is an imposed criterion for judging whether something is desirable or good. In medicine, that which is considered normal (a fact) is often normative (a value). The longstanding definition of homosexuality as an abnormality is a good example of this.

Thus for Canguilhem, “the normal man is not a mean correlative to a social concept, it is not a judgment of reality but rather a judgment of value.” There are no value-free assessments of normality or disease – excess and deficiency exist, he writes, “in relation to a scale deemed valid and suitable”. For instance, for “a disability like astigmatism or myopia, one would be normal in an agricultural or a pastoral society but abnormal for sailing or flying.”

In this way, Canguilhem challenges declarative statements in medical science and their designation as “existents” which can be defined and kept separate from each other. For Canguilhem, these norms are theoretical abstractions – a mathematisation of individual experience. A medical average is not necessarily the ideal for a particular person. He quotes the example of the physiologist “who took urine from the urinal at the train station through which passed people of all nations, and believed he could thus produce the analysis of average European urine”.

This is not to argue that averages and other such abstractions cannot be useful, only that they can in fact become harmful if they are taken to actually represent disease and the experience of disease itself. To be sick is to live another life. “The living creature,” Canguilhem writes, “does not live among laws but among creatures and events which vary these laws.” Or more colourfully, “What the fox eats is the hen’s egg, and not the chemistry of albuminoids or the laws of embryology.”

Life as an object of science cannot capture life as it is lived, and it is in illness that we live the most intimate and mysterious of scientific puzzles. As Canguilhem puts it, the concept of the norm “is an original concept which, in physiology more than elsewhere, cannot be reduced to an objective concept determinable by scientific methods. Strictly speaking then, there is no biological science of the normal. There is a science of biological situations and conditions called normal. That science is physiology.”

Normalcy, then, for Canguilhem, is “not static or peaceful, but a dynamic and polemical concept”. Because it is individually specific, it is a concept best generated by the patient. A person is healthy “insofar as they are normative relative to the fluctuations of their environment” – insofar, we might say, that they can achieve their functional aspirations, be they practical, emotional or other. That being the case:

The borderline between the normal and the pathological is imprecise for several individuals considered simultaneously but it is perfectly precise for one and the same individual considered successively.

We are, he notes, “sick in relation not only to others but also to ourselves”.

Medical science is, Canguilhem argues, a domain of knowledge and, like all domains of knowledge, it is not purely objective – economic, cultural and technological imperatives are always already present in its creation. Foucault is known for extending this insight into other fields, in particular the realm of mental illness and sexuality, concentrating on the way that signifiers such as “sane” or “mad” are the result of relationships of power. Most directly, his 1963 text The Birth of the Clinic examines the way the medical gaze reorganised medical knowledge in the late 18th century to separate the person and the patient, the person and the disease. “In order to know the truth of the pathological fact,” writes Foucault, “the doctor must abstract the patient ... paradoxically in relation to that which he is suffering from, the patient is only an external fact.”

The dominant positivist account of scientific progress in medicine (as in other disciplines) argues that knowledge is steadily accumulated, eventually leading to absolute understanding. Canguilhem contends that this is doubly false. First, it takes the idea of progress and the process of naming as neutral. Second, it portrays scientific progress as a movement from ignorance to absolute knowledge. As Canguilhem points out, the scientific truth of today (or any day) is always merely an “episode” in truth, which meets no absolute criterion, but is instead manufactured by any number of factors. “The germ theory of contagious disease,” he writes, “has certainly owed much of its success to the fact that it embodies an ontological representation of sickness. After all, a germ can be seen. . . To see an entity is already to foresee an action.”

* * *

Medical knowledge works, therefore, by a chain of analogies. Further, like all sciences, medical science works by inductive logic: a theory cannot be proved, only proved wrong. If the sun rises every day, I can argue that there is a strong likelihood it will rise tomorrow. If it doesn’t, my theory was wrong and no number of sunrises can prove it right. Gravity cannot be “proved” – rather, as a model it displays greater predictive power (up to and including all situations) in dealing with a greater number of physical events (up to and including all of them) than any other theory.

In addition, of all the sciences, medical science remains the most complicated, both in terms of diagnoses and prognosis, and in terms of effectiveness of intervention. In their 2011 paper “Uncertainty in Clinical Medicine”, Benjamin Djulbegovic, Iztok Hozo and Sander Greenland wrote: “It occurs at the intersection of science and the humanities, situated at the crossroads of basic natural sciences (i.e. biology, chemistry, physics) and technological applications (relying on the application of numerous diagnostic and therapeutic devices to diagnose or treat a particular disorder). It occurs in a specific economic or social setting (each with its own resources, social policies and cultural values).”

Moreover, “It essentially involves a human encounter, typically between a physician and a patient.” Unlike the raw material of, say, an experiment in physics, a medical experiment – which is what every doctor–patient encounter remains – does not take as its subject an inert material which yields predictable results. Nor is the practitioner – the physician – able to extract themselves from the experiment, as is the aim of scientific best practice in other fields.

Neither the patient nor the physician needs to act in bad faith to exacerbate this complication. The physician-patient encounter is not not only a case of making predictions; it is, at least initially, making predictions from indirect evidence. It is the patient who decides they are unwell, and it is initially through verbal communication that the symptoms are presented. These initial descriptions cannot help but be partial and subjective – the severity, persistence and location of a stomach ache, which may or may not be related to another symptom, is not, in any understandable sense, fully communicable. In Canguilhem’s words:

It is impossible for the physician, starting from the accounts of sick individuals, to understand the experience lived by the sick individual, for what the sick express in ordinary concepts is not directly their experience but their interpretation of an experience for which they have been deprived of adequate concepts.

For a physician, it is difficult to maintain the abstractions of diseases-as-classified when talking to actual patients whose symptoms, and presentation of symptoms, cannot, by definition, map directly onto those diseases. The accuracy of any prediction about outcomes does not necessarily correlate to the severity of the disease or the accuracy of the diagnosis. Recent studies show that prognoses of the outcomes of cancer treatment hover around the 30 per cent accuracy mark.

The messiness of the diagnostic encounter is not, of course, fatal to medical science – its successes are tremendous at the level of history and society, and often at the level of the individual. And yet the discourse around medicine, particularly during the coronavirus crisis, has fastened to a large degree on the mathematical modes of medical science, from statistics around death to the positivist notion of a logical progression towards a vaccine. Newspaper reports about scientists supposedly “proving” the efficacy (or inefficacy) of a particular medical or pharmaceutical technique have come thick and fast. Even those who regard medicine as malign, such as anti-vaxxers, frame their arguments in the jargon of science.

Public health, whether done badly or well, has its own set of competing imperatives, over and above the individual encounter between doctor and patient. It incorporates epidemiology, statistics and biology, but also economics, architecture and civic planning. It is a political discourse which, as we have seen, must play to particular constituents, ideally balancing this with an obligation to truth telling insofar as such a thing is possible. As Foucault argued, “The first task of the doctor is political: the struggle against disease must begin with a war against bad government.” It is another front of the battle against disease: a public front.

* * *

And yet, for those who are ill, for those who are fighting their own private battle with their inability to function as they wish, the public version of their illness is no more or less true than the abstract version. It is yet another competing narrative into which their body has been inserted. They are expected to put up a fight, as though immunity were an army of which they are the general, able to muster and direct their forces by the strength of their moral goodness. Disease, Canguilhem writes, is envisioned as “a polemical situation: either a battle between the organism and a foreign substance, or an internal struggle between opposing forces”.

This is a model, dominant in much medical discourse including the current crisis, that privileges disease as a problem for which there is an absolute and knowable solution, as though “disease tokens [could be] separated from the body and displayed on their own”. In this model, the messiness of medical diagnosis is effaced – all symptoms point to a disease, all diseases point to a resolution (good or bad), and a failure of identification is a failure of understanding, rather than a signifier of the complexity of the issues.

As Canguilhem writes, “The living being, having been led, in his humanity, to give himself methods and a need to determine scientifically what is real, necessarily sees the ambition to determine what is real extend to life itself. Life becomes – in fact, it has become so historically, not having always been so – an object of science.”

For all those self-diagnosing, this creates its own anxieties. At once distanced from our body as it becomes an object of study, and brought into intimate contact with the idea that it might get sick and die, taking us with it, we stand at the point between. As Canguilhem’s near-contemporary Gabriel Marcel put it, life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived. In Canguilhem’s words, “We maintain that the life of the living being, were it that of an amoeba, recognises the categories of health and disease only on the level of experience, which is primarily a test in the affective sense of the word, and not on the level of science. Science explains experience but it does not, for all that, annul it.”

From the autumn 2020 edition of New Humanist.