The political landscape in Britain is becoming more toxic by the day. Or so it can seem, with ordinary people increasingly identifying themselves by their tribes – left/right, Labour/Tory, Leave/Remain – while these very labels are often used as slurs by the other side. Divisive politicians and angry commentators pander to our biases, creating a culture of contempt, through what social scientist Arthur Brooks has called the “Outrage Industrial Complex”.

But is this antagonism equally fierce on either side? Evidence is emerging of an intriguing asymmetry between how the left and right view each other on an interpersonal level, with the left apparently proving most hostile. Last year, a YouGov survey found that 34 per cent of Labour supporters would be upset if their child married a Conservative, whereas only 13 per cent of Conservatives would be upset with a Labour in-law.

Furthermore, a Hostility Barometer survey conducted by LSE found that 68 per cent of Labour voters felt disgust towards Conservative voters, while 48 per cent of Conservatives felt the same way about Labour voters. A quarter of Labour voters said they wouldn’t invite a Conservative voter for dinner, compared to 16 per cent of Conservatives.

What’s driving the asymmetry in those numbers? Is this an empathy blind spot, or do the right offend the core values of left-wing voters more deeply than vice versa? Are the left more emotional about their politics?

Back in 2013, when he was still London mayor, Boris Johnson wrote: “On the whole, right-wingers are prepared to indulge left-wingers on the grounds that they may be wrong and misguided but are still perfectly nice. Lefties, on the other hand, are much more likely to think right-wingers are genuinely evil.”

The idea of the “intolerant left” is so often voiced by right-wingers that it has become a trope – but let’s put the messenger aside and consider the message. Within my own social circle, it certainly seems that those on the left think those on the right are “worse people”. Not evil necessarily, but morally inferior. Less caring, less compassionate, less concerned about the suffering of others and therefore more selfish and more cruel.

Moral and political psychologist Cory Clark says there is little consensus on the psychological differences between those on the left and the right: “My personal assessment is that they are probably quite similar – and dislike one another to similar degrees – though there are very small differences that seem real and replicable.”

To better understand these differences, let’s consider another asymmetry – between a vegetarian and a meat eater. On the one hand, these are dietary choices, two sides of the same coin. But they’re not equivalent. The meat eater could have the vegetarian’s dish (even if he might not enjoy it so much) but the vegetarian wouldn’t eat the meat eater’s dish, because their diet is defined by their opposition to meat. In fact, when they look at the meat, they are likely to perceive harm – whether that be the suffering of the butchered animal or the environmental impacts of the diet. The meat eater might judge the vegetarian’s choice as foolish or impoverished or virtue-signalling, but they are less likely to see harm and to make a moral judgment.

***

In his book The Righteous Mind, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that the left (“liberals” in the US parlance) build their morality on a smaller number of moral foundations. While left-wingers are primarily concerned about care and fairness, the right tend to be motivated by a wider range of ethical considerations, including care and fairness, but also liberty, loyalty, authority and sanctity. He says that the left score higher on questions of care and harm, like “how much would someone have to pay you to kick a dog in the head?” Nobody wants to cause pain to an innocent creature, but Haidt found that conservatives would have to be paid less. Meanwhile, the right score higher on loyalty to their country and respect for authority. They’d be less willing to badmouth their nation on a foreign radio station or stick their finger up at their boss.

In 2012, Haidt led a study to test how well Americans understood each other. More than 2,000 participants answered various moral questions, either as themselves or imagining how others on their own side, or their political opponents, would answer. Haidt writes:

The results were clear and consistent. Moderates and conservatives were most accurate in their predictions. Liberals were the least accurate, especially those who described themselves as “very liberal”. The biggest errors in the whole study came when liberals answered the Care and Fairness questions while pretending to be conservatives. When faced with questions such as “One of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenceless animal”, liberals assumed that conservatives would disagree.

What Haidt found was that liberals don’t understand conservatives as well as conservatives understand liberals. Could this explain why left-wingers in Britain are less inclined to invite a Tory to dinner? As Haidt writes:

The obstacles to empathy are not symmetrical. If the left builds its moral matrices on a smaller number of moral foundations, then there is no foundation used by the left that is not also used by the right. Even though conservatives score slightly lower on measures of empathy and may therefore be less moved by a story about suffering and oppression, they can still recognise that it is awful to be kept in chains.

One critic of Haidt’s moral foundations theory is psychology professor Kurt Gray, who believes that “harm” is the key consideration for moral judgements across the spectrum of political thought. Taking that idea, it’s worth considering which side may perceive more harm in the policies of the other.

Our morality also influences who we feel we are compatible with. In the most personal realm of dating, indicators suggest once again that the left takes political views more to heart. The same YouGov poll found that 28 per cent of Labour voters would not date a Conservative, while 17 per cent of Conservatives would rule out a Labour supporter.

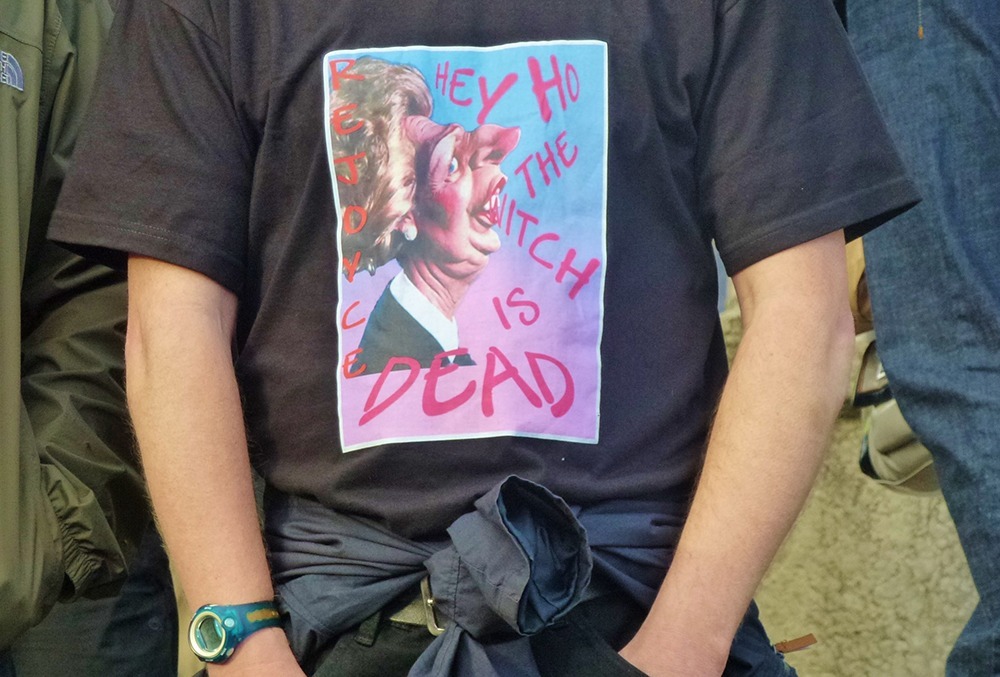

Dating apps like Hinge and OkCupid allow users to filter out people with opposing political views. While there is no clear data available on which demographic is more likely to use this function, the phrase “never kissed a Tory” is such a common brag that it’s become a slogan printed on T-shirts and mugs. Meanwhile, the term “woke-fishing” has recently emerged, with a spate of articles describing the supposed phenomenon of men pretending to be more politically progressive as a seduction technique. A friend of mine recently tweeted her advice to exclusively sleep with socialists “because the politics of selfishism do not make for a satisfactory shag.”

I contacted another friend who swears she would “never kiss a Tory” and asked her to explain her disdain. She believes most Tories to be “greedy and selfish”, telling me, “The right covets wealth and individualism more. There must be something in the Bible about all of that though. Isn’t it one of the seven deadly sins? To covet? Or to be greedy? . . . people know this is instinctively wrong. Some choose to ignore it. Some accept it and feel bad. Some don’t care. But I believe that everyone, instinctively, knows this is the wrong way to conduct your life.”

The religiosity of this language is interesting because several commentators have pointed to the declining role of religion as contributing to our increasing political polarisation. As Conservatism in Britain has become less linked with the Church, perhaps it’s lost a moral force which once helped to counterbalance its devotion to free markets. Similarly, the retreat of religion might have made belonging to the left a replacement faith for many.

***

Guardian journalist Lucy Mangan married a Conservative and has written humorously about her relationship with “Tory Boy”. I was curious to know how they’d conquered the political divide. They’d met at a book launch in their 30s. Tory Boy approached Mangan. The revelation of their political differences came after they’d been dating for a few months.

“I burst into tears the first time he said he was a Tory and a Thatcherite”, she told me. “I can still remember the moment. We were on Beckenham High Street. I think the strength of my feeling probably surprised him.”

Mangan had been raised by parents working in the arts and the NHS, who switched off the television if Margaret Thatcher appeared. So how did she overcome her horror?

“Love the sinner, hate the sin. I said to myself, okay, I’ve believed this thing all my life and now I’ve met this person who I like and understand and am starting to love, so something has to shift. If this is just the tip of an evil iceberg then we’ll have to call it off, but maybe there will be more to it – and of course I discovered that to be a Tory is not to be one thing.”

Being part of a mixed-political couple has made Mangan realise that people are far more tribal than she’d ever expected. Early in the relationship, one of her Guardian colleagues confided that they couldn’t imagine going out with someone who wasn’t a member of the liberal left. Mangan was perplexed. “It’s like Tory Boy often says, there’s nothing more rigid than the liberal orthodoxy.”

Last year the National Theatre staged Simon Woods’ play Hansard, set in 1988, which depicts a Conservative MP arguing with his left-wing wife. Their political conversation is intensely emotional, exposing differences between their worldviews and inner lives. When the wife suggests the cabinet might want to try a trip to the theatre, her husband erupts: “You think your culture makes people empathetic, don’t you? Open-minded. But let me tell you, there is no group of people more narrow-minded than you book readers. Your theatregoers. Appalling people. You try being a member of Margaret Thatcher’s government and standing in the foyer of a theatre. If you want to talk about prejudice. If you want to talk about a lack of empathy.”

***

It may seem ironic that the apparently more empathetic left seem to have hearts of steel when it comes to their political enemies. But as Cory Clark explains, while left-wingers score higher on empathy, it’s “mainly or perhaps only for relatively low-status groups. I suspect the reverse is true for higher status groups and they would not have particular empathy for conservatives.” She says those on the left tend to “perceive women, black people and Muslims as victims and thus they are inclined to treat such groups better than they treat higher status groups. They have a bias in favour of groups they perceive as low status. Conservatives distinguish less by social status and treat groups of higher and lower status more similarly.”

Ed West has written a book addressing his life-long obsession with being a minority conservative in a mostly progressive social milieu. Small Men on the Wrong Side of History expresses his belief, as a young Tory, that he was an anomaly, someone who had developed conservative traits earlier than normal. He assumed that “like baldness or impotence or the other bad things that people get in middle age”, his friends and acquaintances would catch up with his conservatism at some point because “these things just develop at different speeds”.

However, knocking on his 40th birthday, he realised that he was still in the minority amongst his peers, and his Crouch End neighbours, if anything, were drifting further to the left. Even in the 2019 election, which won Boris Johnson a mighty majority, the Tories lost heavily among all age groups under 44. He told me that part of his motivation for writing the book “was trying to convince people that I’m not actually evil.”

He doesn’t always convince. In one anecdote, he describes going out to dinner with fellow Telegraph bloggers James Delingpole, Douglas Murray and Norman Tebbit, “the very man who said ‘get on your bike’ to the unemployed”. They were in an exclusive West End gentleman’s club, eating foie gras (“the cruelest form of food available”), and West felt tempted to toast, “Gentleman, to evil” but he wasn’t sure Lord Tebbit would get the Simpsons reference. In moments like that, does he wonder if he is indeed one of the bad guys? “Oh yes, definitely.”

West highlights the fact that whilst the Tories have political power as the party of government, they are losing cultural power, with the tech industry, universities and schools overwhelmingly dominated by progressives. One of West’s theories for why conservatives might be better able to understand lefties, as in the Haidt experiment, is because Conservatives “will certainly absorb more progressive television and cinema; not because we’re more open-minded (by nature we’re not) but because those are the prevailing cultural noises and so we have no choice, just as any minority has more awareness of and interaction with the majority.”

Talking over Zoom, he acknowledges his own role in feeding the Outrage Industrial Complex. He’d listen to Radio 4 or read the Guardian, get riled up and rant about “leftists” for the Telegraph. His book strikes a more magnanimous tone, and separates his inflammatory professional rhetoric from his personal relationships. He describes sitting in hospital, watching his two-year-old son drawing oxygen from a mask whilst fighting pneumonia, relieved that his daughters are being looked after by good friends who happen to be “solid Labour members and activists who used to knock on doors for their party and have all the social values of the progressive left. They are very good people. I’d trust them to look after my children if we ever died in a plane crash.” He laments the fact that the outrage machine “is dividing thousands of similarly good people in a completely needless way.”

He has some cautionary words for the left: “What is most troubling about the progressive religion is the assumption by some on the left that their side is moral, whereas genuinely moral people should never be comfortable in their righteousness.”

In 1948, on the eve of the creation of the NHS, Labour’s Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan made a speech which claimed Great Britain now had the “moral leadership of the world”. In this very same speech he declared his “deep burning hatred for the Tory party”, calling them “lower than vermin”. His dehumanising language became an icon of tribal politics, in turns celebrated and criticised by his own side. Haidt argues that the left’s lack of understanding of conservatives leads to a conservative advantage at the polls. Rather than stoking contempt, the more productive road might be to grow our curiosity about the moral motivations of political opponents.

We could start by inviting them to dinner. Perhaps there are no nasty parties or inherently nasty people. And if we think there are, maybe the problem is us.

This article is from the New Humanist winter 2020 edition. Subscribe today.