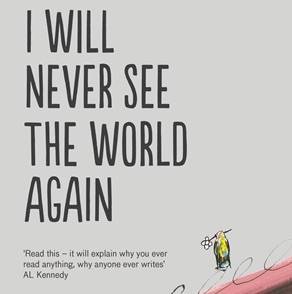

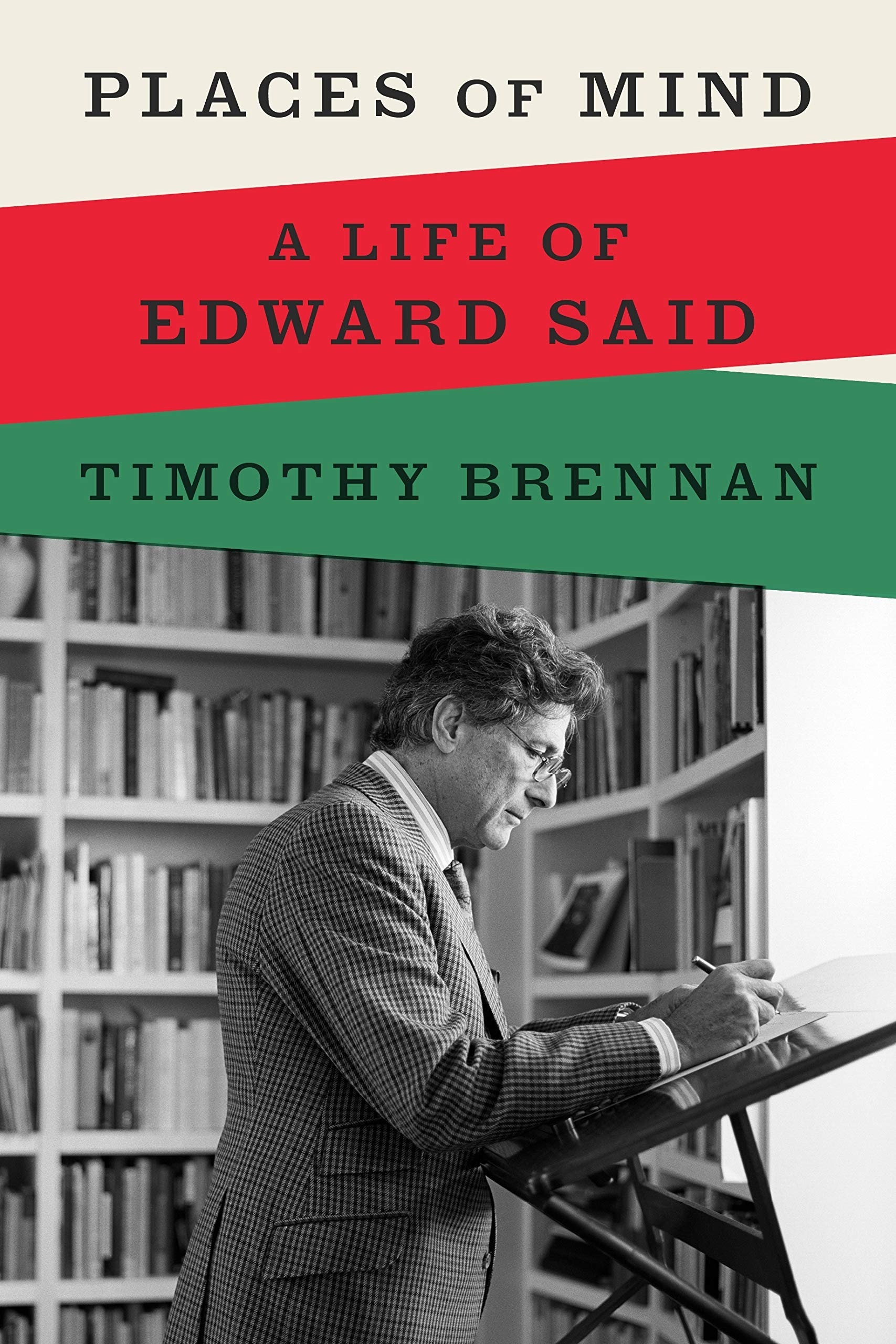

Though books are lifegiving for me, they don’t often move me to tears. But on emerging from Timothy Brennan’s Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said, I found myself sobbing. Having read the biography intensely in a haze of lockdown days, breaking the flow only for exercise, food and sleep, I felt I’d met, fallen in love with and lost Edward Said all in the space of a few days. Such is the depth of the depiction of Said’s life in this careful, tender and profound exploration of a most brilliant life and mind.

It would be difficult for any biographer to make Said’s life seem in any way dull, but there is no doubt that Brennan has an extraordinary capacity to tell a story. Said’s life, in all its brilliance, disappointments, passions and tragedies, appears in vibrant detail on the page. Said’s work holds a deeply important place in my own work as a legal scholar, and it felt like a privilege to learn about the person behind the publications and public persona.

Brennan’s account is far-reaching without ever sacrificing the delicious intimacy which makes biography worth reading. We get to know Said. From the genesis and inspiration of his intellectual and political ideas, to his innermost fears. From his first love, classical music, to his passion for poetry, starting with the Victorian Gerard Manley Hopkins and ending with a newfound love for the Greek poet C. P. Cavafy late in his life. From his struggle with self-doubt, to his love of flattery. From his tireless campaigning for justice, to his guilt at failing to improve the plight of others. From the high demands he sometimes placed on his students, to his affection, sense of humour and generosity. From his hypochondria to his deep hunger for connection.

Said’s principal political concern, the site where he continually returned his mind and invested his passion and energy, was his homeland, Palestine. Brennan dedicates the book to the Palestinian people, mirroring and honouring his tracing of a life dedicated to the very same. Said’s work seeking justice for Palestinians is a better-known aspect of his life, due to the public attention his efforts attracted.

What Brennan draws beautifully for the reader is a rare picture of a young Said, a junior professor trying to make his name through his academic writing, struggling to carve out space in his intellectual work for his politics and his person. These aspects of his background and personality seemed to him inseparable from his intellectual endeavours. As the world’s injustices begged for his attention, often prompting in him feelings of frustration at not doing enough from his comfortable life in New York, Said committed his intellectual writing to showing his colleagues how they might also put their minds to work for progressive political change beyond the academy.

Places of Mind offers a portrayal of Said as a person, continually displaced and exiled as a result of the British Empire’s machinations and its latent and ongoing colonial effects, trying to find both himself and his place in the world. What we glean from Brennan’s narrative is a subtle but powerful sense that Said realised early on in life that one must know oneself, one’s mind and one’s place in the world; not in any fixed or static way, but through profound searching, in order to do the crucial work of reaching others. And it is others Said so desperately wanted to reach, people like him “in their rebellion and in their hope”, to quote his friend and correspondent, the feminist writer Hélène Cixous.

In Said, therefore, one has the sense of a person who knew himself, who never neglected his mind, tending to his emotional life by having therapy throughout adulthood and feeding his soul with poetry and music. Brennan shows us how, by bringing himself as close as possible to himself, Said could become the effective political actor we know him to be. He was not only able to empathise with others, but to arrive at an understanding of the complexity of the human psyche in a world disfigured by colonial violence. He both acknowledged the dangers posed by attachments to victimhood in collective organising, and was willing to engage in the necessarily messy aspects of truly inclusive political struggle.

Said maintained that biological or religious connections to a struggle are not what matters. What matters is learning to identify structures which necessitate the dehumanisation of people, and which have long shaped our psyches and enabled historical events which continue to impact the present. What matters is coming to terms with our own guilt and shame; and feeling our own pain so that we can feel the pain of others; so that we do not hurt others in the way we have been hurt ourselves; so that we do not bite our tongues, but connect with others in the struggle for freedom from oppression. These are lessons that those of us committed to freedom struggles today still need to learn, imbibe and practise.

Said refused to dodge the realities of political struggle, but at the same time dismissed the false trope of “complexity”, all too often mobilised to quell resistance to the oppression of Palestinians. He understood that the Palestinian people are struggling for liberation from colonial oppression, from al-Nakba al-mustamera, or “the ongoing disaster”. He argued that what solidarity asks of all of us is that we speak out and act against oppression in all its forms, that we recognise Palestinians as an empowered, purposive people with desires and voices of their own, engaged in the project of their own liberation.

As a writer, Said was both careful and fearless, remarkably borderless in mind and in the disciplines, sources and theories he leaned upon. Through his writings, Said sought to clarify and distil ideas, to communicate in a manner which opened the way for collective organising that stood a chance of righting wrongs, of making the world – in particular, pained parts of it – more equal and just places to inhabit. Places where people can live and thrive and move without fear.

To Brennan we owe a deep debt of gratitude, for showing us what we still stand to learn from Said in our own connected intellectual, personal and political struggles. And for gifting us this seamlessly composed, rich, moving and heartfelt tale of a life and mind so missed – and so needed in our current political moment.

This article is from the New Humanist autumn 2021 edition. Subscribe today.