I don’t know if you’ve noticed but everything, recently, has been very bad. Granted, the vaccine roll-out has given the pandemic a sort of “end-of-term” vibe – more contagious variants notwithstanding – as we anticipate the return of something like normality. But we have still lost more than a year of our lives to the pandemic. It is an episode we emerge from poorer and weaker, only able to continue, for the most part, as a result of our extraordinary ability to relegate death through illness to the back of our minds. And the pandemic, of course, is far from the worst disaster any of us, in our lifetimes, are likely to face. Perhaps, indeed, the coronavirus lockdowns were just a dry run for the sort of measures that will end up being permanently imposed on us – as the planet, with increasingly rapidity, begins to boil and crack and drown us.

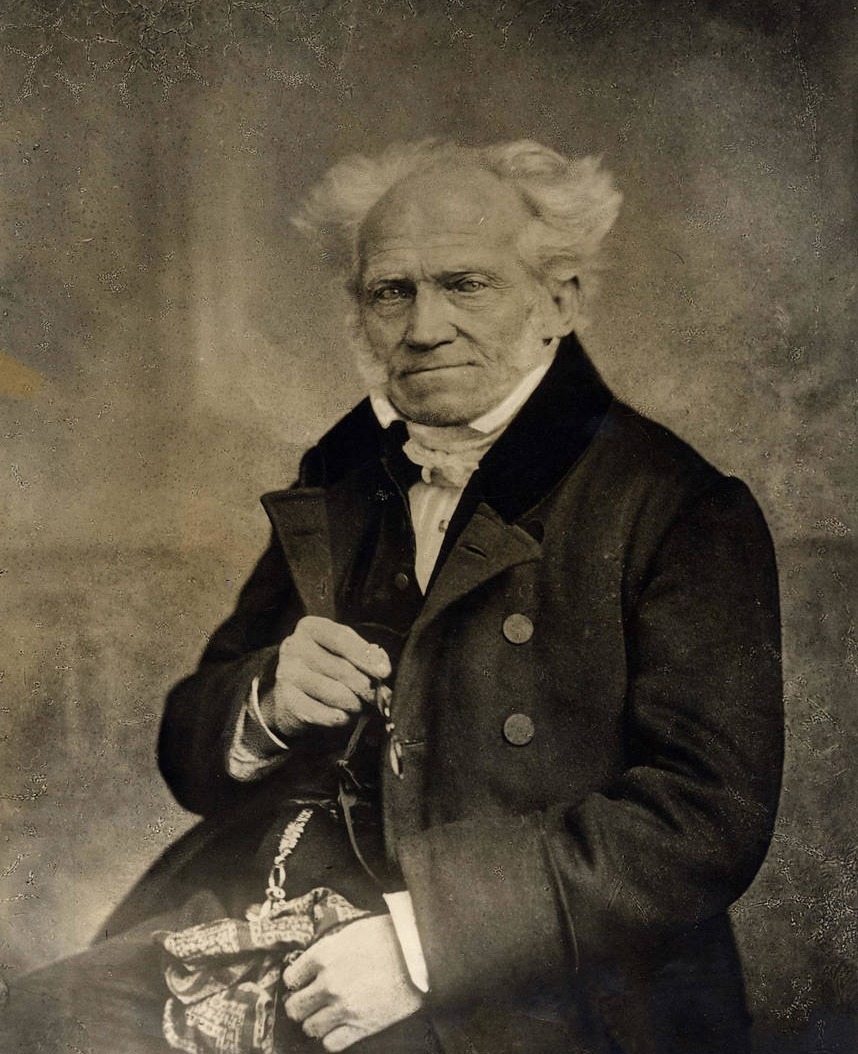

What philosophy could possibly be adequate to such an age of crisis and disaster? On the Suffering of the World, a volume published by Repeater Books last December, might have something like the answer. Edited by the pessimist philosopher Eugene Thacker, the book collects eight of the later essays of Arthur Schopenhauer, the great grumpy old man of the history of thought; the philosophical patron saint of doom and gloom.

In his own most substantial contribution to thinking about how terrible everything is, Infinite Resignation (also published by Repeater, in 2018), Thacker describes pessimism as “a strange philosophy . . . the most adequate, the least helpful”. The pessimist is the one determined to see reality always as it is, not how they would like it to be – to constantly tell both themselves and others how things really are, shorn of any Pollyanna-ish enchantment. But when this happens – when the disaster we exist within is seen, against all our hopes, for what it is – we are left feeling hollow, powerless, resigned; in despair of an existence that, in truth, really doesn’t seem at all worth having. This is the sort of thinker that Schopenhauer was: someone willing to look the problem of our existence in the eye.

Schopenhauer is not an easy thinker to get a clear purchase on. Utterly contemptuous of the academic philosophy of his day, he largely eschewed its conventions, often pitching his work to editors with the promise that it was supposed to appeal more to generalists. The pitch of his invective has a certain visceral appeal, and his willingness to take his cues from “real-world” phenomena, like sex or noisy neighbours, ensures that his is a thought with its feet planted, at least in some way, on the ground. But in truth, Schopenhauer made few concessions to the general reader either: for most of his life, his work barely sold. His essays – even his “popular” ones – often have a rambling, repetitious feel, like being forced to listen to a crotchety old fart drone on and on about something in your general direction. They were typically published as a supplement to The World as Will and Representation. Regarded as his “chief” work, The World as Will and Representation is a sprawling, purportedly systematic monolith, which nowadays one inevitably feels obliged to surmount before attempting any of the rest of his writings, given that they are almost always still published together. One great advantage, then, of On the Suffering of the World is that when you hold it in your hands, you feel relieved of this burden. Here, finally, is a version of Schopenhauer which feels condensed enough to approach. No longer does one have to sacrifice too much of one’s life to find out why it’s not worth living.

As Thacker puts it, in his illuminating introduction to the volume, Schopenhauer is a thinker who spent his life elaborating just one “single thought” – a thought which Thacker identifies as: “I do not live, I am lived.” For Schopenhauer, the individual self of our perceptions is essentially an illusion, belonging to the world as “Representation” – or, how we are obliged to picture things to ourselves. What really exists is “the Will”: an endless, blind, inhuman process of compulsion and desiring, of meaningless creation and destruction. Everything is bad; obviously, empirically bad, as Schopenhauer relates in “On the Vanity and Suffering of Life”, the first essay here and almost certainly the best introduction to his general outlook.

We feel pain, but not painlessness; care, but not freedom from care; fear, but not safety and security. We feel the desire as soon as we feel hunger and thirst; but as soon as it has been satisfied, it is like the mouthful of food which has been taken, and which ceases to exist for our feelings the moment it is swallowed . . . How human beings deal with themselves is seen, for example, in slavery in America, the ultimate object of which is sugar and coffee. However, we need not go so far; to enter at the age of five a cotton-spinning or other factory. . . is to purchase dearly the pleasure of drawing breath. But this is the fate of millions, and many more millions have an analogous fate.

But it also can’t get any better: because the world is bad as a result of the Will which lives us – and because it lives us, we have no autonomy in relation to our desires. We might hate that the world is like this, but we can’t meaningfully want it to be any better. At heart we are all stupid, selfish and hopelessly short-termist. Even the best of us will ultimately acquiesce somehow in exploitation; all of what we think are our decisions will ultimately end in failure and frustration. “As long as our will is the same,” as Schopenhauer puts it, “our world cannot be other than it is."

Schopenhauer's pessimism offers hope

This thought, of course, seems deeply relevant in the age of climate change, when everything we do, in all innocence, to prolong and to enjoy our lives seems bound to intensify the process which is tending towards the destruction of all things; when even the most concerted attempt to stand, saint-like, outside of this process seems likely to prove roughly as effective as an animal caught in a trap trying to escape by tearing at its fur. But for Schopenhauer, even death would be no way out – “death is for the species what sleep is for the individual,” as he liked to put it. Upon our deaths, while we as individuals may be unburdened of the consciousness of our situation, some new individual quite like ourselves will be born again into the same hell, to undergo our fate instead.

And so, reading this volume, I was surprised to find – even within Schopenhauer’s unwaveringly pessimistic vision – the basis for a real sort of hope. This might sound surprising. But in fact, if we take our cues from Thacker’s definition of pessimism, it makes perfect sense. Real hope must be distinguished from mere wishful thinking. It must provide us with a basis for practice, for actually doing something about things, or else all it will amount to is a reason to remain happily, passively, resigned to whatever fate has in store.

Any optimist worth their salt, therefore, must start out as the most deflated pessimist: they must strive to see our situation adequately, for how wretched it actually is. The challenge for hope, then, lies in finding the faith to try and do something about it – to respond to the realisation by doing something other than being immediately hollowed out by despair. In a way, Schopenhauer really does give us the seeds for this sort of hope – even if he has gone out of his way to hide them as deep down as possible in the dirt.

For Schopenhauer, we might not be able to change the Will, but we can do at least one thing other than acquiesce in it: we can strive to deny it. In showing this, he draws on Eastern philosophy and religion, especially Buddhism – but he also cites examples from Christians such as the early Church fathers, or Francis of Assisi. Schopenhauer appears to envisage the process through which one might come to deny the Will along roughly similar lines to the story of the Buddha: through an awareness of the sufferings of the world, one might find oneself decentred from one’s selfish, temporal desires. Having thus come to realise that no good can arise from getting what we want, one is given to submerge one’s desires, to pursue inner peace – although this is a state that Schopenhauer thought could only really be brought about for any one individual if the whole world were to be given peace as well.

In Schopenhauer’s writings, admittedly, this wisdom is offered as a counsel of despair. Something can be hoped for, maybe – but that something is, quite literally, nothing. But now, let’s think about what this “nothing” might look like in practice. Suppose the world were given peace. Must this in fact entail non-existence? If Schopenhauer thinks we should do anything, it is to strive, if even against the whole concept of striving itself, to create a world in which we are all decoupled from our basic selfishness; in which we have the strength to stand in solidarity with the sufferings of others; in which we have both the courage and the knowledge to meaningfully refuse to add to the world’s sum total of pain and exploitation. To live not for ourselves, in short, but for others. To not cling desperately and selfishly to our own lives, but to feel able to embrace the end joyfully, when ultimately faced with our time to go.

Perhaps such a world, full of people like this, would be impossible. Perhaps, given how we are mere puppets of the Will, such a world could never, finally, permanently, be brought about. At any rate it is a utopia that seems to be becoming more, rather than less, alien to us right now. If anything, the pandemic has increased our tendency to live as isolated little consumer-atoms, only able to satisfy our short-term lust for dopamine through the computer screen.

But even in the darkest depths of his pessimism – and despite, I think, anything he understood himself to be doing – Schopenhauer nevertheless manages to give us an idea of how we would need to be re-oriented towards our selves and our world, if we were ever going to try and change things for the better. It is as much for his secret hope as for his bombastic pessimism that Arthur Schopenhauer is a thinker for today.

This article is from the New Humanist autumn 2021 edition. Subscribe today.