As soon as Christina and Jake Hunger brought their new puppy home, they were utterly smitten. Stella was a tiny eight-week-old Catahoula-Blue Heeler cross, with rich, chocolate-coloured fur, bat ears and a white bib. Stella was a highly engaging little dog, almost frantic with delight every time they entered the room, wagging her tail so hard it set her whole body a-wiggle.

Puppies are hard work. There was toilet training, nap times, playtime and lead training. At night, Stella often whimpered until Jake went downstairs to sleep by her bed. But Stella was a quick learner too. Some commands, like “Come”, were easy. They just bent down and patted their knees and Stella would dash right over.

Christina, who works as a speech-language pathologist, was struck by just how precocious her pet was. Sure, Stella was a puppy, but she was also displaying many of the pre-linguistic skills Christina looked for in her nonverbal clients: she maintained eye contact, whined for attention, dropped toys by their feet when she wanted to play, and used gestures to make requests, like pawing at her empty water bowl. Christina started noting down these milestones as she noticed them: already, at two months, Stella was exhibiting over half of the skills a nine-month-old baby might be expected to demonstrate shortly before they begin to say their first words.

It wasn’t the same. Christina knew that. Stella wouldn’t keep passing milestones that would, within months, bring her miraculously into the realm of the verbal the way most infant humans are. Still, it was enough to give her pause.

In her job, Christina works with children with developmental issues, finding ways in which they might communicate their wants through non-normative means. This field, known as “augmented and alternative communication”, or AAC, encompasses many tools and techniques, including sign language and facial expressions, as well as speech-generating devices of the kind used by Stephen Hawking. In AAC, there is no “right” way to communicate, no end goal for clients to aim towards; success is successful communication of intent between two parties, however that’s achieved. Often she uses iPad apps, allowing her clients to press buttons that enunciate words or phrases on their behalf – “More”, “Stop”, “Hungry”, “All done”.

Human devices for canine friends

What she likes most about her job is that her clients often surprise both her and their parents with their hidden abilities. Suddenly, children who had seemed oblivious to much of what was going on around them would seize their device and communicate in unexpected bursts, stringing together words they had never before used or even seemed to understand. Sometimes children who seemed to have plateaued would make huge advances once their device was reprogrammed to offer a better range of vocabulary. In this way, Christina had learned never to underestimate how closely someone else might be listening, even if they seemed inattentive or used unusual body language, their verbal speech non-existent.

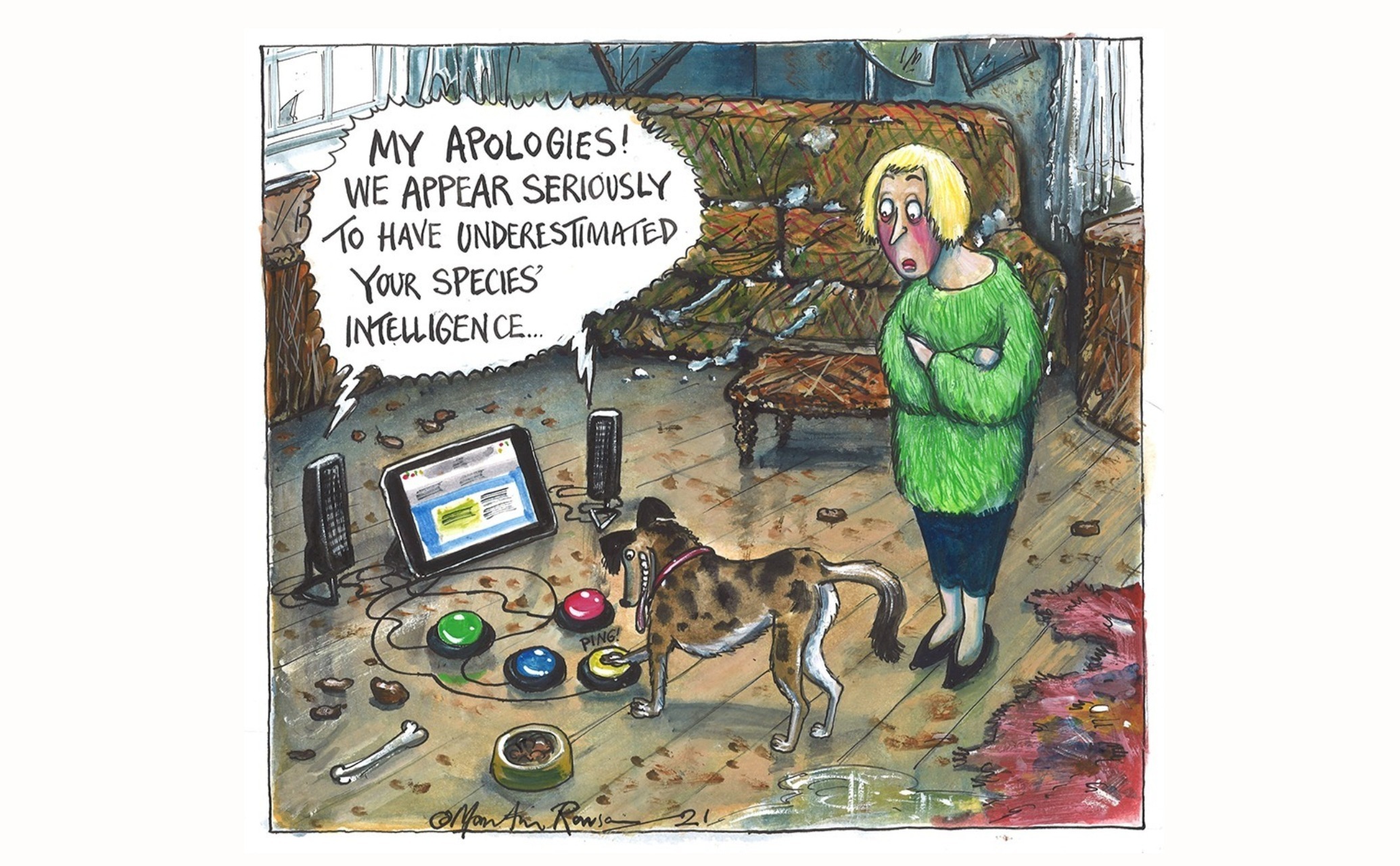

Christina wondered whether Stella could learn to communicate using similar tools. Could a dog use AAC? She didn’t see why not. One evening she found a pack of four “recordable answer buzzers” online – easy-press buttons intended for use during parlour games, but perfect for Stella. They were palm-sized and easily compressible by a paw or a muzzle. When triggered, each button would sound a short audio clip. Christina programmed the first button to announce “Outside”. It would be Stella’s first word.

It took a while for the penny to drop, but after three weeks of Christina and Jake pressing the button with their toe and enunciating the word before opening the door, Stella began to pay it a great deal of attention. Sometimes she would bark at the button, as if willing it to activate itself, or tensely sit by it, waiting for them to press it. Christina recognised this behaviour from the children at work: sometimes a child on the cusp of understanding would take her finger in theirs and use it to press the button on their behalf. It was a good sign: this usually happened very shortly before the child first used the device for themselves.

Sure enough, a few nights later, Jake woke Christina. It had happened. They rushed downstairs. Stella did it again. Outside. Outside. She seemed delighted with herself, and when they opened the door in response she ran in ecstatic loops around the garden. Jake and Christina were elated.

Since that first button push, Stella has gone on to learn around 50 words: nouns, verbs, adjectives. Christina introduced them slowly and thoughtfully, based largely on her own intuition and her experience of working with children. She also tried to offer Stella what speech-language pathologists call “core words” – that is, the words she would use most often. Then, as with the “Outside” button, she and Jake would faithfully model the new words every time a suitable situation arose. They’d press “Water” right before they refilled her bowl. Or “Play” before, during and after a game with a toy.

Stella’s favourites, of course, were “Walk”, “Beach”, “Park”. But she also had “Help”, “Love you”, “Bye”, “Bed”, “Cat”, “Eat”, “No”, “Play”, “Want”. Stella was curious and would press buttons to see what happened next. Christina and Jake would enact what the button suggested, and after dozens or hundreds of reinforcements, Stella learned what to expect. Christina wasn’t sure that Stella understood the words to mean exactly what we use them to mean, but the connotations were similar. “Love you” became associated with cuddles, soft voices, sympathetic attention.

Christina was working purely to satisfy her own curiosity. But Stella’s progress was quick and caught her by surprise. In early interactions, button usage orbited around requests: “Outside” to go to the toilet, “Help” to request assistance with a lost toy. As time went on, Stella began to use the buttons in interesting ways. While watching Christina watering houseplants, she pressed “Water”; when emotionally charged, she tapped buttons repeatedly. She then began to combine words. “Eat no” one evening when they got home past her usual dinner time. Later on, “Come outside”. Further down the line, “Stella want play”.

The limits of a dog’s comprehension

Christina isn’t the first person to explore the limits of a pet dog’s language comprehension. Behavioural psychologist Dr John Pilley once taught the collie Chaser the names of 1,000 toys, and later demonstrated that she understood basic grammar. But Christina’s AAC board meant she could study not only Stella’s comprehension but her capacity for generating language, for two-way communication. The experiment has been successful far beyond what she ever imagined. Throughout, she has documented Stella’s progress online, via her popular Instagram account, @hunger4words, where she has amassed close to 800,000 followers, many of them pet owners keen to try Christina’s methods for themselves.

Among them is Alexis Devine, an artist based in Tacoma, Washington, who in 2019 bought a bouncy, bed-headed Sheepadoodle (an Old English Sheepdog crossed with a Poodle) called Bunny. She used an AAC system and also began with a simple “outside” button by the front door. Alexis copied Christina’s methods. Over a six-month period she modelled new button usage before combining them into a large wooden “keyboard” on the floor. Soon she was contacted by Leo Trottier, a cognitive scientist and computer programmer who offered her the use of a prototype canine AAC device, which grouped buttons by type – activities, objects, places, descriptions – in a modification of the Fitzgerald Key, a system developed in the early 20th century to help deaf children structure sentences.

Since then, Bunny’s progress has been even faster than Stella’s. Videos posted by Alexis, who has seven million followers on TikTok (@whataboutbunny), show more than 90 buttons arranged on neat hexagonal tiles. In one viral clip, Bunny looks in the mirror and appears to experience an existential crisis. “Who this?” she asks. “Bunny”, Alexis replies. Bunny then walks away and stares through the window before returning to press “Help”.

Amusing as the videos are, the researchers need harder data to work from. The history of cross-species communication study has been plagued with controversy. In one famous early example, a horse called Clever Hans appeared to perform calculations on request, tapping his hoof on the ground to answer questions like, “What is three plus four?” Hans would perform when asked both by his owner and by strangers, but it became apparent that he was responding not to the rules of mathematics, but to his questioners’ body language: when he reached the right answer, they would relax, and he would know to stop tapping.

The science of talking animals

Clever Hans’ owner was not a fraudster – he was utterly convinced of his horse’s genius – and Hans also took in a number of contemporary scientists. What the case demonstrates is just how difficult it can be to disentangle animal comprehension from their responses to subtle cues. “The issues of overinterpretation (ie the human interprets the animal signals as more meaningful than they actually are) and cueing (the animal reproducing sequences acquired through extensive learning or simply responding to cues by the human rather than flexibly producing communicative sequences) have long been discussed as some of the main issues of several other animal language studies,” explains Federico Rossano, a cognitive scientist at the University of California, San Diego. He has been studying Bunny’s progress as part of the “They Can Talk” research project, which aims to apply “a rigorous scientific approach to determine whether, and if so, how and how much non-humans are able to express themselves in language-like ways.” Bunny is only one of 3,000 pets taking part in “They Can Talk”, in which Rossano, Trottier and others have been analysing the dogs’ keypad logs and the context in which the buttons are used.

The key requirement for them to be classed as language users, in Rossano’s opinion, is that the dogs must be able to combine and recombine the various words in different contexts – that is, not simply asking “Where dad?”, as Bunny has done when Alexis’ partner goes to work, but also asking “Where mum?” when Alexis leaves, and so on. “If she repeats or slightly modifies sequences when she does not get a response and clearly orients towards the human while producing the button presses, it would appear more likely that she is trying to communicate something.”

Rossano and his team have installed five cameras in Alexis’ house to allow a constant livestream to be beamed to Rossano’s lab. “Having the cameras on Bunny’s board takes some of the pressure off of me feeling like I have to personally record everything,” explains Alexis. It also removes any suspicion that she might be selectively editing their interactions. So far, Rossano says, the data is quite convincing. The “They Can Talk” team is preparing to present their findings to the scientific community. It’s important, he says, to “retain a healthy scientific scepticism”. Nevertheless, “the evidence points pretty clearly towards them [the pets in the study] communicating with the humans while using these devices”.

Alexis too is keen to underline that she does not know exactly how much Bunny understands of their interaction. “I’ve been open about the importance of scepticism, and the difficulty of avoiding implicit bias from the beginning, and thankfully I personally am not tasked with proving or disproving anything. Our journey is about curiosity, connection and exploring the depths of communication with a non-human animal, and I think that’s pretty important regardless of the eventual scientific findings.”

Shaping a dog's mind and body

Dog owners are not unbiased parties when it comes to assessing their own pet’s mental abilities. This much is obvious. I’m a dog owner, and I can tell you this for free. When dog owners speak to one another, we often expound at length upon our pets’ habits and personalities, their likes and dislikes, even their opinions or dreams. Some of these impressions may well be true. It’s also possible, even likely, that we are wrong more often than not.

We project a great deal onto our wordless companions, and pride ourselves in playing a protective, even parental, role in their lives. They offer us clues as to their feelings, moods and wants, but we can never truly know what they are thinking. Maybe that’s for the best: “no small amount of dogs’ winsomeness is the empathy that we can attribute to them as they silently contemplate us,” wrote the cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz, director of the Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, in Inside of a Dog.

Nevertheless, the relationship between dog and human is unusually close thanks to an estimated 11,000 years of domestication. We feed them, care for them and breed them selectively for friendliness and other useful traits. We have shaped almost every attribute of their bodies and minds. They live in our homes and play important roles in many industries. In various ways, dogs have shaped us too.

If any animal was likely to excel at communication with humans, it would be the dog. Yet until now, there has been surprisingly little study of them. Past animal communication researchers have instead opted for gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and even dolphins. But monkeys and apes, for all their human-like characteristics, are notoriously erratic, even aggressive. Dolphins, being water-based, bring myriad logistical problems. Dogs, meanwhile, are domestic companions, unusually easy to train, responsive to human commands and body language, and are often – but not invariably – keen to please. For these reasons, the Soviet space programme, unlike Nasa’s, opted to use dogs in early rocket launches after circus trainers warned them that monkeys were too temperamental to be useful.

Their attentiveness and intelligence is part of what makes dogs so appealing, but our love for them is also part of the reason why it’s so difficult to lay aside scepticism. “It is not the animals who desire to speak and cannot, I suspect; it is that we desire them to talk and cannot effect it,” writes Horowitz. In past interviews, Horowitz has called for research to focus on dogs’ natural modes of communication and behaviour, rather on their capacity to learn or respond to ours. Nevertheless, it’s difficult not to get excited by Bunny and Stella’s conversational prowess, and the small glimmers they offer us as to how canine minds might work.

We may never know if the dogs are using and comprehending human language to mean exactly the same as we do. But if nothing else, it gives us a great deal of insight into our relationship with them as a species, their concerns and their personalities. As for my own dog, I haven’t yet tried to teach her to speak. I very much want to learn her innermost desires, but I suspect she has little interest in communicating with me on my own terms. If she did, I imagine it might closely resemble the one-track conversation of scrappy Bastian, a rescued terrier in New York City (@bastianandbrews), who will scratch the relevant buttons repeatedly until their covers fly off. “Hungry hungry hungry hungry,” he says. “food food food food treat treat treat treat food food food.”

Still, who can blame him? I think I can relate.

This piece is from the New Humanist winter 2021 edition. Subscribe today.