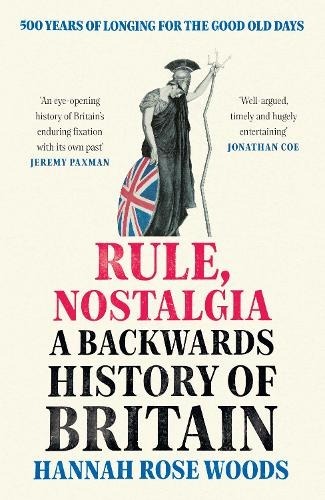

Rule, Nostalgia: A Backwards History Of Britain (WH Allen) by Hannah Rose Woods

Most people, in most places, prefer to think well of their country – not just what it is but what it has been. This is a reasonable enough desire, but often manifests itself in lachrymose revisionism, with corrosive effects upon the present. Amid Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s nine-volume blank verse epic Aurora Leigh is a fret to the effect that “Every age/Appears to the souls who live in it . . . most unheroic.” Barrett Browning wrote that line in 1856, at a time when Britain ruled as far afield as Hong Kong and New Zealand. The British had just triumphed in the Crimean War – but not before the Light Brigade’s vainglorious charge at Balaclava, a heroic failure that would be burnished and treasured for decades to come. There really is no pleasing some people.

Hannah Rose Woods cites Barrett Browning’s mournful observation at about the mid-point of a thoughtful, gently provocative and bleakly witty survey of Britain’s long grumble that “things are not what they once were” (a subsidiary subtitle of the book is “500 Years Of Longing For The Good Old Days”). Woods tells the story backwards, beginning with the near-present. The first chapter – “Keep Calm And Take Back Control” – pulls the threads of post-Brexit Britain’s bizarre paranoias about Europe until they reach the first election win of Margaret Thatcher in 1979. The last chapter winds back from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 to the 16th century, fading on the spectacle of theatre audiences revelling in Shakespeare’s Henry V, itself a nostalgic rendering of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

Nostalgia is not a British peculiarity, of course. The populist tantrums hurled by the spoilt, complacent citizens of many democracies in recent years have all been underpinned by a yearning for an idealised past. Implicit in the Trumpist slogan “Make America Great Again” is the idea that things in the United States were better then than they are now (as indeed they may well have been for entitled white people who couldn’t be bothered reading books or newspapers). “This is not,” Woods writes in the introduction, “a book about whether people in Britain have fallen victim to a nostalgia trap in a way that other people might have escaped from.”

Instead, as it works backwards through the centuries, Rule, Nostalgia amounts to a passionately argued plea to Woods’ fellow citizens to see their history as it was, rather than what they imagined it might have been. And though her contention is that nostalgia has been a fact of British life since approximately day two of British history, her decision to start the book in the present day is justified by the quantity of nostalgia being trafficked in the here and now. She refers, for example, to the absurd speech given at the 2017 Conservative Party conference by Jacob Rees-Mogg, himself a nostalgic confection, forever comporting himself like an otherwise unemployable actor guiding tour groups around a kitsch recreation of Chez Havisham. The MP squawked of Brexit that “It’s Waterloo! It’s Agincourt! It’s Crecy! We win all of these things!”

When Britain’s public conversation has descended to such fatuity, any reminder that British history is not an incessant parade of righteous triumph is valuable. Woods provides this, but does so with affection as well as knowledge. Rule, Nostalgia is radiant with an enthusiast’s passion for their subject, and makes a convincing case that Britain’s history is sufficiently weird, fascinating and marvellous, without rewriting it into comforting fables, or wielding it as a hopelessly inaccurate yardstick for measuring the present.

This piece is from the New Humanist autumn 2022 edition. Subscribe here.