Sleep is a hot topic these days. Popular science books promise to uncover why we do it at all, while exploring its importance for a healthy life. Self-help manuals seek to teach the art of sleeping well amidst the stresses of modern life. Wearable devices and mobile apps monitor quality and quantity, nudging users to make adjustments to their bedtime routines. Meanwhile, last summer’s heatwave produced endless variations of top tips for ensuring the right amount of sleep in sweltering temperatures.

These examples do not just point to an increased curiosity for an activity that, after all, makes up a third of our lives. Rather, they suggest a certain anxiety around sleep and a desire to master it. The key goal of Matthew Walker’s international bestseller Why We Sleep, for instance, was to demonstrate the importance of sleep to a society that, he argues, all too often neglects it with disastrous consequences for our health. That was published in 2018. Since then, the idea that our society may be experiencing a “sleep crisis” has become more popular, with reports that people’s sleep debt – namely, the difference between the amount of sleep they need and the amount they actually get – has been rising in recent years.

This concern over the number of hours people sleep, or fail to, has led to growing attempts at regimenting and optimising the night-time, be it through sleep-tracking, sleep-hygiene routines and sleep hacks, relaxation apps, or other assorted gadgets, from smart mattresses to smart light systems. Underlying these attempts is the sense that sleep should be harnessed. As one popular sleep-tracking wearable puts it: “Sleep more. Achieve more.”

In this landscape, Alice Vernon’s new book Night Terrors: Troubled Sleep and the Stories We Tell About It offers a breath of fresh air. Vernon highlights the need to widen our conversations around sleep beyond the anxious focus on maximising the number of hours we spend doing it. Her stories of troubled sleep purposefully steer well clear of the subject of insomnia – a condition that has been the core theme of a recent boom of memoirs, such as Marina Benjamin’s Insomnia (2018) and Samantha Harvey’s The Shapeless Unease: A Year of Not Sleeping (2020).

Instead, Vernon turns her attention to sleep disorders like somnambulism (sleepwalking), sleep paralysis and hallucinations. And of course, the titular night terrors: terrifying dreams which will typically cause the sleeper to scream and bolt out of bed, and which, unlike nightmares, the sleeper will typically not remember upon waking. Through exploration of these phenomena, Night Terrors invites us to embrace the weirdness of sleep and to look more closely at aspects of our night lives that often thwart any attempts at control.

Gateway to consciousness

The book is many things at once: a vivid memoir of Vernon’s own experiences of troubled sleep, an accessible account of the science of the sleep disorders that are collectively known as parasomnias, and a rich cultural history of how these disorders have been interpreted and represented throughout the centuries. Such a fluid approach feels fitting. Sleep is both a subject of scientific research, about which we know more and more, and a phenomenon that can still elude our rationality and even fill us with utter horror, producing endless theories and fuelling the imagination. In skillfully weaving the strands of the book together, Vernon perfectly captures the liminal status of sleep.

Parasomnias, the focus of Night Terrors, are undesirable movements, perceptions, behaviours and emotions that arise as the brain transitions between REM (rapid eye movement) sleep – the stage when dreams tend to occur – non-REM sleep and wakefulness. These disorders, Vernon tells us, are quite common: 70 per cent of people experience a parasomnia at least once over the course of their life, typically sleep-talking or nightmares. She points out that the real percentage is probably even higher, given that a feature of some sleep disorders is that, upon waking, people do not have any recollection of what they have experienced during the night. What is more, people may be reluctant to talk about them: there is still a certain stigma attached to these “sleep demons”, which for centuries were explained away through the supernatural, or seen as a mark of insanity.

Night Terrors argues that we need to talk more about parasomnias, both to combat this stigma and to give voice to what these disorders tell us about ourselves. In Vernon’s impassioned writing, parasomnias emerge as an important gateway into different forms of consciousness, both individual and collective – which we ignore at our peril. “Our little upheavals or our major traumas”, she writes, “can all come back through the trapdoor of sleep, so to ignore this part of ourselves can mean that we never really face what our dreams are telling us.”

The reader’s journey starts with the very first parasomnia that Vernon experienced as a child: sleepwalking. We then move on to hypnopompic hallucinations – primarily visual hallucinations that manifest moments after waking up; think spiders scuttling on your pillow. Later on, we explore sleep paralysis, night terrors and, finally, dreams and nightmares.

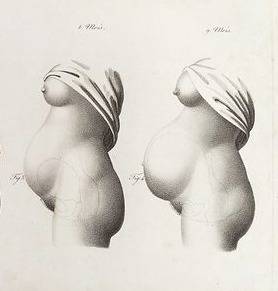

A thread running through the book is the story of Vernon’s claustrophobic and manipulative relationship with a former teacher, whom she calls Meredith after mara, “an Old Norse word for a witch who would lie on people’s chests and try to suffocate them”. The mara is what we now know to be sleep paralysis, a parasomnia where the body’s inability to move – preventing us from acting out our dreams and hurting ourselves or the people we sleep with – continues after waking up. The person is lying down, fully awake and conscious, and yet entirely unable to move. Even screaming is impossible.

This is a paradoxical and terrifying situation. In response, the brain can conjure up images of sinister figures looming over the sleeper and weighing them down, to explain the sensation of being pinned to the bed and the feeling of pressure on one’s chest and limbs. While Meredith’s oppressive hold on teenage Vernon is linked to a number of Vernon’s experiences of parasomnias, it is most clearly reflected in the sleep paralysis “demons” that populate her nights later on in her life. Vernon describes how, during sleep paralysis, she feels “crushed under the intense stare of Meredith, under her hands and her sharp nails”.

Sleep paralysis, nightmares and dreams

The chapter on sleep paralysis is among the most engrossing. Beyond exploring the science of this parasomnia and providing memoiristic insights into the trauma that lies at the root of her own experiences, Vernon traces how the disorder has shaped paranoid beliefs across the ages. Looking at the historical records of the 17th-century Salem witch trials, for instance, Vernon learns how experiences of sleep paralysis generated several accusations of witchcraft in the trials. More recently, this parasomnia is thought to be the origin of many reports of alien abductions that supposedly happened at night and were accompanied by a peculiar heavy feeling. “What we see during sleep paralysis,” Vernon explains, “has changed significantly as our cultural depiction of monsters has shifted”.

Parasomnias seem to have always played a role in the cultural imagination. Night Terrors is peppered throughout with insightful readings of historical paintings and texts, many of which are iconic, that draw on these strange and powerful phenomena. Vernon’s reflections on Dracula, the protagonist of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, note that he causes paralysis, somnambulism and night terrors in his victims. He was not just a vampire, she concludes, but “every parasomnia combined in the figure of a folkloric monster”. Just as vampires straddle life and death so do parasomnias – during these sleep disorders “the waking, rational self is effectively ‘dead’.” The book goes on to illustrate how many of our famous writers, from Robert Louis Stevenson to Shirley Jackson, drew inspiration for their fiction from their real-life experiences of various parasomnias.

But it’s not just that parasomnias can inspire creativity or that culture can help shed light on these strange sleep phenomena. Rather, Vernon argues that storytelling can have therapeutic potential when it comes to sleep. She points to the DreamsID project, a collaboration between sleep scientist Mark Blagrove and artist Julia Lockheart, in which participants share their dreams, nightmares and other parasomnias, whose findings seem to suggest that the process encourages empathy. Imagery rehearsal therapy is also discussed: a cognitive-behavioural treatment for reducing the number and intensity of parasomnias, where the patient is helped to reimagine their nightmares with different, less terrifying outcomes. There are also attempts being made to harness lucid dreaming, which allows people to be aware that they are sleeping and therefore lets them direct their own dreams.

There is something deeply liberating about Night Terrors’ invitation to encounter sleep on its own terms, in all its weirdness and darkness. As Vernon writes, “sleep isn’t just about the number of hours, [or] the time it takes to nod off . . . Sleep is about stories. It’s about monsters, and ghosts, desires, aggression, trauma and anxiety, health, creativity, and the state of our inner lives.” Her book is a powerful reminder of what we miss when we think of sleep merely as something to master, in order that we might be more productive in the day.

Alice Vernon’s “Night Terrors: Troubled Sleep and the Stories We Tell About It” is published by Icon.

This piece is from the New Humanist spring 2023 edition. Subscribe here.