In his book, The Cap: The Price of a Life, Roman Frister recalls how, as a 16 year-old prisoner in an Auschwitz labour camp, he was raped by a senior inmate. To conceal this misdemeanour, the higher-ranking prisoner stole his victim's cap. This was a death sentence for the boy, who would be shot at roll call for displaying an incomplete uniform. Determined to survive this calamity, Frister exchanged his fate with a sleeping fellow inmate by stealing his unknown comrade's cap. His most memorable emotion, when the shot rang out at morning parade, was feeling "delighted to be alive."

Another similar story: the Russian writer and poet, Varlam Shalamov, spent 17 years in Kolyma, a gulag in northeastern Siberia where as many as three million prisoners met their deaths. Contrary to the view that hardship elicits in humans sentiments of solidarity, neither friendship nor sympathy appears to have survived the deadly conditions of Kolyma. With the human spirit all but extinguished, even that final assertion of human sovereignty the taking of one's life eluded the reach of the prisoners. "There are times," Shalamov later recalled, "when a man has to hurry so as not to lose his will to die."

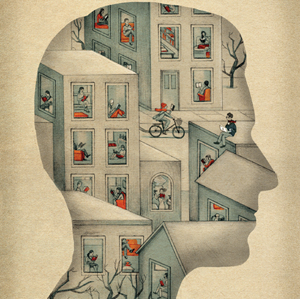

These two brief accounts of degraded life form the centrepiece of John Gray's Straw Dogs, which is a provocative rejection of the philosophical principles of humanism. Central to humanism is the belief that we as a species are uniquely capable of determining our own destiny, of exercising choice and free will, and of achieving collective progress in the historical fulfilment of this capability. For Gray, as the testimonies of Frister and Shalamov appear to bear out, this belief in the irreducible moral freedom of human beings is an illusion, and what really raises human beings above their natural competitors is their unrivalled capacity for self-deception. The human subject, conceived as a unitary self capable of autonomous action and meaningful moral judgement, is one such fiction with which we have deceived ourselves. "The life of each of us is a chapter of accidents," Gray claims, and we are no less predisposed to genocide than we are to art, medicine or prayer.

Gray believes that "free will is a trick of perspective," an illusion that rests on the flawed notion that there is "an inner person directing our behaviour." Curiously enough, this observation is consistent with the philosophy of a leading figure in post-war humanism, Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre also argued, in his first philosophical treatise, that "there is no actor standing behind what we do." Yet Sartre is well-known as the twentieth century philosopher of freedom, as the man who, in his 1945 lecture 'L'Existentialisme est un humanisme', proclaimed that "there is no determinism," that "man is free, man is freedom." This discrepancy suggests Gray's reasoning may not necessarily lead to an anti-humanist conclusion.

Sartre describes human consciousness as a perpetual beginning, an 'impersonal spontaneity' with no determinate content or progenitor. In our everyday dealings with the world, there is, as Gray rightly observes, no antecedent 'I' directing our behaviour. As Sartre explains, there is only consciousness of things to which we have attributed attractive and repulsive qualities. In typing on the keyboard it is not I who commands the fingers so much as the words which, demanded in turn by the deficient space that precedes them, call my fingers forth. In Being and Nothingness Sartre similarly describes how "the man who is angry sees on the face of his opponent the objective quality of asking for a punch in the nose." Sartre is describing here how our original engagement with the world is always conducted in a way which spontaneously denies the role we play in projecting onto our surroundings the demands to which our actions seem an irresistible response.

Humans possess the unique capacity to make themselves the object of their own consciousness, however. By reflecting on our own conduct, we break this magical trance and are forced to choose between perpetuating or refraining from the course of action we discover ourselves in. With this choice comes the first realisation of our freedom.

For Sartre, then, it is precisely the absence of an "inner person directing our behaviour" which is the source of our freedom, for such a governing figure would be fashioned by all the accidents of history, culture and biology which Gray believes are the real determinants of human life. This does not mean that Sartre dismisses all factual influences on human freedom. We discover our freedom in situations which we have not chosen, cannot choose to replace with others, and which we therefore have to assume as the foundation of our choices. We do not exist first, as discrete autonomous entities, then impose our chosen values on the world. Rather, we are always already engaged in the world, and we must make our choices on this basis. Our class position, geographical location, sex, age, ethnic background, physical constitution and so on, predetermine the range of possibilities available to us, though their precise meaning as objects of fear, indifference, empowerment, constraint is always revealed by the ultimate choice we make ourselves, by the person we intend to be.

So for Sartre, as for Gray, much of human life is lived in a state of self-deception. For Gray, it is the illusion of moral freedom which deceives us. For Sartre, on the other hand, it is the denial of freedom which is the deception. Although Sartre describes this primary form of deception as inseparable from everyday consciousness, or the 'natural attitude', he also refers to a more pernicious and wilful form of self-deception, which he calls 'bad faith'. Bad faith occurs when, having been awakened to the reality of the human condition, we attempt to connive with the natural attitude, to conceal from ourselves the freedom which our reflective awareness has uncovered.

The many vivid phenomenological descriptions of bad faith contained in Sartre's work can be divided into two different forms of existential flight. One is the self-denial of my freedom, the pretence that I am fully determined by my situation or context: by my role, social position, inherited values, past behaviour, my body, and my identity in the eyes of others. The other form of bad faith is the disavowal not of my freedom as such, but of its factual context. This is the pretence that I am not bound by my situation, that I can remain unengaged when my body is being used by another for pleasure, that I am untouched by my gender, class or skin colour, or that I can live untainted by a malign and violent world. In a spirit of cynicism, irony or indifference, I may pretend that my utterances and actions are devoid of personal commitment, and that all my actions are rehearsals or substitutes for the real thing.

Implicit in Sartre's discussion of bad faith is an ethical injunction which obliges human beings to recognise their freedom and assume responsibility for their actions. How one might convert the insights of Sartre's existentialism into a guide for action, however, is not at all obvious. Sartre, like Gray, sees moral rules as social constructs, and slavish adherence to such rules as a form of bad faith. Moral authenticity, for Sartre, appears to be a quality of consciousness rather than the characteristic of an act. Hence the concluding passages of Being and Nothingness, where Sartre claims that "all human activities are equivalent", and "it amounts to the same thing whether one gets drunk alone or is a leader of nations."

A more satisfactory account of the relationship between human freedom and values can be found in André Gorz's Fondements Pour Une Morale, a book which reworks Sartre's ontology in order to show that we live on several different planes of existence, each corresponding to a particular set of values. We have a biological existence, through which we experience the vital values of creature comforts, physical ease, agreeableness, adaptability and corporeal pleasures. We also exist as conscious, perceptual beings, from which arises the aesthetic values of irony and play, of the imaginative recreation of the material world, of religious worship, artistic contemplation, and poetic reverie. Finally, we exist as agents of material change, to which correspond the ethical values of liberating activity, of moral engagement with injustice and the suffering of others.

Gorz's argument is that these three sets of values, and the actions which pertain to them, are not morally equivalent. Though each is a source of human flourishing, they also form a hierarchy, the ascension of which requires an increasing intensity of consciousness, and a greater grasp of one's freedom. Vital values, for example, imply a slackening of consciousness, a thickening of thought in favour of a sensory relation to the object and its material qualities. Aesthetic values, on the other hand, are a celebration of mind over matter, a refusal to yield to the brute presence of the given, the triumph of imagination, anticipation and longing, over the world of things. Ethical values, finally, imply a consciousness prepared to compromise with the world in order to change it for the better.

From this richer vein of existential phenomenology, two rejoinders to John Gray's dystopianism can be elicited. First of all, our literary heritage provides abundant evidence of how, even when their freedom is degraded and denied, people resist absolute dehumanisation and rise above their animal-like existence by means of fantasy and dreaming, by surreptitious writing, and by other expressions of aesthetic consciousness. Read, for example, Brian Keenan's rapturous contemplation of the first bowl of fruit brought to his Beirut cell, and his refusal to subordinate the appetite of his imagination to his more primitive need for physical nourishment. Recall the fact that, like many other camp survivors, Roman Frister and Varlam Shalamov felt sufficient defiance of their mortifying experiences to want to turn them into works of literature. Even though the experiences they recount are characterised by a suffering so implacable, as Gray describes it, that it "cannot be told", the survivors were determined to tell their stories, and thus to find meaning in the fact that, when you strip human beings of their society and culture, nothing meaningful remains.

The second conclusion we can draw is that Gray's opposition to the notion of historical moral progress poses no serious challenge to existential humanism. For existentialism defines the human condition as a perpetual beginning, an unfinished finality which, persisting in the depths of our wretchedness as in the heights of our glory, can never be superseded. Since to be human is to be never fully oneself, moral sincerity is a goal we are destined to fall short of. Hence Zygmunt Bauman's felicitous formulation: "one can recognise a moral person by their never quenched dissatisfaction with their moral performance."