As someone who has turned his back on British higher education, I've watched the recent goingson in the British university sector with an air of amused concern. I'm concerned because what we have been witnessing the row over funding, the tortuous negotiations over 'variability', the establishment of an Office of Fair Access, the feats of verbal contortion aimed at convincing us that 'diversity' is an essential component of a highquality university education, have all the hallmarks of some very secondrate fiddling while Rome burns.

I'm amused (in an admittedly perverse sort of way) because all of this and all of the underlying financial and ultimately managerial weaknesses and total failures of leadership which led to it was avoidable. Every bit of it.

I'm also concerned, because it remains as true today as it was when whoeveritwas thought of the phrase 'topup fees' that the ultimate problems facing British higher education remain unacknowledged, and therefore unresolved. Topup fees will solve nothing.

Everyone agrees that the Higher Education sector is grossly underfunded. Our best institutions need a great deal more money than will be provided by their ability to charge £3,000 per annum per student if they are to maintain some reasonable parity with their American peers. They probably need to charge between £12,000 and £15,000 per annum. This money can only come from taxpayers and/or students and/or alumni.

If it came, entirely or substantially, from taxpayers we would find ourselves in a situation in which the taxes paid by those whose children did not benefit from higher education would subsidise the higher education of those who did. Or, to put it crudely but not unfairly, the less well off would subsidise everyone from the reasonably welltodo to what I believe are termed the 'filthy rich'.

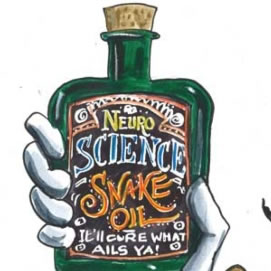

The money some of it at any rate could come from alumni, and from the corporate sector. We do not have in this country a culture of corporate giving; the present tax regime does not encourage it. We could foster such a culture. But the present senior management of our universities and colleges does not want us to go down that road. Universities UK has actually rejected the idea of reform of the tax system, alleging that money which now goes to other charities might be diverted to the Higher Education sector instead. Behind this astonishing shortsightedness there lurks a culture of fear bolstered by a widespread drug addiction.

Put simply, ViceChancellors are hooked on the drug of government money. It's regular income. They don't have to work hard in order to get it. And they are most of them more than happy to do whatever the government of the day wants in order to guarantee the flow of funding.

My present university (which at 950 students is larger than the University of Buckingham), situated in London's West End, charges around £12,000 per annum. We manage to attract British students currently around 60 of them, by no means all from wealthy backgrounds. That's not so astonishing when you consider that because we are open virtually all hours (we have five terms a year) you can do a Bachelor's degree in a little over two years. Class sizes are small. We give a high level of individual customer care. And in most of our programmes you'll get both a British and an American qualification. As you absorb all of this let me remind you that a report in the Sunday Times of 18 January 2004 drew attention to the way in which bright British students are being creamed off by American Ivy League institutions, where tuition fees are high but class sizes are small. People will always be prepared to pay for a quality product.

Just before Christmas I found myself in a room full of senior highereducation managers, explaining how we operate. "What's it like to be a top manager in a feepaying university?" I was asked. And I told them.

In a Higher Education Institute in which the students, or their parents, really do pay substantial fees, there is a degree of personal accountability expected at the top which is quite unknown in most British universities. Students really are customers. They expect a high level of personal attention. After all, they, or their parents, are paying your salary. A student who has a problem say with the way in which a module is being taught will think nothing of presenting her/himself at the door of the Senior VicePresident. This means that the Senior VicePresident (to say nothing of the President) had better know all about this module: how it's taught; who teaches it; how it's assessed.

How many ViceChancellors here, I wonder, know the inner workings of every module taught in their institution?

As I described this scenario my audience of senior highereducation managers grew ever more uneasy. If this was what an authentic feepaying environment looked like, they wanted nothing to do with it. And as they made their unease obvious, I recalled an incident a decade or so ago, when I had led a team of government inspectors looking at a history programme in a 'modern' university. There was nothing scandalously wrong with the programme, but it was certainly not high quality. And at the customary 'feedback' at the end of the visit I told the ViceChancellor so. "Geoffrey", he said to me, "I've learnt more about my history department from your expert feedback than I ever knew before." What the flipping heck had he been doing with his time, then?

Let us now turn to the equally vexed issues of quality and standards.

Only a halfwit would accept that academic standards are the same in all British universities, and that the quality of the educational experience of students at those universities is even broadly comparable between one institution and the next. The fact that a lot of universities scored highly in the now thoroughly discredited Teaching Quality Assessment (TQA) exercise means nothing, except that a lot of universities, colleges of Higher Education and even FE colleges learnt to play a merry game with the entire assessment process (as Ron Dearing warned at the time, though noone in government took any notice of him). In any case, all that a perfect TQA score of 24 points out of 24 meant was that you were judged to have reached the aims and objectives you had set for yourself.

As Pro ViceChancellor for Quality & Standards at Middlesex University I laid it on the line to those in charge of drafting selfstudy documents which formed the basis of every TQA: on no account set an aim or objective for yourself which you are not absolutely certain you can demonstrate you've reached.

An independent investigation commissioned by the English Funding Council reported in 2000 that the combined demands of the QAA upon the sector amounted to £40 million per annum; a single QAA inspection visit cost as much as £250,000. Even the DfEE had to concede that there were far better uses to which this money could have been put.

Opponents of 'variable' topup fees (allowing individual institutions to set their fees within an overall cap) have tried to hoodwink us into thinking that the introduction of the marketplace into HE would be 'a bad thing'. I have news for them. Firstly, in the world of postgraduate awards (for instance the lucrative MBA market) a healthy marketplace has existed for a long time, because universities have always been able to charge what the market will bear. Secondly, as the MBA example shows, and as the American system proves, the marketplace soon sorts out the excellent from the good and the good from the bad.

Whatever we think of the government's ambition to get 50 per cent of 18year olds into HE, the way to make certain that bright students from poorer backgrounds are not disadvantaged is to offer scholarships and generous financialaid packages (grants and loans) to them. These are important issues, which the topup debate has thoroughly obscured, but they are quite separate from that of empowering British universities to charge realistically for the products they sell and the services they provide.

The inroads made by the state into the articulation and mediation of academic standards have amounted to a shameful scandal a story of betrayal from within the academy. Hooked on the drug of taxpayers' money, the leadership of our highereducation institutions (with a few honourable exceptions) happily accepted the cash in return for control of standards and, before long, even the very definition of standards.

For the heads of the expolytechnics this was less of a wrench since they had always seen themselves primarily as managers of nonautonomous governmental agencies, part of the nation's machinery of economic and industrial development. Perhaps, therefore, we should never have expected better of them.

The real worm at the heart of the bud was the 'old' university sector. If the leadership of these institutions had had any guts it would have told the government successive governments of various political hues to keep away. It did not. On the contrary, this leadership actively assisted in the undermining by Whitehall of the universities' financial freedoms and academic status.

Stifled by the apparatus and ordered about by the apparatchiks of central government, the British university system is no longer a worldbeater. Oxford, Cambridge and a few others have some international excellence, it is true. But the endowments at the disposal of these seats of learning are a fraction of those enjoyed by Harvard, Yale, Princeton and other towering American academies. To the braindrain of faculty we will soon see added the braindrain of students.

Professor Geoffrey Alderman, Senior VicePresident of American InterContinental University London, writes in a personal capacity.