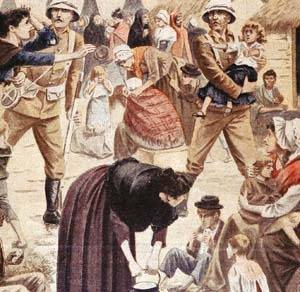

"They hang the man and flog the woman

That steal the goose from off the common,

But let the greater villain loose

That steals the common from the goose"

English folk poem, ca. 1764 Before Greg Dyke departed from the BBC over the Hutton inquiry he left a time bomb ticking deep down in the corporation's archives. If all goes according to plan, it will explode this autumn, ignite a new age of creativity in Britain and cause chain reactions around the world that will wreak havoc among the broadcasting establishment. A small band of radical professors, students, and guerrilla artists even hope it will reach a critical mass that will topple what they regard as an authoritarian regime of philistine bean counters.

On the face of it the plan is innocent. The BBC is merely proposing to open up its programme archives to the public, allowing access to hundreds of thousands of hours of radio and television broadcasting free over the Internet. What makes this move so explosive is the innocuoussounding 'Creative Commons' licence that will accompany the material.

Creative Commons is the brainchild of cyberlaw and intellectual property experts in the United States. They were seeking to establish a legal framework that would be more flexible than copyright, while ensuring that artists, musicians and writers remained in control of their work. Under the licence they devised, noncommercial use is free, as well as in some cases permitting the material to be incorporated into other people's work. Think of it as allowing free educational copies, remixes and collages to be made without first having to seek permission from the creator.

The motivation to do this came as a result of ever stricter copyright enforcement by big business in the last few years. Take the example of University of Pennsylvania professor Joseph Turow, who had to pay around $17,000 in fees and royalties for a total of three minutes of video clips used in a multimedia CD for medical students. Or the elaborate request received by this magazine recently from a teaching institution in Arizona asking for permission to make 38 student photocopies of an article published over 50 years ago. In many cases the sheer amount of work involved in researching copyright and attempting to gain permission is too much for public institutions or private individuals. As a result they resort to selfcensorship rather than risk expensive lawsuits.

Universities across North America and Western Europe discovered just how expensive these lawsuits can be when record companies began suing students and staff who used the Internet to swap music without paying. The companies demanded up to $150,000 per copied track that's over a million dollars per album. Needless to say those affected have been settling for significantly smaller sums out of court rather than face bankruptcy for copyright infringement.

Meanwhile, new laws are being introduced in Europe and the US that will allow the assets of suspected copyright infringers to be seized with little or no evidence. Users complain that such draconian measures are over the top: that there is no serious evidence to prove song swapping is damaging shop sales. Instead, they argue, companies are alienating music fans, who have been sharing their favourite tracks for years on tape and CD anyway.

The industry counters that the advent of the Internet has led to piracy on a scale not seen before, and that musicians will ultimately suffer if record companies lose revenue. This appeal to the fans' love of music is echoed by bestselling artists like Madonna and Elton John, and companies such as CocaCola and Apple Computer who have started providing legal download services.

In pious tones, the head of Apple announced at the recent launch of the company's legal music download site iTunes that customers would embrace it because "it's not stealing, it's good karma". Analysts predict that iTunes will make millions of pounds profit for Apple while providing a service that is available for free elsewhere. Hollywood studios too are gearing up for a battle with Internet users: having lost round one over the video cassette recorder (VCR) in the early 1980s, they are now fighting tooth and nail to stop unauthorised copying of their films.

Small bands, meanwhile, are celebrating the fact that the music industry's monopoly over the means of distribution has been broken: they are giving their songs away free on the Internet knowing it will attract more people to their gigs.

Writers and filmmakers are following suit, offering entire works for download provided that the rules of Creative Commons are adhered to. Cory Doctorow, who describes himself as "a moderately successful sciencefiction author", put his first book, Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, on the Net in January 2003. Since then it has been downloaded by more than 300,000 people. More importantly, sales of the book far exceeded the initial print run an unusual feat for scifi books. Doctorow has since become an evangelist for Creative Commons. He argues that instead of being branded as pirates, people who download his material should be seen as readers who will pay him back indirectly: by spreading the word about his books and by developing his ideas further. While companies such as Fox Television (XFiles) and Warner Brothers (Harry Potter) have sued individuals who post on the Internet stories containing characters licensed by them, Doctorow takes delight in fan fiction where readers write alternative endings to his books.

This kind of writer/reader interaction is what people like Doctorow hope will result from the widespread use of Creative Commons. It is the opposite of the model of innovation expounded by large corporations, who see readers primarily as consumers rather than interactive participants.

Here lies the crux of the argument: does creativity depend on the ability to make profit, or does it thrive on the free exchange of ideas? When the Statute of Anne became the first codified copyright law almost 300 years ago authors wanted to make sure their books were not sold under another person's name. Today, copyright and the broader notion of intellectual property (IP) have become tradable commodities. Michael Jackson, for example, owns a large part of the Beatles' song lyrics; stock exchanges are preparing to start trading in patents; and America is pressing for harsh sanctions against "countries that fail to provide adequate and effective protection to US intellectual property".

As we enter the information age, intellectual property adds to the many intangible goods that already far outweigh the value of tangible goods traded around the world today. The prime beneficiaries of this regime are large corporations and IP lawyers.

According to Lawrence Lessig, Professor of Law at Stanford University, this is not the result of a concerted conspiracy by big business, but rather the outcome of "cultural blindness": a scramble for all ideas that could potentially be profitable is taking place that mirrors the period of land enclosures which saw Britain's common land divided into minute units and sold to large landowners.

Given that, as George Bernard Shaw wrote, imagination is the beginning of creation, the commodification of knowledge could result in a stranglehold on innovation. The development of cheap generic drugs, the principle of using credit cards to buy goods online, even the reproduction of historic public speeches such as Martin Luther King's 'I have a dream' have suffered the chilling effects of intellectual property law.

In his book Silent Theft, David Bollier warns that business is gaining ownership and control over resources that should belong to everyone, including natural resources, intellectual resources and essential public infrastructure such as the Internet and the electromagnetic broadcasting spectrum. All of these, he says, are part of the "common wealth" that needs to be protected from being sold off and becoming out of bounds to those who won't pay the entrance fee.

In 1982, Jack Valenti, head of the Motion Picture Association of America, told the US House of Representatives: "I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston Strangler is to the woman home alone." Two decades later it is not hard to see that he was wrong. The introduction of cheap, recordable video cassettes spawned new industries and gave a whole generation of wouldbe film makers the chance to hone their skills with Daddy's video camera.

The BBC Creative Archive, which takes its first steps this autumn with clips from the corporation's factual and documentary programmes, is an ambitious attempt at reclaiming the creative commons. Paul Gerhardt, joint director of the Creative Archive, says: "We want to work in partnership with other broadcasters and public sector organisations to create a public and legal domain of audio/visual material for the benefit of everyone in the UK. We hope the BBC Creative Archive can establish a model for others to follow, providing material for the new generation of digital creatives and stimulating the growth of the creative culture in the UK."

One person who has already taken this step is singersongwriter (and now Brazilian minister for culture) Gilberto Gil, who released his latest album under the Creative Commons banner giving others explicit permission to remix and reuse his work. His reasoning: "I'm doing it as an artist."