Since the launch of the first ever women's publication in Iran almost 100 years ago, Iranian women have not been mere observers of events or victims of social transformation; they've actively influenced political process through the emergence of women's newspapers, magazines and journals. Their struggle for full citizenship, documented and advanced through their own media, is all the more remarkable in the context of the continuing oppression of women in Iran.

And the vexed question of the position of women is revived whenever there is a change of regime. The first act of the Islamic Republic under the leadership of Khomeini, for example, after the deposition of the monarchy in 1979, was to impose 'reveiling'. If the forced 'deveiling' under Reza Shah in 1936 was celebrated as a major sign of progress, the forced 'reveiling' came to signify the triumph of 'tradition' over 'modernity' and a major step towards recovering the Islamic roots of Iran.

In the first few years of the Islamic Republic many of the rights that women had gained under the Pahlavis were taken back. The segregation of the sexes in public spaces; overt sexual discrimination; compulsory hijab; the exclusion of women from a number of professions and their redirection to work mainly as teachers in girls' schools, nurses and secretaries; their disbarment from serving as judges; the reinforcement of patriarchal policies in matters of divorce and guardianship of children; and lowering the age of marriage for girls were among measures used to 'purify' women and society and bring back the 'glorious' tradition of what was perceived to be the true Islam.

At the same time, although Khomeini had always been opposed to women's rights to vote, once he returned to Iran he came to recognise the usefulness of their political support. Therefore, women's inclusion in demonstrations, their active support in times of war, their mobilisation as the guardians of morality, and their votes in elections were regularly used by the regime to achieve its goals and crush the secular, middleclass women's movement in Iran.

Whatever the motives, this policy paved the way for the participation of a large number of women in politics, which raised their awareness to the point where it was hard for the regime to persuade them to go back to their traditional roles and lives.

Women's publications both documented and influenced campaigns which have successfully brought about changes in education, family planning, divorce law and the return of women judges to the courts, if only in advisory capacities. Under pressure, in 1988 the state established the Social and Cultural Council of Women to encourage further participation of women in social and economic spheres. The Council of Women soon began to produce its own quarterly publication Faslnameh. The Office of Women's Affairs, part of the newlook presidential office, was created. After the landslide victory of Khatami and the more liberal clergy in 1997, many ministries took on women advisers, many of whom had been prominent in journalism. So the women's press played an important role in forcing gender to the top of the agenda.

The concept of ijtihad (independent reasoning or/and interpretation) has been used effectively by reformists in Iran to push forward arguments for modern readings and interpretation of Islamic principles and texts, and has strongly influenced debates about feminism.

In the past decade a number of women's publications have emerged that seek to offer modern interpretations of Islamic law to enshrine women's rights. These publications, mostly run and edited by women, have been an important part of a vibrant and critical press which emerged in the 1990s and helped the cause of the reform movement. The most influential was the monthly Zanan (Women), established in 1992 as a platform for discussing questions of gender equality in Islam, family and civil law, political participation, employment and individual freedom.

It soon made a name for itself by entertaining the possibility of alternative readings of the Koran and Sharia in the modern context, as well as by opening its pages to secular writers who had no other platform.

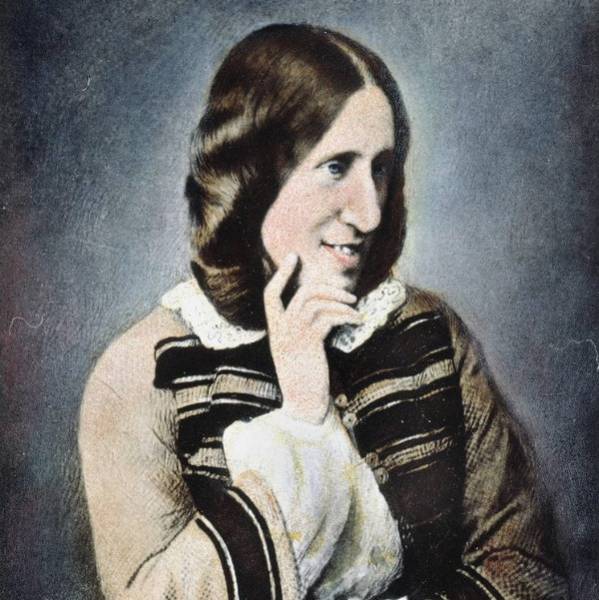

The first ever daily paper devoted to women, Zan (Woman) was launched in August 1998 by Faezeh Hashemi, daughter of the previous president Rafsanjani and a member of parliament in her own right. From early on Zan attracted the wrath of the conservative faction and after facing a number of charges, penalties and temporary closure, it was finally ordered to cease publication in April 1999, mainly for publishing a satirical cartoo(shown above) criticising the Ghesas (retribution) law which asserts that the blood money for a murdered woman is only half of that for a man. The cartoon showed a gunman pointing at a couple, with the husband shouting "Kill her, she is cheaper!"

Since 2000 the conservative backlash against the reformist press has resulted in the banning of more than 80 publications. However, the closures have not managed to curtail a defiant women's movement that has been one of the most visible oppositional movements in Iran. The Islamic Republic has not heard the last from a generation of women activists, both secular and Muslim, who still continue to press for their rights.