Say 'artificial fertilisation' in predominantly Roman Catholic Italy and you will immediately enter a debate where moral censors, ardent feminists, patronising priests, politicans and doctors promising medical miracles face each other in a conflict that has already produced one big loser: a public seeking balanced information on a new IVF law passed by the Italian parliament last year. And as the country braces itself for a mid'June referendum on the issue aimed at overturning the law, Italy risks being locked in an ideological battle that overshadows a proper debate on the moral limits and possibilities of science.

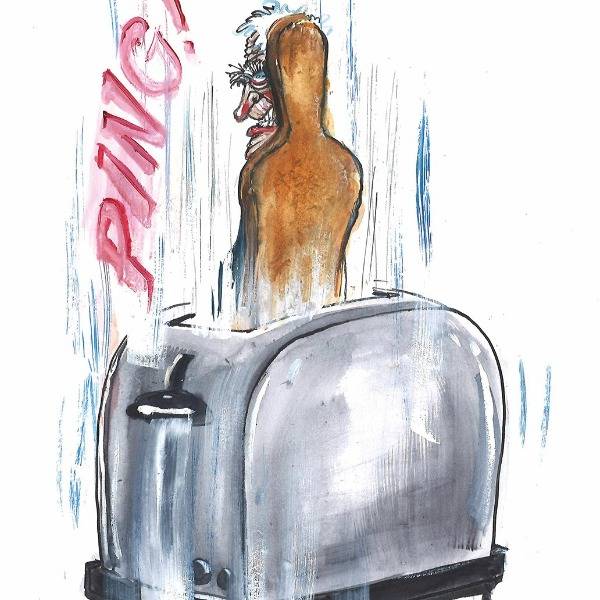

'The more it gets clouded by an increasing array of opposing opinions voiced in a ping pong of televised debates, the less the discussion on artificial insemination helps those who want to understand it,' wrote former Italian prime minister Giuliano Amato in Italy's Corriere della Sera recently. 'It really seems as if we are going backwards, to pre'Galileo times.'

Italy's Medically Assisted Reproduction Law caps fertility treatments by severely limiting the scope of assisted fertilisation techniques: it prohibits the use of external donors; it effectively gives embryos the same rights as human beings; and it bars the screening and freezing of pre'implanted embryos and any embryo research.

Under the law, doctors may take no more than the first three eggs resulting from ovarian stimulation, and have to implant all resulting embryos. If the pregnancy fails and the woman wishes to try again, she has to repeat the whole painful and psychologically'draining procedure.

Critics say these rules put the health of mothers and potential children at risk, while backers say pre'implanted embryos are human beings and must therefore be legally protected as such. Some even go as far as suggesting that the genetic screening of embryos would breach the privacy rights of the embryo.

Ironically, many of the supposed champions of morality have no qualms about urging voters to boycott the ballot. 'In the name of the embryo' everything is allowed.

Powerful Roman Catholic cardinal Camillo Ruini, head of the Italian Bishops' Conference, recently called on citizens not to vote at the referendum in the hope it won't reach the quorum of 50 per cent plus one it needs to be valid. 'We are not saying, 'do not vote in elections'. We only think it would be useful not to vote in this referendum,' he told newspaper La Repubblica.

The constitution says that if a referendum does not reach the quorum, the result is void, meaning the new IVF law would remain in place.

Backers of the referendum warned that Ruini and his flock were undemocratically stepping into state affairs and seeking to limit the freedom of scientific research. 'We are not suggesting going backwards in history. By affirming the importance, even in the public sphere, of Christianity, (') we are not renouncing the distinction between Church and State,' replied Ruini.

His comments unleashed a wave of praise from across the Catholic bloc that spans the entire political spectrum, and politicians were quick to to take the opportunity to jump to his defence in the emotionally'charged days that followed the death of Pope John Paul II.

But one of the harshest criticisms of the ballot boycott came from the most unexpected source.

In what has become known as 'Veronica's outing', the wife of centre-right prime minister Silvio Berlusconi spoke out against the abstentionists, embarrassing her husband, whose coalition drafted and passed the controversial law.

'To abstain from voting means not dealing with the problem. Voting forces people to inform themselves about the issue and to take a decision according to their religious, philosophical or political convictions. It is important not to pretend that the problem doesn't exist,' Veronica Berlusconi told Corriere della Sera.

Figures show that the number of couples seeking artificial insemination abroad has increased, while the number of successful pregnancies has dropped. Couples who have more money are at an advantage over those who are poorer because they can simply get on a plane to a country with laxer fertilisation laws. Promoters of the referendum cite this trend as a major reason for overturning the law.

As emotions run higher, little has yet been said about another important side to this debate: the relationship between women and medicine, between body and science. Few voices have raised this issue at all, and even fewer seem to remember that women have battled for decades against a kind of science that sought to control their bodies or experiment with them.

While some might argue it is a scientifically flawed comparison, it must be pointed out that that the people who champion the genetic screening of embryos are often the same who speak out against genetically-modified crops. Clearly the issue of the genetic screening of embryos has not been thought out in all its facets.

'I would like to see an authoritative caution among the centre-left on technologies which concern the body of women and the power to generate human beings. I would like to see a bit of healthy diffidence towards scientists who build a business around the desire to become mothers,' said AlessandraDi Pietro, a feminist journalist who used to be spokeswoman of leftist former Equal Opportunities Minister Katia Bellillo.

At the core of the question, as Di Pietro herself points out on the pages of Il Foglio newspaper, is the fact that 'the attitude of those who buy into, and therefore finance, the market of biotechnologies, can have a much bigger impact on the direction that scientific research will take than mere prohibitionism.'

That's why, rather than erecting ethical barricades, it would be wise, and morally and politically responsible (not to mention far-sighted) on the part of both backers and opponents of the law, to help citizen understand the issue and make a responsible choice in the referendum rather than pressure them on ideological grounds or bombard them with dogmas. In the end, Italians will have to live with the consequences.

Raffaella Malaguti is a freelance journalist based in Rome.