In the movie Crash, a young white male police officer with a firm commitment to equal treatment for everyone, ends up shooting a black hitchhiker. Why? He thought the hitcher had been pulling a gun on him, when, in reality, he'd been trying to evince some fellow feeling by showing that he had a similar figurine patron saint of travellers to that which sat on the officer's dashboard. It's a moment that shows how readily our preconceptions and prejudices and half-knowledge about others can have calamitous consequences. It's a moment that demonstrates the contemporary sensitivities and complexities of handling race relations.

How might such cognitive and emotional presuppositions be remedied? The obvious people to turn to for answers are the self-proclaimed race experts: the thousands and thousands of diversity trainers and multicultural counsellors and race education professionals who can claim special knowledge and special awareness about such matters.

But any examination of the ministrations and advice which these gurus offer in their high priced diversity training videos, sensitivity manuals, and ethnicity workshops, show that rather than resolving current issues and problems about race, they are actively compounding them.

There have been several excellent satirical attempts to show the sort of craziness that can ensue when one ethnic group attempts 'sensitive interaction' with another. In the late 1960s Tom Wolfe perfectly captured the inanity of a fund-raising dinner given by members of the New York white Liberal elite for the Black Panthers. Host, Leonard Bernstein, relished the Panthers' self-assertion, trembling with vicarious excitement as his guests of honour displayed the black power symbol the upheld fist. Neither was Wolfe alone in chronically post-civil rights antics and ironies.

In the famous 'show me the money' scene from the movie Jerry Maguire, the character played by Cuba Gooding, Jr, a star black football player, has his agent, played by Tom Cruise, grovelling desperately in order to keep him as his client. Cruise's character capitulates to the player's every demand in an amusing verbal volley as he is forced to demonstrate at ever higher decibels his utter devotion. In his book, The Content of our Character, Shelby Steele called this the 'harangue-flagellation ritual', and confessed that at a less mature age he had even resorted at times to the cocktail-party pleasure of playing the race card in order to provoke liberal guilt.

There is also a long history of playing 'the race card'. Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright both unmasked radicals and fellow travellers who used the plight of blacks to their own political or psychological ends and demonstrated, in The Invisible Man and Native Son respectively, how fatal such bad faith could be for the very individuals radicals championed.

But these relatively rarefied instances of the manner in which interracial etiquette can result in bad faith have now gone mainstream. In the mid 60s, as the civil rights movement lost it's direction, universalistic claims for full civic inclusion were replaced by militant assertions of the significance of identity.

That early movement was stunningly successful, mounting an assault on de facto and de jure segregation, countering white supremacy, and exposing the racial crimes of the nation's past. But the new militancy of the late 1960s an emphasis Martin Luther King, Jr, understood but rejected coupled with a larger shift in the culture toward a therapeutic ethos, ushered in a way of talking and thinking about race that departed drastically from the earlier movement.

It was this newer set of ideas about race, which cast race as a fundamental aspect of individual identity and individual identity as something to embrace and assert, that inspired many of those in the late 20th century diversity industry. While the brilliance of civil rights universalism was precisely its attack on racialised ways of viewing and treating individuals, the cult of identity reinvoked differences as inexorable, positive, and a rightful determinant of political opinion. Satire and fiction might leave us laughing and ready to move beyond this phase, but new cultural forms interracial etiquette, new age therapy, sensitivity training have given differential thinking a new lease on life.

One of the most famous diversity training materials is a film called Blue Eyed. Used frequently in schools, workplaces, and other venues, it depicts a diversity training technique invented and put into action by schoolteacher turned diversity-trainer Jane Elliott, first with her elementary school pupils in 1968 and since then in numerous other settings. The film depicts one of her diversity training workshops in action. Her approach is to divide people into two groups by eye colour, with the brown-eyed labeled as privileged, attractive, and superior, and the blue-eyed as oppressed, unattractive, and inferior. Meeting separately with the brown-eyed group, she prepares it to act in the most demeaning fashion possible toward the blue-eyed participants. The blue-eyed members rejoin the workshop, only to be assaulted verbally with every racial slur imaginable and treated with rude interruption, bullying, and the like. Elliott contradicts herself, changes rules in midstream, and otherwise acts in an imperious fashion, delivering random insults and invective all vaguely aimed at the supposedly constructive end of emotional release (as in the Esalen encounter groups, which pioneered racial confrontation therapy).

In the classroom setting in Riceville, Iowa, one can only imagine the effects of the original experiment on the unsuspecting children. In her videos, Elliott offers an interpretation of the outrage of the local parents as further indication of their backwardness and racism. When adult members of the diversity training workshops react with tears or protestation, Elliott takes the opportunity to humiliate them with accusations that their privilege has protected them until now from the hurt of oppression.

Not all diversity training materials are as blatantly inspired by the 'aggressive black, guilty white' model of interracial interaction, yet many that on their surface seem more benign still bear the mark of the obsession with identity and difference. Because they lack clarity about overriding principles or a single standard of civility and respect, the very things civil rights pioneers risked their lives for, they often end up erecting a complicated set of guidelines for interactions among people of different groups.

Diversity materials and multicultural etiquette advice manuals commonly direct their messages at managers who have to deal with a diverse workforce or business people who need to clinch deals with people from another country. Attempting to distill guidelines into the simple bulleted outline omnipresent in the management literature, etiquette gurus advance just the sort of simplistic generalisations about whole groups of people the civil rights movement sought to combat. One of them suggests that the best approach, for instance, is to note that members of different groups have different views of such things as punctuality and respect for authority, and goes so far as spelling out which groups believe what. This is not just a recipe for disaster and new tensions in the workplace, but also a licence to perpetuate stereotypes now in the supposedly legitimate form of antiracism.

In the hands of many diversity experts in corporations, government, universities, aond beyond, our differences expand in importance, eclipsing our commonalities. Differences are cast as something inexorable, unchanging, and unbridgeable.

At its worst, current thinking about race, codified in identity politics, stands in for a public philosophy, since it claims to offer understanding of our common life that answers the underlying question of not just how we get along but why we do. Today a coherent sense of commitment to the common good with its definition of citizenship as entailing responsibilities as well as rights and privileges is in short supply. It is crucial, in this void, to challenge this cult of difference and find more meaningful strategies for self-definition.

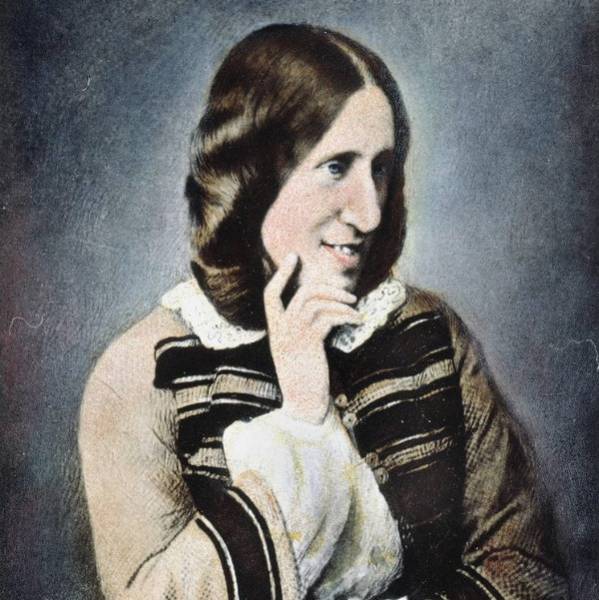

Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn is Professor of history at the Maxwell School, Syracuse University