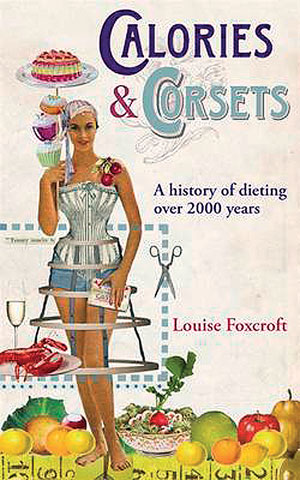

You may think you’re just trying to lose a bit of weight, and you may need to. After all, as many as one third of all men and women in the Western world are thought to be overweight, while a recent European Commission survey of 19 countries showed that women in the UK are the heaviest of all. But although obesity is reaching pandemic proportions, the obsession with diets and slimming is far from new.

As Louise Foxcroft tells us in Calories & Corsets, her entertaining new history of slimming, diets have been around since ancient times. And they have always been about much more than food. They are a guide not merely to healthy eating but to morality. Even for the ancients, food and diet were intricately linked to ethical philosophy. Moderation was the key. Excess and greed would lead to dissolution and disease, while the good life required restraint and discipline.

And this idea was seized upon with almost obscene enthusiasm by the early Christians. At the end of the third century early ascetics like Saint Antony went off to live solitary lives in the desert, where they adhered to a punishing regime of near-starvation in order to overcome the devilish demands of the body.

“Using prayer to banish fat has a long history,” argues Foxcroft, “from St Augustine of Hippo in the third century AD to Deborah Pierce in 1960, author of I Prayed Myself Slim.” Hermits, priests, philosophers across cultures have adopted asceticism as a route to goodness and godliness, while fatness was deemed a visible manifestation of greed and indulgence. No wonder gluttony found its place so quickly among those seven deadly sins.

But just as important as abstinence is the establishment of strict rules for what is acceptable to eat. The Book of Leviticus lays down in minuscule detail what is allowable, dividing prawns from plaice, milk from meat, and laying strange emphasis on cud-chewing and cloven hooves. Jews and Muslims recoil from eating pig, Hindus from cows.

It’s a cognitive phenomenon studied by the anthropologist Mary Douglas. She argues that societies and cultures need these elaborate codes of practice. They are a form of social control but also of social protection. And food is an ideal vehicle for prescribing what is clean and what should be banned. But even then the choice of taboo is arbitrary. The fact of it is what matters.

So when we diet, we’re not simply attempting to lose weight. We’re following the age-old cycle of denial and excess where whatever is deemed sinful takes ascendance and becomes more covetable. Every modern slimming diet will formulate its own set of rules into a metatext of forbidding. Nothing but grapefruit and the occasional piece of toast. Only raw fruit for three days. The California diet? As much fruit as you like but nothing else. The hip and thigh diet? Fibre and whole foods but no sugar, no fat, no alcohol.

What is striking about Lousie Foxcroft’s catalogue of diets through the centuries is the consistency of the advice; while they have been dressed up in different guises to suit the inclinations of the time, even the earliest regimes bear a striking similarity to today’s. All are characterised by this relentless insistence on set and unwavering regulations on what can and cannot be eaten. As long ago as 1558 a Venetian merchant named Luigi Cornaro, in his diet book The Art of Living Long, was recommending a strategy very much like the WeightWatchers calorie-counting model.

And if you thought the Atkins diet was revolutionary, meet Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who, in 1825, published a diet book, The Physiology of Taste or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy. This advocated abstinence from all farinaceous food as well as starches and sugars. In other words, it was a classic no-carbs diet – echoed later by that of William Banting which, first published in 1863, became so popular that right until the 1920s the word “banting” was synonymous with “dieting”.

One 19th-century diet guru, Dr AW Moore, devised the now commonplace idea of a Diet Diary, laid out in columns and sections so that you could fill in what you ate each day and then record your weight. Meanwhile the Presbyterian minister Sylvester Graham, inventor of the Graham Cracker, railed against a bizarre range of foodstuffs including meat, sauces, alcohol, pepper and mustard, and also advised washing in tepid water each morning, drying oneself roughly until red as a boiled lobster and finishing with half an hour of brisk walking.

The more precise the rules, the more people believe they will work. The Hays diet fussily advises on how to combine and separate various food groups. Atkins disciples don’t just cut down on pasta and bread. Not a crumb of it must touch your lips or your metabolism will revert, the magic will tarnish. The formula relies on an atavistic belief that something deeper than mere food consumption is at work: something that moves in mysterious ways. The slimming world has co-opted the language of faith, the exhortation of the pulpit. Its tactics are identical: to prey on the guilty and insecure, then offer salvation through faith and goodness. Most diets promise miracles. “Get a Flat Tum in Five Minutes a Day!” “Lose a stone in just six weeks!” To achieve this state of grace you must follow the true path and never stray, though sin can be forgiven.

The multimillion industry of WeightWatchers relies heavily on the culture of confession. In church halls up and down the land members make their weekly confessions with the ritual humiliation of the scales, then receive the blessing and forgiveness and the chance to start again.

While the road to salvation may be familiar, its ultimate destination these days has shifted: from the next world to this one, from a spiritual heaven to a personal one. Self-affirmation is the mantra of the saints of the slimming world, the diet divas. “Losing 12st 1lb has given me the gift of life,” caroled one of Rosemary Conley’s Slimmers of the Year. And the Atkins message is the same. “This book will show you how to change your life once and for all.” Purity of the soul has been converted to purity of the body through the grace of detox.

The drawback is that it’s so very dull. Moderation may be the mantra of rationalism, but it doesn’t leave much room for that other vital human quality: pleasure. Indeed, it could be our obsession with thinness itself that’s irrational. So why not forget about your yearning for a Size Zero shape or an impossibly flat stomach? Learn to love yourself just as you are.

So I’d like to propose a toast to unfettered, abandoned appetite. Humanists everywhere should be able to break bread together without worrying too much about its carb level or its calorie quotient. Invite strangers into your home, insist on gorging and gluttony, let your table groan with excess. Reach out to the camaraderie and lusts of everyone who has rejected the bloodless rules of the godly and the smug.

Let’s have a feast day to celebrate reason. Let’s indulge in our greed, give thanks for our original sins and join together to say no to easy answers and yes to life with all its cruelties, dangers and fabulous guilt-free food.

The author is seven and a half pounds overweight