In 2002, the Pompidou Centre in Paris held the massive “Surrealist Revolution” show and the Tate Modern hosted, and then exported to New York, the equally huge “Surrealism: Desire Unbound”. Last year, the Barcelona Centre of Contemporary Culture put on the blockbusting “Paris and the Surrealists” and earlier this year the Hayward Gallery successfully carried off “Undercover Surrealism”. As I write, the Whitechapel Art Gallery continues to busy itself presenting the critically regarded “Vicious Circle” exhibition, devoted to the closely related surrealist milieu of the painter Hans Belmer and the philosopher Pierre Klossowski. And now here we have this paperback collection of essays on the subject of surrealism by one of its original adherents.

Are we in the midst of a surrealist renaissance? After all, apart from the numerous gallery explorations of the phenomenon, we are also confronted by dramatic examples of what might be called surrealist tropes in the contemporary global videodrome. I am not just referring to the stagy plasticine weirdness of contemporary junk culture, but to something darker and more sinister. Is there not something quintessentially surreal about a world which is dominated by the ever-escalating consequences of a suicide mission that involved flying planes into the highest skyscrapers in New York? Remember the infamous definition of the simplest surrealist act issued by André Breton in the Second Manifesto: “Descending to the street with revolver in hand and shooting at random, as fast as one can, into the crowd.”

Are we in the midst of a surrealist renaissance? After all, apart from the numerous gallery explorations of the phenomenon, we are also confronted by dramatic examples of what might be called surrealist tropes in the contemporary global videodrome. I am not just referring to the stagy plasticine weirdness of contemporary junk culture, but to something darker and more sinister. Is there not something quintessentially surreal about a world which is dominated by the ever-escalating consequences of a suicide mission that involved flying planes into the highest skyscrapers in New York? Remember the infamous definition of the simplest surrealist act issued by André Breton in the Second Manifesto: “Descending to the street with revolver in hand and shooting at random, as fast as one can, into the crowd.”

But how can an historical movement that explicitly regarded itself as revolutionary, utopian and avant-garde truly be said to be undergoing a revival, theoretical or otherwise, when the forces sponsoring this revival mostly consist of the most rarefied upper echelons of the cultural establishment? This is one of the questions directly addressed in this volume, a diffuse medley of essays, reviews, polemics and panegyrics on various surrealist figures and themes, penned between 1929 and 1953 by the dissident French thinker.

It was a fascinating period, and Bataille was himself a singularly fascinating man – a close but strained surrealist associate whose many other activities and interests included philosophy, sociology, mysticism, eroticism, anti-fascism, poetry, human sacrifice (both theoretical and practical) and librarianship. What this book charts is his changing understanding of and stance towards surrealism, from an initial period of lunatic resentment (“The Castrated Lion”) to an eventual critical, admiration for it. This transformation is biographically interesting, and two of the texts in this volume (“Notes on the publication of “Un Cadavre”” and “Surrealism from Day to Day”) find Bataille writing with searing sincerity about his own youthful missteps and errors of judgement, while at the same time providing a crystalline series of thumbnail sketches of the leading members of the literary surrealist circle (Breton, Louis Aragon, Antonin Artaud, Michel Leiris, etc) .

What lies at the very heart of this volume, though, is Bataille’s insistence, specifically asserted in his essay “Surrealism and How It Differs from Existentialism”, that surrealism “surpassed the artistic and literary domain.” Surrealism was not just a hobby or a movement or a genre but a matter of life and death.

This claim pitched Bataille against all comers in the endless series of contretemps which characterise French intellectual life. In particular it meant a confrontation in postwar Paris between him and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who were busy burying Breton and his movement alive. In the words of de Beauvoir, surrealism evinced “a preoccupation with the unconscious and not the totality of man” – an elision which caused it to fall prey to the classic pseudo-radical bourgeois trap of serving as a mere mystical affectation of action, rather than action itself.

Bataille bristled at these accusations and drew a diagonal across them. His own view was that surrealism was an entirely new kind of phenomenon – an ambivalent mysticism based on the absence of myth, a paradoxical poetry built on the absence of poetry, a meaningless practice concerned with imbuing “even the smallest action with a meaning that involves the fate of mankind”.

It is this type of assertion by Bataille which effectively undermines the notion that the current cultural celebrations of ‘surrealism’ (as well as our conversational readiness to attach the label ‘surreal’ to events that merely strike us as strange, anachronistic, or inane) can in any way constitute a revival of surrealism.

What such usages of the term suggest, and what this volume makes so abundantly clear, is that we have forgotten how shocking, radical, subversive and incapable of easy appropriation surrealism once was. ■

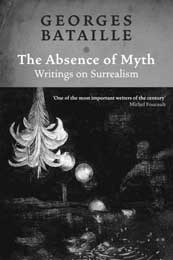

The Absence of Myth is published by Verso