David Harvey was quickly into his stride. “Capitalism,” he told his lunchtime audience at the Royal Society of Arts in London, “never solves its crises. It simply moves them from one place to another. From Brazil to Russia to Argentina to America to Britain to Greece.”

David Harvey was quickly into his stride. “Capitalism,” he told his lunchtime audience at the Royal Society of Arts in London, “never solves its crises. It simply moves them from one place to another. From Brazil to Russia to Argentina to America to Britain to Greece.”

As he began to analyse the reasons for these recurrent crises, and in particular for the way in which their frequency had dramatically increased since the 1970s, I allowed myself a look at the audience. From my chairman’s seat I could see that the lecture theatre was packed. Every seat was taken and there were a dozen or so latecomers standing in the aisles. The RSA lunchtime lectures are usually well attended, but did everyone in the room on this occasion recognise that what they were about to hear from today’s speaker was an analysis of contemporary capitalism that began and ended with Marx, an analysis that in many respects was identical to the one I’d heard developed before tiny audiences of hard-line socialists in a hundred unprepossessing venues during the ’70s and ’80s?

I need not have worried. For even though Harvey quickly acknowledged his debt to Marx and freely quoted from his work, there was no sign of restlessness in his well-heeled audience at any point during his 30-minute address and only one speaker in the Q & A session that followed even ventured to suggest that anything other than a Marxist analysis might be best suited to understanding our current economic plight.

There was, of course, a very good reason for this readiness to accept an economic doctrine that appeared, however unreasonably, to have been consigned to history by the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was, quite simply, the evident failure of the world’s economists to produce any other satisfactory account of the events of recent history. Harvey has a neat way of bringing this fact home to his audiences.

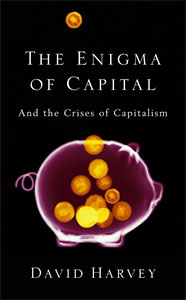

In the preamble to his latest book, The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism, he tells this story: “When Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II asked the economists at the London School of Economics in November 2008 how come they had not seen the current crisis coming (a question which was surely on everyone’s lips but which only a feudal monarch could so simply pose and expect some answer), the economists had no ready response. Assembled together under of aegis of the British Academy, they could only confess in a collective letter to Her Majesty, after six months of study, rumination and deep consultation with key policy makers, that they had somehow lost sight of what they called ‘systemic risks’.”

Harvey thoroughly relishes the almost Swiftian irony of this episode: the spectacle of learned economists desperately trying to excuse their own failure while terribly aware that not one of them is wearing any clothes. But it also provides him with the perfect way to invoke Marx. Those bewildered economists had finally, after those six long months, recognised the true nature of their failure. Forget all the other half-cock theories proposed by journalists and commentators. The latest crisis, Harvey tells his rapt RSA audience, wasn’t precipitated by human frailty or by inadequate financial regulation or by forgetting Keynesian insights or by the distinctive cultural failings of the English or the Americans or the Greeks. It was a systemic failure of capitalism. And the only plausible account of that type of failure is to be found in good old Marx.

Harvey thoroughly relishes the almost Swiftian irony of this episode: the spectacle of learned economists desperately trying to excuse their own failure while terribly aware that not one of them is wearing any clothes. But it also provides him with the perfect way to invoke Marx. Those bewildered economists had finally, after those six long months, recognised the true nature of their failure. Forget all the other half-cock theories proposed by journalists and commentators. The latest crisis, Harvey tells his rapt RSA audience, wasn’t precipitated by human frailty or by inadequate financial regulation or by forgetting Keynesian insights or by the distinctive cultural failings of the English or the Americans or the Greeks. It was a systemic failure of capitalism. And the only plausible account of that type of failure is to be found in good old Marx.

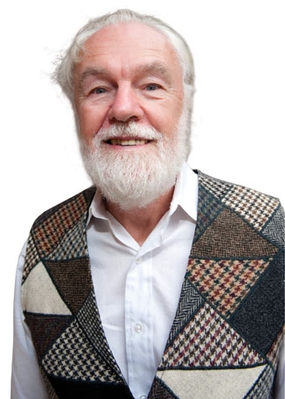

There are other reasons why Harvey commands so much attention. With his carefully trimmed beard and slightly avuncular appearance he looks like a very gentle revolutionary. He is also very eloquent. His books and lectures on the contemporary relevance of Marxism – his internet lectures on Capital have been downloaded by more than a quarter of a million eager students – have the sort of literary verve and sense of assurance that recall Marx at his very best. He is particularly compelling when depicting capitalism as an endless flow that is constantly overcoming barriers as it seeks new opportunities for profit. It’s a metaphor that he happily attributes to his early-17th-century namesake William Harvey, the first person to show systematically how blood circulated through the human body. Here is that metaphor being put to work:

“On the one hand the international institutions and peddlers of credit continue to suck, leech-like, as much of the lifeblood as they can out of all the people of the world – no matter how impoverished – through so-called ‘structural adjustment’ programmes and all manner of other stratagems (such as suddenly doubling fees on our credit cards). On the other the central bankers are flooding their economies and inflating the global body politic with excess liquidity in the hope that such emergency transfusions will cure a malady that calls for more radical diagnosis and interventions.”

Like all good Marxists, Harvey revels in such contradictions and paradoxes. As he told me when I interviewed him after his talk, “I’m a dialectician. I believe in mining the contradictions that exist in a society and trying to use them in the course of progressive change. It’s a mode of thinking and explanation which is very easy to work with if you use it in such a way that people can relate to, rather than saying you have to read three volumes of Hegel or four volumes of Marx in order to be able to understand it. The structure of a good play like Hamlet has a dialectical structure. If it didn’t have one it would be very boring. And I find history and historical change fascinating for exactly the same reasons.”

In his RSA talk and in his very readable new book, Harvey particularly relishes the contradictions that arose from the neoliberal revolution of the Thatcherism years. Back then the problem for capitalism was defined as the power of labour in relation to capital. Profits could only be ensured if organised labour was forced into retreat by new anti-union legislation and by the development of global out-sourcing, which allowed employers to make use of docile labour forces in the under-developed world. But this immediately created a new problem. Now that real wages had been effectively depressed, how might the workers afford to buy the goods that capitalism was producing? The answer was to be found in easy credit.

Much of this credit was used to fuel the housing market. But here lay another contradiction. On the one hand the banks handed out long credit lines to the developers so that they could build more houses. But then the same financial institutions offered credit to those who wished to buy the newly erected property. It was, said Harvey, a perfect example of a Ponzi scheme, an investment fraud that involves the payment of purported returns to existing investors from funds contributed by new investors. And like every other Ponzi scheme, the whole edifice collapses when investors decide to cash out.

But how can we explain the readiness of so many people to invest in an area that seems so relatively precarious compared, for example, to an investment in manufacturing? And this is where we come to the core of Harvey’s analysis. The proliferation of financial crises in recent years, he argues, has been driven by capitalism’s commitment to producing a compound annual growth of three per cent. In the past, in a limited world with so many unexploited markets, this was a realisable target for countries like the UK and the States. But now that China and India are also growing at a similar or even faster rate, there is a massive shortage of places where the surplus profits from capitalist enterprise can be invested. At present a surplus of £1.5 trillion is in search of new investment opportunities. In 20 years’ time that figure will rise to £3 trillion. Hence the invention of what Harvey likes to call “fictitious markets”: the markets in derivatives, derivatives of derivatives, in futures, and in carbon trading. Initially these offer better returns than investments in industry but they are, as we have all seen to our cost, eventually illusory.

As the close attention of the RSA audience made clear, it is difficult not to be impressed by this argument, particularly when it is contrasted with the bit-and-piece explanations that have been proffered by other economic commentators over the last 12 months. But I can’t contain a certain feeling of uneasiness as we reach the point in the talk where Harvey is going to have to propose a radical solution to the present situation, where he seems likely to suggest that this latest crisis is the final nail in the coffin of capitalism. I’m wary because there have been so many similar predictions in the past. Capitalism, we’ve been variously told by Marxist theorists, reached its apotheosis with the 1973 oil crisis or the IMF crisis in 1976 or with Black Monday in 1987 or Black Wednesday in 1992. But the prophecies all failed. Again and again, capitalism proved itself capable of survival, of regeneration. So is there really anything about the present situation that is truly different?

I need not have worried. Harvey is only too ready to acknowledge the capacity of capitalism to find new ways of surmounting crises and returning to successful profit making. In the past it has found many “irrational” ways to achieve this end. It has done so, as he puts it in The Enigma of Capital, by “destruction of preceding eras by way of war, the devaluation of assets, the degradation of productive capacity, abandonment and other forms of ‘creative destruction’”. All of these solutions have produced alarming consequences. “Human lives are disrupted and even physically destroyed, whole careers and lifetime achievements are put in jeopardy, deeply held beliefs are challenged, psyches are wounded and respect for human dignity is cast aside. Creative destruction is visited upon the good, the beautiful, the bad and ugly alike. Crises, we may conclude, are the irrational rationalisers of an irrational system.”

I need not have worried. Harvey is only too ready to acknowledge the capacity of capitalism to find new ways of surmounting crises and returning to successful profit making. In the past it has found many “irrational” ways to achieve this end. It has done so, as he puts it in The Enigma of Capital, by “destruction of preceding eras by way of war, the devaluation of assets, the degradation of productive capacity, abandonment and other forms of ‘creative destruction’”. All of these solutions have produced alarming consequences. “Human lives are disrupted and even physically destroyed, whole careers and lifetime achievements are put in jeopardy, deeply held beliefs are challenged, psyches are wounded and respect for human dignity is cast aside. Creative destruction is visited upon the good, the beautiful, the bad and ugly alike. Crises, we may conclude, are the irrational rationalisers of an irrational system.”

But although he is eager to show that the present crisis is more critical than many of those that have been overcome in the past, and equally eager to suggest that any sensible person would now have no option but to join an anti-capitalist organisation, he is far from apocalyptic.

“Can capitalism survive the present trauma? Yes, of course.” But, Harvey explains, it can only do so at a terrible price. The mass of the people will be required “to give generously of their fruits of labour to those in power, to surrender many of their rights and their hard-won asset values (in everything from housing to pension rights) and to suffer environmental degradations galore, to say nothing of serial reductions in their living standards which will mean starvation for many of those already struggling to survive at rock bottom. More than a little political repression, police violence and militarised state control will be required to stifle the ensuing unrest.” (Even as Harvey spoke the battles on the streets of Athens were beginning to escalate.)

This was not, however, a reason for pessimism. “Crises are moments of paradox and possibility out of which all manner of alternatives, including socialist and anti-capitalist ones, can spring.”

I was anxious to know more about these alternatives. Wasn’t there a paradox at the heart of even his modest belief that alternatives to capitalism might arise from the present crisis? After all, one of the consequences of neo-liberalism had been the virtual destruction of the power of organised labour as well as the spread of an individualism that surely militated against the growth of any new forms of collective action.

Harvey is happy to agree that the possibility of any anti-capitalism movement depends upon a fundamental shift in mental conceptions. And it is unlikely that any lead in this respect is going to come from the academy. “Universities continue to promote the same useless courses on neo-classical economic or rational choice political theory as if nothing had happened and the vaunted business schools simply add a course or two on business ethics or how to make money out of other people’s bankruptcies. After all, the crisis arose out of human greed and there is nothing that can be done about that!”

Neither can we hope for any sudden rise in revolutionary consciousness among the traditional Marxist proletariat. In the past these industrial workers were always seen as the vanguard of the revolution. But this, suggests Harvey, was a mistake. “This fixation on factory labour as the locus of ‘true’ class-consciousness has always been too limited, if not misguided (leftists have erroneous ideas too!). Those working in the forests and the fields, in the ‘informal sectors’ of casual labour in the backstreet sweatshops, in the domestic services or in the service sector more generally, and the vast army of labourers employed in the production of space and of built environments or in the trenches (often literally) of urbanisation cannot be treated as secondary actors.”

These workers, who have been sometimes grouped under the term “the precariat” as a way of emphasising the unstable nature of their lives and their employment, have grown in numbers over the last 30 years precisely because of the changed labour relations imposed by neo-liberalism.

And Harvey cites another grand category of the dispossessed. This includes “all those peasant and indigenous populations expelled from their land, deprived of access to their natural resources and ways of life by illegal and legal (that is, state-sanctioned), colonial, neo-colonial or imperialist means, and forcibly integrated into market exchange … by forced monetisation and taxation.”

Although Harvey is happy to talk of the “dream” of a grand alliance between the deprived and the dispossessed of the world, he recognises that many of the movements that might be formed from such groups are liable to be local, inchoate and even counter-productive. But “to the degree that many of them exist in the same space, such as within the metropolis, they can (as supposedly happened with the factory workers in the early stages of the industrial revolution) make common cause and begin to forge, on the basis of their own experience, a consciousness of how capitalism works and what it is that might be done collectively.”

There are other groups that might join the common cause against capitalism: the social movements that have arisen to resist displacement and dispossession in such places as Brazil and India, and the emancipation movements around questions of identity in which women, children, gays and racial, ethnic and religious minorities have demanded “an equal place in the sun”.

It would be a mistake, though, Harvey maintains, to use the word “communist” as a label for all those who wish in their various ways to escape the limits and failures of the capitalist system. “Communism is, unfortunately, such a loaded term as to be hard to re-introduce into political discourse. Perhaps we should just define the movement, our movement, as anti-capitalist or call ourselves the Party of Indignation, ready to fight and defeat the Party of Wall Street and its acolytes and apologists everywhere, and leave it at that.”

Although these are heroic words, I get the sense during question time at the RSA that although there are many who are ready to accept Harvey’s economic analysis, there are many others who do not share even his limited political optimism about the emergence of any such anti-capitalist movement. So when I get him alone I press him further. Wasn’t it true that many of the people he described as possible subscribers to some form of anti-capitalist alliance had little in common but their own parlous situation? History hardly suggested that such powerless groups could effect change on their own.

“I’m not sure that’s true. Who produced the Paris commune? A great part was played by precarious workers, by people from the construction trades. What is true is that it’s very difficult to find organisational forms for people who have no secure job. That’s why in the US we see fewer and fewer people interested in forming unions and more and more people forming covert unions as human rights organisations. If you formulate yourself as a human rights organisation you’re not subject to the labour laws. A human rights organisation can organise temporary workers and yet say, ‘we’re not a union’. They’re also doing that with the homeless. I work for an organisation called Picture the Homeless, which is actively talking about occupying one of these new condominiums and putting all the homeless there.”

Over the course of my meetings with David during the brief time he spent in the UK publicising his latest book, I’d been struck by the oddity of an academic from an American university – albeit one born in Britain – raising the flag for Marxism. His reception here had been, by his own admission, more than favourable. But how did his lectures and books go down in the States?

“How does it go down in the main media? The answer is total silence. It’s very very difficult to get any reviews of my work. But I have to get used to it. I’m under an iron ceiling. Working away in the basement. A bit like the Victor Hugo story. I’m working away at subversion in the sewers.”

Could he even use the term Marxism publicly without risking ostracism? “It’s very difficult. There is an industry called Fox News which is busy saying that Obama is a Marxist. It’s a long legacy of McCarthyism. We don’t recognise how seriously McCarthyism affected the country and how difficult it has been to recuperate from those events back in the 1950s.”

But there were places where he could talk freely? “There are socialist workers’ parties and there’s a revolutionary communist party. They have a bookstore in New York and I sometimes go and talk there. But there’s quite a re-evaluation of Marx going on. Thirty years ago it was a very dogmatic and wooden thing. Now it’s a more open arena of discussion and debate. So, in that sense I’m hopeful that another Marxism, another communism, is possible.”

But even if it was true that Marxism was now more readily debated, there surely hadn’t been any reduction in the public attitude to its corollary, to its atheism?

“Do you know what the largest growing religious group is in the States?” he asks me. “The Mormons?” “Atheists. There’s been a huge surge. I don’t know if you noticed this but Obama in his inaugural address mentioned all the religions and included atheists. For the first time ever. And he knew what he was doing. Because a lot of independents are also atheists. There is even an atheist movement beginning to emerge. Religious fundamentalism is alarming but it is in a minority position. Most religions have a radical left wing as well as a radical right wing and the idea that religion is simply conservative in the US seems to be very misplaced. There’s a wing of the evangelicals that’s saying we have to do something about social inequality and global warming. So the evangelical movement is not homogeneous at all.”

In the last minutes we have left together before he is bustled off by his energetic publicist to an engagement at the ICA, I thank him for his lectures and congratulate him for having, at the age of 75, so much more evident enthusiasm for his subject than many younger academics. This prompts a final question. Although I know that his own City University of New York has a reputation for providing something of a safe haven for radical thinkers, wasn’t he now threatened by the increasing ways in which American universities, like their British counterparts, were becoming more managerially inclined, more closely integrated with big business and the state?

“Well, yes. And the threat comes in two ways. One is directly by simple outright repression. But more significant is the threat posed by the present demand for academics to bring in money. I had a dean saying to me that I wasn’t bringing in any money. You’re worthless, he said, as far as we’re concerned. So I asked what I was supposed to do. Was I supposed to set up an Institute of Marxist Studies funded by General Motors? And the dean said, ‘Yes, that’s a good idea. I’ll support you if you can do that.’”

He was still chuckling as he made his way out to the waiting taxi.