Whether it's boxing or being blonde, racial identity or small town adultery, the wise and prolific Joyce Carol Oates has rightly earned a reputation as the chronicler of America's conscience. And that's why this disjointed little novella comes as such a shock. Taking a shortcut through a deserted park after a party, Teena Maguire is brutally gang raped in front of her twelve-year old daughter and left for dead. The first cop to arrive at the scene is John Dromoor, profoundly affected by the horror he witnesses despite having been desensitised during his spell in the Gulf War.

As she struggles for her life in hospital and then prepares to face the ordeal of the courtroom, Teena is seen entirely from the outside - a cipher of suffering without a point of view. Instead, the narrative shifts between the perspectives of the quietly outraged Dromoor, the dumbly amoral and dehumanised perpetrators, Teena's excluded lover and, in uncomfortable switches to second person, the young girl Bethie.

This is a bleak and unforgiving dissection of American values. The families of the gang of rapists hire a super-lawyer who expertly discredits the victim and creates alternative justifications for the defence: she led them on, she took money for sex, she was willing, the violence was nothing to do with them.

The rapists, ill-educated and mostly with records of past offences, were too high on crystal meth to remember quite what they did but are eager to rework their versions in accordance with the meta-narrative of their legal representative. They are America's white trash: without conscience, sensibility or purpose, they flaunt their fading libidos in the face of no future.

One of them, Fritz Haaber, whose employment has so far consisted of "every kind of degrading shit job you could imagine", thinks he could probably make a good lawyer. "These guys really made money for just shooting off their mouths. It was mind-fucking."

The author implies that she rather agrees with him. We have arrived at a legal system where performance and lies are the arbiters, and where big fees have replaced justice or compassion. As the great lawyer explains to his clients: "There are two sides to every story. The winning side, and the other."

Oates's solution is chilling. Dromoor, the man of law, turns vigilante and wipes out the victims one by one. There is no mystery or suspense here, nor any notion of conflict. His logic is presented as inalienable, and it works. He gets away with it. Teena and Bethie are somehow restored to normal life, though the account of their redemption is too allusive and glib to carry any conviction.

This is not a love story. There is no love, nor any other discernible emotion except for inadequately evoked frissons of fear and an undertow of despair. I can't help wondering whether the inappropriate subtitle was added to make the novel more palatable for the UK market, where it has only just surfaced, two years after it was published in the States. If so, the ploy is unsuccessful, merely adding to the dishonesty and crassness of a morally flawed idea. As a huge admirer of this author, I can't help feeling something, somewhere, has gone very badly wrong.

Off the Boil

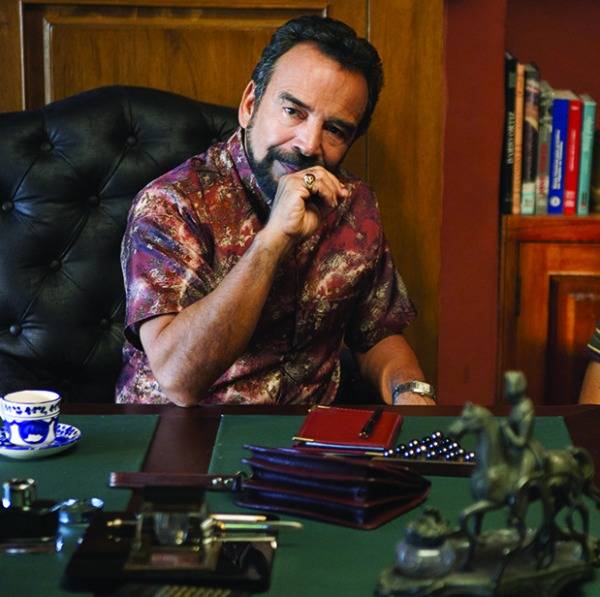

Sally Feldman chokes on her (Joyce Carol) Oates