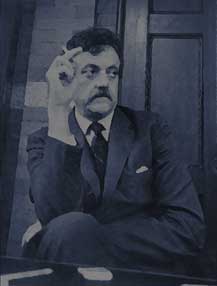

‘Maturity is a bitter disappointment for which no remedy exists, unless laughter can be said to be a remedy.”

The line is from the 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, who died on April 11, aged 84. Though he puts it into the mouth of his character Lionel Boyd Johnson aka Bokonon, the founder of a new religion, it’s fair to assume that this reflects Vonnegut’s own view. His published work certainly suggests as much: more than twenty books, novels, short stories and non-fiction, all suffused with a weary melancholia leavened with great jokes and folksy philosophy.

Vonnegut was Honorary President of the American Humanist Association, and certainly a humanist, though of a rather special kind. For a start he disliked the word “humanist”. Indeed, he seemed scornful of any kind of “ist”, though not of the human search for meaning. Bokonism, the religion he invents, combines a savage parody – the first line of The Book of Bokonon is “All of the things I am about to tell you are shameless lies” – with an acute understanding of why people have found it necessary to comfort themselves with untruths, or striven to find a “clean corner” in a “messy world”.

Vonnegut was Honorary President of the American Humanist Association, and certainly a humanist, though of a rather special kind. For a start he disliked the word “humanist”. Indeed, he seemed scornful of any kind of “ist”, though not of the human search for meaning. Bokonism, the religion he invents, combines a savage parody – the first line of The Book of Bokonon is “All of the things I am about to tell you are shameless lies” – with an acute understanding of why people have found it necessary to comfort themselves with untruths, or striven to find a “clean corner” in a “messy world”.

For Vonnegut religion, like all things man-made, was ridiculous when it wasn’t actively evil, and his writing indicates that this was his view of most ideologies, organisations and people. He coins the word granfalloon for ridiculous institutions from the General Electric Company (for whom he worked) to the Communist Party to “any nation, anytime, anywhere”, which attracts his playful scorn. This scepticism of big institutions and big ideas went hand in hand with his view of humanity and human endeavour: people are insignificant creatures busily constructing fantastical ways of holding at bay the inevitable pointlessness of existence. Life, in the words of Kilgore Trout, his sci-fi writer alter-ego, is “a crock of shit”. To those who argue that there is an ultimate purpose or plan he might offer the dedication from his 20th novel, Timequake: “All persons living and dead are completely coincidental.”

Yet Vonnegut injected a warm, almost sentimental, love for human beings into his bitter horror at man’s capacity for inhumanity and his abhorrence of the manifold methods of torture, murder and madness produced by modernity. And that is perhaps why his savage asides are also so mordantly funny. In Timequake, for example, he mentions the nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, who developed the Soviet bomb: “His wife was a paediatrician. What sort of person could perfect a hydrogen bomb while married to a child-care specialist? … ‘Anything interesting happen at work today, Honeybunch?’ ‘Yes. My bomb is going to work just great. And how are you going with that kid with chicken pox?’”

Vonnegut would return time and again to one almost unspeakable atrocity: the fire-bombing of Dresden, which he experienced first-hand as a prisoner of war in that city and which was the subject of his first hit novel, Slaughterhouse-5 (1969). And yet in the preface to Mother Night (1962) he manages to dismiss even this horror with his characteristic offhand cynicism: “It was the largest massacre in European History, by the way. And so what?”

Though playful and very funny, Vonnegut was always powered by an underlying seriousness. He wrote frequently about his melancholic upbringing in German Indianapolis, which left him with a “deep-boned sadness”, fuelled no doubt by his mother’s suicide. He attempted it himself once and wryly referred to his own weakness for filterless Pall Malls as “a classy way to commit suicide”. He realised that life was, if anything, contingent. He may have fought the Nazis but, he once suggested, if his parents had stayed in Germany who can say that he wouldn’t have become one himself, “bopping Jews and gypsies and Poles around, leaving boots sticking out of snowbanks, warming myself with my secretly virtuous insides”.

Moral superiority repulsed him yet his entire oeuvre is a fiercely moral edifice, designed to goad humanity into overcoming its dreams of mastery and accepting the limitations, the delicious ironies and the simple suprisingness of this life. He aspired, as he had the American Ambassador aspire in Cat’s Cradle, to reducing “the stupidity and viciousness of mankind”. Of course, he always denied being a moralist, dead-panning to the end. Here’s how he describes Mother Night: “This is the only story of mine whose moral I know. I don’t think it’s a marvellous moral; I simply happen to know what it is: We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.” Then he goes on to find another: “When you’re dead you’re dead.” ■