Our understanding of biology has undergone a remarkable transformation over the last 150 years. Not only have Darwin’s ideas given us a theory of how all life and its extraordinary variation have evolved, but cells have been discovered. They are the key to all life.

Our understanding of the cells themselves has also been transformed by the application of chemistry and other techniques. We now know much more about how cells function. A major step was the identification of genes and discovering that their function is to code for proteins – real miracle workers in the cell. All this provides excellent evidence for science being a special kind of thinking, which is prepared to go against common sense. There is no common sense in the idea that small random variations underlie the evolution of all life or that we are no more than a society of cells who develop from one single cell, the fertilised egg.

Our understanding of the cells themselves has also been transformed by the application of chemistry and other techniques. We now know much more about how cells function. A major step was the identification of genes and discovering that their function is to code for proteins – real miracle workers in the cell. All this provides excellent evidence for science being a special kind of thinking, which is prepared to go against common sense. There is no common sense in the idea that small random variations underlie the evolution of all life or that we are no more than a society of cells who develop from one single cell, the fertilised egg.

Many of these discoveries have important implications for human health and this has often been a motivation for the research. However, only in special cases are humans good experimental subjects, moral issues aside, since they breed very slowly and are so large. The history of these remarkable achievements has depended very heavily, then, on model organisms, and that is what this book so elegantly describes, together with the complex lives of the scientists who did the work.

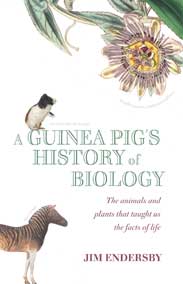

A special feature of the book is the importance Jim Endersby, an historian of science at Sussex University, gives to the role of research on plants. Much attention is given, for example to the passionflower. Darwin collected two unfamiliar species when he was in the Galapagos; he wished to investigate their fertilisation and was puzzled by their aversion to self-fertilisation. He also wanted to understand how natural selection had created this specialised climbing plant. His plant studies also affected his thinking about sex.

How the units of heredity, genes, were finally identified is another good, though complex, story. No one predicted that they would be tiny and located on chromosomes and merely code for proteins. Darwin, for example, thought that such units – then known as gemmules – were distributed throughout the body, and characteristics that were acquired during an organism’s lifetime could be inherited. It was only later in the 1880s that August Weismann announced that sperm and eggs determined an organism’s form and that the environment had no influence on them.

A key influence on this was Gregor Mendel’s study of inheritance in peas. But as Mendel was a simple monk in Austria his discoveries were largely ignored. Endersby reports that Mendel sent a copy of his paper to Darwin, but the eminent biologist neglected to read it.

Small events could have big effects in the advance of science at that time, with many a wrong turn along the way. Dutch botanist Hugo DeVries used yet another plant, the primrose, to study changes that could provide the mechanism for evolution. Did evolution go slowly with small variations, or by leaps?

DeVries thought he found the answer in the emergence in his plants of new species of primrose. Also this was the first organism subject to radiation to bring about changes. But there was something odd about the behaviour of the primrose and its popularity fell into decline

Then attention became focused for many on the fruit-fly, Drosophila, which had many advantages as a research object including size and a rapid breeding cycle. The American Thomas Hunt Morgan was a key figure and identified the linkage of mutations with chromosomes. Morgan won the Nobel prize for Physiology in 1933 for his work on mutation in the fruit-fly.

Endersby emphasises that in addition to being a researcher Morgan was also a lecturer, first at Columbia and then as the Biology Chair at Caltech. He was able to attract and retain talented students to aid his research, a valuable lesson for those who would wish to separate teaching from research in our universities.

In addition to plants small mammals have proved important model organisms, most often used on studies that relate to human health. Both the guinea pig and the mouse are heroes of scientific discovery, though their use has, of course, raised ethical issues about animal experimentation. The discovery of Vitamin C came from guinea pig studies. Humans have, perhaps thankfully, seldom been used as experimental organisms, the exception being the work initiated by Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton. Galton measured human attributes from Hottentots’ buttocks to mental abilities. It was he who promoted the improvement of the human race by artificial selection which led, alas, to eugenics.

Though this is a fascinating and beautifully written book, as a developmental biologist I do regret that there is nothing on how the fruit-fly and amphibia have contributed to our understanding of how embryos develop. But this is a minor quibble, intended merely to suggest that Endersby has started, though not completed, the work of honouring these apparently humble organisms that continue to teach us the facts of life. ■

A Guinea Pigs' History of Biology is published by William Heinemann