‘Bite my ear. Push back my hair. I have learned to unbutton you so swiftly. All, in my mouth, sucking. Your fingers. The hotness. The frenzy... The womb sucks, back and forth, open, closed. Lips flicking, snake tongues flicking. Ah, the rupture – a blood cell burst with joy.”

No one knew better than Anaïs Nin the essence of the kiss: that it’s the meeting of mouths, of flesh pressing into flesh, electrical charges and sizzling fire. It’s about bodies, and bodies pleasuring each other: earthy, lustful and passionate.

And yet, this most carnal of acts is also deeply associated with religion. Christianity in particular has infused the kiss with spiritual meaning, sanctifying it into chastity in the quest to suppress our animal urges. The more the kiss is entwined with godliness the more it is separated from sexual, human love.

And yet, this most carnal of acts is also deeply associated with religion. Christianity in particular has infused the kiss with spiritual meaning, sanctifying it into chastity in the quest to suppress our animal urges. The more the kiss is entwined with godliness the more it is separated from sexual, human love.

Kissing first began to be appropriated by religion through its identification with breathing.

Breath, as the embodiment of life, is widely thought to represent the soul, so the exchange of breath implies a fusion of spirits, as in the Eskimo custom of nose-rubbing. In Hindu philosophy, the kiss represents a reintegration of the two halves of the human soul through the mingling of two breaths, while Plato refers to the notion that the god breathes his own divinity into the souls of some heroes.

Christianity took this connection to the extreme, with the idea that God created man by breathing into him. And that the Holy Spirit penetrated the Virgin Mary through breathing into her, or kissing her. An early Christian icon depicts the Holy Ghost as a dove, kissing the dying figure of Jesus who himself had breathed the Holy Spirit into his Apostles.

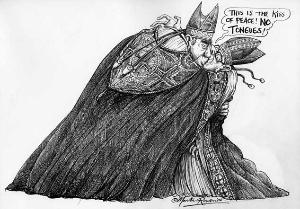

So the kiss began to assume the status of a conduit to holiness, invested with heavenly properties. Christians will kiss the foot of the Pope or the ring of the Bishop not merely as an act of reverence, but in order to absorb their godliness. Just as pagans will kiss their idols, Christians will kiss relics and holy images to enliven the hotline to divinity. Kissing the cross is an especially holy act, so much so that kisses have eroded much of the right foot of a statue of St Peter in St Peter’s Square. Jews kiss their prayer books and the sacred scrolls of the Safeh Torah in order to show respect for the word of God but also to connect with his greatness.

The magic power of the kiss is a motif woven through myth and folklore: it’s a kiss that awakened Sleeping Beauty, that turned the frog back into the prince and that quickens the Blarney Stone into granting the gift of the gab. And the assumption that the kiss has the power to convey something greater, something beyond its intrinsic nature, is itself a diminishing of an essentially human gesture.

In his magisterial study The Kiss Sacred and Profane Nicolas Perella demonstrates how the kiss came to symbolise spiritual as opposed to physical union.

“It is true that this idea of a fusion or union of two in one is also symbolised or even ritualised by sexual union... The kiss, however, has the advantage of expressing the concept with or without erotic overtones and, in either case, of doing so spiritually. This is owing to the unique value associated with the idea of breath.”

And this value led to the central Judeo-Christian idea of the kiss of peace, the holy kiss, the kiss symbolising harmony and reconciliation and love. In the Jewish tradition the kiss was a pact between Israel and God, a promise of Messianic redemption. In Christianity, it became the unity of believers in their adoration. Following the instructions of St Paul and Augustine, early Christian congregations would be exhorted to kiss, mouth on mouth, as part of the Eucharistic communion.

All of these devotional contortions serve an obsessive desire to separate body and soul, despite repeated references to the kiss as a fusion of the two. A basic assumption was that there could be no confusion between carnal and divine love, because their objects were so separate. Yet Christians had a lot of trouble keeping the kiss holy because there was always the hovering threat of lust, and the danger that believers might just enjoy their sacrament too much.

At the same time, though, Christian commentators have routinely plundered the language of erotic passion as a metaphor for the experience of union with God. The more explicit the imagery, the more holy the intent. And the most potent example of this displacement is the Song of Songs, attributed to Solomon, and suffused with some of the most beautiful erotic poetry ever written:

“How fair and how pleasant art thou, O love, for delights!

“This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes.

“I said, I will go up to the palm tree, I will take hold of the boughs thereof: now also thy breasts shall be as clusters of the vine, and the smell of thy nose like apples;

“And the roof of thy mouth like the best wine for my beloved, that goeth down sweetly, causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak.

“I am my beloved’s, and his desire is toward me.”

With admirable insouciance, Christianity has managed to deny the poem’s sexual intent, interpreting it instead as a homage to godly love.

As Perella puts it: “It is worthy of note that the Song of Songs, which supplied the mystics with most of their erotic imagery, was almost unanimously considered by the Christian exegetes to be pure allegory; that is, no literal or profane meaning was to be attributed to its text. Here the cleavage between the letter and the spirit is absolute and everything is accommodated to the latter.”

So even the most seductive passages of the Song are interpreted as mere metaphors for a higher form of passion. It does seem absurdly farfetched to deny the rich sensuality of images like lips dripping with honey and honey and milk lingering under the tongue. But then, there has always been a powerful correlation between erotic and heavenly ecstasies, ever since St Teresa of Avila shuddered with orgasmic pleasure at her visions of an angel plunging his golden spear into her heart until it penetrated her entrails.

For Richard Dawkins, this association is a function of evolution. In The God Delusion he suggests that the irrationality of religion could be a by-product of the mechanisms built into the brain by selection for falling in love, and that the symptoms of religious mania and sexual love are startlingly similar. He quotes the testimony of the philosopher Anthony Kenny, who was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest and recalls the joy he felt at the laying on of hands to celebrate mass:

“It was touching the body of Christ, the closeness of the priest to Jesus, which most enthralled me. I would gaze on the Host after the words of consecration, soft-eyed like a lover looking into the eyes of his beloved.”

But it’s not just that divine revelation can produce powerful sexual feelings. Conversely, sexual passion itself can be so intense that it can be mistaken for metaphysical rather than earthly bliss. In Transcendent Sex, Jenny Wade interviews 92 people who claim some other-worldly experience of sexual intimacy. Many describe the sensation as religious, making them feel at one with God or with the cosmos.

This reverse effect, whereby sexual rapture is transmuted into the divine, informs Christian interpretations of The Song of Songs. You wouldn’t think there could be much doubt about the opening line: “Let me kiss him with the kisses of his mouth.” But the willing bride welcoming her lover to bed, by divine sleight of hand, becomes in the Christian canon the Church opening its arms to its spiritual groom, or God. It’s a development of the rabbinical interpretation of the union as that between Yahweh and the community of Israel. For Christians, the woman becomes a vessel, a symbol of the temple of the Lord who must open her doors to Him.

And this appropriation of the kiss justifies one of the worst effects of organised religion: the subordination of women. For if the conjugal union of man and wife symbolises the spiritual union between Christ and the Church, then it also dictates a more earthly power balance. As St Paul so famously dictated:

“The man is the head to which the woman’s body is united, just as Christ is the head of the Church... and women must owe obedience at all points to their husbands, as the Church does to Christ.”

And so the Church is able to evidence sexual pleasure as proof of a natural order whereby men are closer to God than women and thereby have license to dominate and rule them. Kissing transmutes from human delight to human reverence; worship of sexual joy to worship of the divine.

Even when romantic love began to be recognised as a secular activity the kiss never completely shed its mystical associations. In the early mediaeval romances such as Lancelot and Guinevere, Tristan and Iseult and Pyramus and Thisbe, forbidden and sanctified love are intertwined. The kiss of lovers is harnessed as a symbol of fate, of moral turpitude or virtue, as a heralder of both life and death.

And the kiss as a mark equally of earthly sin and Christian divinity reaches its apotheosis in Dante’s Divine Comedy. The ideal of virtue and godly love is the unreachable Beatrice, who is the object of the quest and the incarnation of purity. She is never sullied by human contact, unlike the fallen lovers Francesca and Paolo, who linger in Purgatory, united in eternal hell as a result of their impure transgression. And the moment that sealed their fate was when they surrendered to licentious desire with a kiss.

Four centuries later, the mystical properties of the kiss still linger. That most famous kiss in western art, Rodin’s magnificent sculpture, was inspired by Francesca and Paolo and carries all the mystical associations of their fateful embrace, mingling anguish, passion, sin and beatitude.

Even the most enlightened of authors have been in thrall to these transcendental claims.

In his Confessions, Rousseau describes his kisses with Mme d’Houdetot as having the character of a sacred rite. In his short story The Kiss Chekhov describes how a mistaken embrace nonetheless has a transforming effect on an awkward and hitherto unnoticed young man.

And in The Sorrows of Young Werther Goethe produces a paean to doomed romantic love, where adoration of the untouchable Lotte is laced with the desire for immortality. Werther’s desperate finale is presaged by the one kiss his beloved grants him before death.

Popular romantic fiction has always relied on the magic of the kiss as a principal signifier, routinely following the trusted formula that a happy ending will be marked with a kiss, and a sad tale will begin with one. Invariably the kiss dictates the action and the destiny, just as it does in fairy tales and in devotional literature. Meanwhile, popular song is full of references to the secret in his kiss, the kiss as honey and sugar, kisses sweeter than wine, in unconscious tribute to the Song of Songs and all that it unleashed.

And what is most significant about all the classic film clinches, from Rhett Butler’s ravishing of Scarlett O’Hara to the crashing waves in From Here to Eternity, is the consistency of the pose. Just as in Rodin’s iconic couple, the man is always masterful, the woman surrendering. He is the lord and she the receiving vessel. That casual misogyny, even now, is the legacy of the hijacking of the kiss by religion.

If we are to reignite its flames, recognise the transformational power of the kiss but also reclaim the equality of the union it implies, humanists must wrest its meanings back from the god brigade. So light those candles, serve up the oysters and slip into something silky. And as you melt into a sensual, rapturous, honeyed atheist embrace, you’ll be affirming the eternal verity: that the sacred is human and sexual ecstasy is earthly paradise. ■