An enthusiastic young woman called Nicola rings up to ask me if I'd like to speak to the employees of her cement company about something she calls “emotional intelligence”. As she’s offering me slightly more for my services than the going rate for marking several thousand Open University assignments I decide to play it safe and stick to what I know.

“What sort of cement exactly?” “Specialist cement”, she tells me. “Specialist cement?” “That’s right. We specialise in the cement that goes into runway concrete. Have you ever thought how quickly that has to dry? Imagine a hole in the main runway at Heathrow. You couldn’t wait for five hours for that to dry, could you? That’s where we come in.”

“What sort of cement exactly?” “Specialist cement”, she tells me. “Specialist cement?” “That’s right. We specialise in the cement that goes into runway concrete. Have you ever thought how quickly that has to dry? Imagine a hole in the main runway at Heathrow. You couldn’t wait for five hours for that to dry, could you? That’s where we come in.”

I’m about to ask why all cement isn’t specialist cement and about how this might alleviate the current housing crisis when she pulls me back to “emotional intelligence”. “Is that one of the subjects you cover in your lectures? “Oh yes,” I say, “it’s becoming increasingly important in the modern workplace. Increasingly important.” She tells me that the name of the hotel near Rugby where the cement conference will take place and we agree a date for the conference call when she and her CEO can chat further about my contribution.

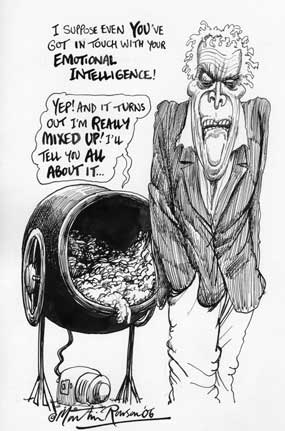

It only takes a moment on the Internet to learn that emotional intelligence has suddenly become one of the key elements of working life. It is indeed “increasingly important”. I even find one report on universities which authoritatively declares that emotional intelligence now counts for far more in the academy than mere intelligence. There’s a list of key concepts. First off is “self-awareness”. This doesn’t simply mean keeping your eyes open in case you accidentally fall into the cement mixer, but an ability to be “aware of your own emotions and know how to unlock your own triggers”. And that’s only a beginning. Once I become aware of my own emotions I have to manage them “so as to get the best out of them” and then “build on my self-awareness so as to tune into others”. Most of all I have to develop my ability to “read other people’s emotions without their telling me what they are”.

None of this is good news. I certainly don’t want to be any more aware than I already am of my own emotions. One more ounce of awareness and getting out of bed every morning would become totally impossible. Neither have I the faintest interest in being able to read other people’s emotions. Much of my life is spent trying to avoid any knowledge whatsoever of how others might be feeling. Indeed, so often do I find myself enmeshed in conversations with people who want to tell me all about their emotions that I’ve begun to take precautionary measures. As soon as anyone begins to talk at length about their feelings and the dismal state of their current emotional life, I cut them short with an unequivocal opinion. I never prevaricate. Never spend a moment weighing up the pros and cons. I come straight out with black and white advice. Leave your wife this instant. Stop having your clandestine affair immediately. Marry your mistress. Go home this very night and tell your children that you’re gay.

It has lost me some friends: Mike Leftwich has never fully forgiven me for suggesting that he should immediately gratify his transvestite feelings by turning up in full drag for his wife’s surprise birthday party. But on the whole it means that I’m now surrounded by people who are no more likely to bore me with news of how they feel than to suggest that my life might be filled with sunshine if I spent more time thinking about baby Jesus.

It’s a reciprocal arrangement. Whenever I’m around, everyone knows that feelings and emotional relationships are off the agenda. I even have a small card fixed to my home telephone which bears this admirable injunction from Goethe: “It is always better to enchant friends a little with the results of our existence than to sadden or worry them with confessions of how we feel.”

All in all, then, I’m not too surprised to find that when I complete the “emotional intelligence quiz” which is offered by one Internet site I emerge with an overall score of just two. According to the specialist in emotional intelligence who compiled the quiz this means that I am in Category D: “Emotionally subnormal”.

Not that I’m going to let all this get in the way of my cement address. As long as Nicola feels that a gaping hole in the Heathrow runway is more likely to be ready for the first morning flight if the cement layers are in tune with each other’s emotions, that’s good enough for me.

I’ve already drawn up my eight PowerPoint slides and my six-step guide to action. I even have an opening joke. “Have you heard the one about the man who fell backwards into his cement mixer and got behind in his work?” That should unlock some triggers. ■