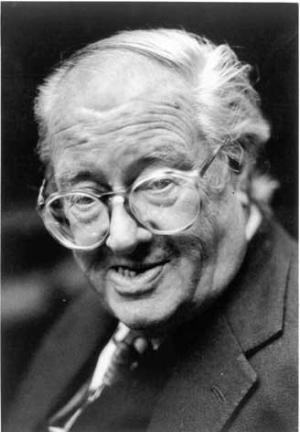

Like many other readers of this journal, I have scores of reasons to be grateful to John Mortimer. Time after time, when politicians have suddenly seemed more unprincipled than ever and priests and bishops more hypocritically risible, he’s suddenly cropped up on radio or television and delivered, in his endearing, slightly querulous, high-pitched voice, a wonderfully unqualified blast of good libertarian sense. Even when he’s only been invited into the studio to discuss the plot of his latest Rumpole novel, he’s somehow always managed to make room, in even the most banal interview, for a clutch of telling rational comments on one or other of his favourite topics: penal policy, drugs, censorship, sexual mores, civil liberties.

I suspect we sometimes overlook the persistent courage of his interventions into so many public debates because his remarks never seem to attract the type of dismissive editorial outrage which so often greets the expression of very similar views by such other public sceptics as Jonathan Miller and Richard Dawkins. Even his natural opponents recognise that there is something in his cantankerous refusal to toe the line which deserves to be honoured and preserved. But that comes at a cost. However much he may dislike it, he can no longer successfully resist the lazy journalistic insistence that he has become a grand old English treasure.

I suspect we sometimes overlook the persistent courage of his interventions into so many public debates because his remarks never seem to attract the type of dismissive editorial outrage which so often greets the expression of very similar views by such other public sceptics as Jonathan Miller and Richard Dawkins. Even his natural opponents recognise that there is something in his cantankerous refusal to toe the line which deserves to be honoured and preserved. But that comes at a cost. However much he may dislike it, he can no longer successfully resist the lazy journalistic insistence that he has become a grand old English treasure.

None of this meant that I felt exactly confident at the prospect of interviewing John for New Humanist. What possible new revelation or startling insight could I hope for from such a very public personality, whose life is already an open book, or rather two dozen open books, in which he has relentlessly chronicled his wives and children, his personal likes and dislikes, his illnesses and afflictions, his enduring political and religious beliefs?

And many of these confessions have been reworked over the years for new audiences, including the current revival of Voyage Round My Father, his vivid and moving account of life at home with his blind, irascible, free-thinking father.

Indeed, the more you read of Mortimer, the novels and the autobiographies and the plays, the more you feel that you are living in a closed system: a delightful collection of strange encounters and amusing anecdotes and eccentric characters that is about as incapable of being knocked off course as the plot of one of his beloved Dickens novels.

I felt desperate enough to ring up an old friend who I knew had recently spent many hours talking to John. Was there any way I might get beyond the familiar revelations? She could offer little comfort. “If you ask him a question that is awkward or out of the ordinary he will adopt one of two strategies. He will either seize on a word which prompts a familiar anecdote or distract you with the offer of another glass of champagne.

“Oh, and one other thing. There is absolutely no way that you can ever know when he is telling the truth.” That I knew. Across the top of my notes in bold letters I’d already recorded the cautionary words of his daughter Emily: “He always tells a lie if it makes things more interesting”.

But on my journey out to the famous old house near Henley-on-Thames which John inherited along with a complete philosophy of life from his barrister father, I found some little consolation in the thought that the questions I would be asking on behalf of this magazine were less likely to prompt familiar anecdotes or interesting lies: questions about religion, belief, transcendence, mortality and the possibility of an after-life.

He greeted me with his usual warmth. “Pour yourself a glass. When was the last time we met? Pity about the weather. Are you comfortable there?” I was already thinking how splendid it would be to drink the afternoon away in such fine amusing company. But I knew I had to sit up straight and not allow him to set the mood. There was work to be done. Where were my questions?

I decided to start with God. Was I right, I asked, to regard him as a life-long atheist? Did I correctly remember debates way back in the late 60s when he’d come on television and argued the toss with Malcolm Muggeridge? He looked a little disappointed at this slightly formal turn in the proceedings but was soon into his stride again.

“Yes, it was a programme called Your Witness in which we both called witnesses to testify on our side. I don’t think I won but I do remember Muggeridge calling a wonderful nurse who believed in God and had done incredibly good works in Africa. When I cross-examined her, I said, ‘I suppose if you didn’t believe in God, you wouldn’t have done any of that wonderful work?’ And she had to admit that she would still have done it without any belief.”

He obviously enjoyed such debates. Was that because he could play barrister in public or because he particularly relished arguing about God?

“I always want to talk about God. I love talking about God the whole time. I loved all the television interviews I had with bishops, with Runcie and Hume. I was fascinated by such people. I wish them well. The question I always ask is: if you are an omnipotent, loving God, then why did you allow the Holocaust to happen? And they all have such unsatisfactory replies.

“Runcie, or maybe it was Hume, told me sadly that it was a bit like going up a hill. You always had to get down the other side. Something odd like that. But the most satisfactory to me was Muggeridge who said that God was the great Shakespeare of the sky. He was an author and if you were an author then you had to have bad characters in your plays.

Graham Greene was another. We used to have lunches in Antibes and he was not nearly as religious as he sounded. As a betting man he used to say that it was odds-on that there was a God. But he wouldn’t put it any higher than that. And he really wasn’t tedious about it.”

John was talking to me from behind the desk in the little room to the side of his cheerfully jumbled house where he does all his writing. I could see occasional bursts of sunshine through the window and wondered whether we both might be more at ease in his beloved garden.

“But in recent years John has been hit by what he calls “a landslip of physical afflictions” and I suspected that even the simple act of getting up out from behind the desk and hobbling the few yards to where his pacey electric wheelchair was parked outside the kitchen door might prove too exhausting. So I tried to forget the slightly intimidating desk and the fact that I was putting questions to a man with a formidable legal reputation for interrogation.

“I wonder,” I said, stepping carefully, “I wonder if your lifelong disbelief in God has shown the slightest, just the slightest, sign of wavering as you’ve got, well, nearer to death. Does the thought of nothingness concentrate the mind? Make a difference?”

“No, nothing happens. Nothing at all. Nothing. I was always really proud of my father because he never believed in God. He never did. Even after he’d gone blind and was approaching death, he never wavered in his non-belief. My father was a Darwinian. His God was Darwin. And Huxley was his John the Baptist. Darwin’s prophet.

“He thought the creation story was ridiculous. He used to say ‘Nobody could create a horse in seven days let alone the universe.’ And my mother didn’t believe in God. She was a sort of Fabian new woman who thought it was a load of rubbish. I’ve never had any religious instinct at all.”

“Not even at school?”

“Not even at school. When we had to say our prayers I’d kneel down and count up to a hundred and then get up and go to bed. It simply never occurred to me that it was true”.

I was beginning to feel not unlike a prospective diner who’d arrived at a restaurant and been casually but definitively informed by the head waiter that nothing on the menu was still available. Hadn’t John ever been plagued by any of my adolescent doubts and questionings, my occasional sense that was something more to life than the material world, my recurrent feeling that some explanation was needed for what one could only describe as the transcendent moments of our existence? Not really.

“Any moment in time can be transcendent. That doesn’t make it religious. In the living present there can be moments of great significance. That is the best we can have. And I think that is very good. And if you consider the great writers, Chekhov, Dickens, Shakespeare, they are great because they celebrate that moment of living. It doesn’t need any unearthly assistance. That only diminishes it. If you think that life is just another testing ground for eternity, a batting practice, it trivialises everything.”

The friend who’d marked my card about John’s capacity for not answering awkward questions had also suggested that he was uneasy with self-examination. It was, of course, true that he’d laid out his life in great detail in his books and was also quite an expert at using self-mockery to defuse any notion that he might ever take himself or any of his ideas too seriously.

“But there were places where he didn’t wish to go, areas he strenuously avoided. And perhaps the only person who’d seriously dared to investigate such evasions was his unofficial biographer, Graham Lord, in The Devil’s Advocate. It was Lord who was the first to reveal that Mortimer’s affair back in the early 60s with the actor Wendy Craig had resulted in the birth of a son, Ross, whom Craig’s husband had brought up as his own. (The happy reunion between Ross and his father pre-occupied the tabloids for days.)

Some reviewers regarded this revelation and others about Mortimer’s affairs and biographical inconsistencies as seriously denting his reputation.

In the Daily Telegraph, for example, Christopher Silvester described the Mortimer who emerged from Lord’s book as “a sometimes cruel, insecure, grasping, self-satisfied man with loins of clay”. But the majority followed the line taken by Caroline Boucher in the Observer, who thought that Lord had tried far too hard to rake up any disagreeable fact and ended up with a book that seemed merely spiteful.

What effect, she asked, would such a book have upon Mortimer’s reputation? “Will Rumpole fans go out and burn their worldwide fan club cards? Does Voyage Around My Father become a lesser play? Of course not. There’s a danger tilting against some windmills and, in the case of this national monument, part of the reason he’s up there is that he’s never ever hidden his awful habits”.

I decide to quote from Lord to see if it would rumple John’s easygoing atheism. “Your unofficial biographer says that ‘you grew up to hate God and find it amusing.’ Is that fair?”

“No, it’s not. I have absolutely no conflict with religious people. I think Christianity is a terrifically good thing. I think it’s the best series of myths that you could possibly have. I have enormous respect for religious people. I love religious art. Everything. I certainly don’t hate God because I don’t think he’s there.

“If he were there, I think I should hate him. And if I should find him personally responsible for all the miseries of the world, I would find myself very cross with him. But as he isn’t there I don’t have to bother.”

“So you don’t feel any empathy with someone like Richard Dawkins who regards religion as an affront to rationalism, something which has to be rejected in the name of science?”

“Not at all. I mean he goes around preaching about it all the time”.

I try another tack in an attempt to test his certainty. “But don’t you ever worry that you might succumb to a deathbed conversion? At the moment you seem to have all the wonderful assurance of David Hume – you’ll remember that as he lay dying, Boswell asked him whether or not he thought it possible that there might be a future state where would account for all our sins, and Hume gently said, ‘Tis possible that a piece of coal put upon the fire will not burn, but to suppose so is not at all reasonable. It is a most unreasonable fancy that we should exist forever.’”

“No, I can’t accept the idea of an immortal soul. All those people in heaven. It would be like being in a crowded Trust House Forte.”

“So you don’t have any notion of preparing for death?”

“I don’t want to die, but I don’t want to turn to God. You have to go on living as if you were living forever. All I know is that I am going to see a bright light. Penny (his present wife) had a near-death experience and saw bright lights and so I know that if that comes, that will be it.”

“But in one of your recent autobiographies, you approvingly quote Montaigne: ‘Being a man who broods – I am just about as ready as I can be when death does suddenly appear.’ Doesn’t that suggest you might have made some preparation?”

“Montaigne wanted death to come upon him when he was digging his potatoes. The real trouble with old age is that it lasts such a short time. Days now seem to be chasing each other like Keystone Cops. You’re afflicted with various things and then by the end you say, ‘Oh Christ, I’ve had enough.’ So much better if they just popped you off in your prime. Death is a matter of slapstick and pratfalls. Only by laughing at old age can you find release.”

Although the last phrase was rather tossed away, I knew from my reading that it wasn’t a casual injunction. Mortimer’s lifelong belief in laughing at serious matters is almost an ideology and springs directly from his passionate love for Byron: his poetry, his extraordinarily exciting crowded life, and perhaps most of all his attitude towards his own deeply held beliefs.

It is Byron’s assessment of life in his Journals which provided Mortimer with the title of his last-but-one volume of autobiography, The Summer of a Dormouse: “When one abstracts from life infancy (which is vegetation), sleep, eating and swilling, buttoning and unbuttoning – how much remains of downright existence? The summer of a dormouse.” And nothing pleases John more than to learn from his reading that the things that Byron cared about most “he spoke of with a throwaway response.”

I suggest to John that this determination to laugh in the face of adversity might be called stoicism, at least in the popular if not the philosophical meaning of the term. “Yes, I think stoicism is an English virtue. Although I think my father was much more stoical than me because he had to put with being blind and still go on being a barrister even if he did sometimes have to release himself with fits of rage. Yes, I think I would like to be thought of as stoic.”

“But isn’t there a danger in that attitude? Some people see that sort of toughness in adversity as almost synonymous with living an unexamined life. You don’t allow yourself to think about what is going on around you. About who else might be hurting or in pain. You simply put your head down and march straight forward. Your father may be an admirable character to you but when he is presented on the stage, you can’t help thinking he’s also a bit of a bugger.”

“Yes, he was. He certainly was. He certainly had his faults. But I don’t know if he’d have been less of a bugger if he’d believed in God. He might even have been worse. I think you find the stoic position best represented in Shakespeare, in the characters that he loved, like Kent. People who accept what their position is and live with it. It doesn’t stop self-examination. There is nothing I don’t examine. I don’t think there is anything I stop at. No.”

But was “acceptance” the right word to describe his attitude to some of the vicissitudes that had overtaken him in recent years? He almost seemed to take a perverse delight in refusing to take care of himself.

So when, at the beginning of his physical troubles, his doctor had asked him if he ever got breathless after exercise, he was delighted to be able to say that he couldn’t answer the question because he’d never taken any exercise in his life. He was also defiantly proud about his determination to go on drinking. (I have personal evidence of his capacity in this respect. Four years ago John took part in a television programme I made for Channel 4 on the nature of celebrity. Part of the package was an agreement that he could enjoy a complimentary meal and drinks at the Groucho club after the recording. “The producer told me later, with barely concealed admiration, that he simply couldn’t imagine how Mortimer and his guests had managed to rack up such an enormous bar bill in such a short space of time.)

Neither does he take any care at all with his diet. “I refuse to spend my life worrying about what to eat. There is no pleasure worth forgoing just for an extra three years in the geriatric ward.”

But perhaps the best concrete evidence of his sheer perversity in this respect was the box of small cigars on his desk. “Do you mind if I smoke?” he’d said early in the interview. “I didn’t know you smoked.” “I only started again because of all the anti-smoking hysteria.”

“You’re determined never to be thought of as a victim?” “That’s right.” “So you can have very little sympathy for those who turn up on radio and television programmes to tell us about their illnesses or their failed relationships or their psychological traumas?”

“I can’t bear the sound of whining. Everyone now seems to be writing and talking about their depression or whining about people not understanding them. The sound of Blunkett is absolutely repulsive. Whining away all the time on every medium. It’s all part of a universal whine. Would you like to go out and see the garden now?”

Although I knew he was never going to admit as much, it was obvious that John was tiring. I needed to tie a neat knot around the conversation. “I understand your father was buried in the local C of E churchyard. Will you be buried there?” “No, I will be cremated.” “But will the funeral service be in the same church?” “I might have a memorial service.”

“Could I provide you with a nice humanist speaker who’d come down for the service and help to celebrate your life?”

“I don’t mind what you do. If you like, I’ll have a full solemn mass.” ■