In the period immediately before and after the First World War, Emil Otto Hoppé was one of the most famous photographers in the world. Two new collections, E.O. Hoppé’s Amerika and E.O. Hoppé’s Australia, to be followed by Germany and England, aim to reinstate him. They demonstrate that he deserves a place alongside figures like the American Walker Evans and the German August Sander in the top rank of documentary photographers.

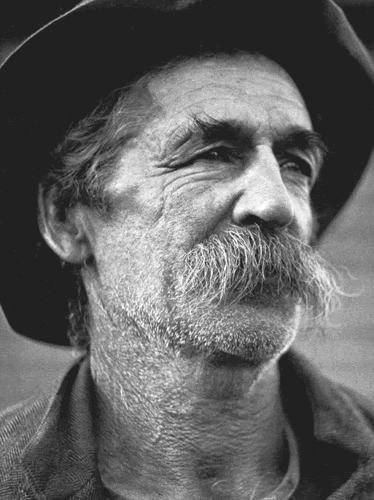

Born into a wealthy banking family in Munich in 1878, Hoppé moved to London in 1900, ostensibly to satisfy his father’s desire that he make a career in finance. But he quickly took up amateur photography with such success that by 1907 he had turned professional. He was soon established as the leading portraitist of his day, displaying acute business acumen in exploiting his impeccable range of social contacts. His celebrity clients included George Bernard Shaw and Enrico Caruso. But, as these books show, his most interesting work lies in the series of lengthy projects he began in the 1920s, taking long journeys to produce photographic travel books for the leading German publisher, Wasmuth.

In dramatic contrast to his society portraits, these images reveal his considerable skill in photojournalism – a term he was among the first to employ. In his autobiography, One Hundred Thousand Exposures, Hoppé writes of an incident which encapsulated for him the thrill and reward of being where the action is. When a hot-air balloon exploded at the Franco-British exposition in White City in 1908 he was the only one with a camera. He sold his exclusive shot to the Daily Mirror. As Philip Prodger writes in his introduction to E.O. Hoppé’s Amerika, Hoppé was among the first photographers to try to capture the essential character and identity of a society through undertaking a detailed photographic survey.

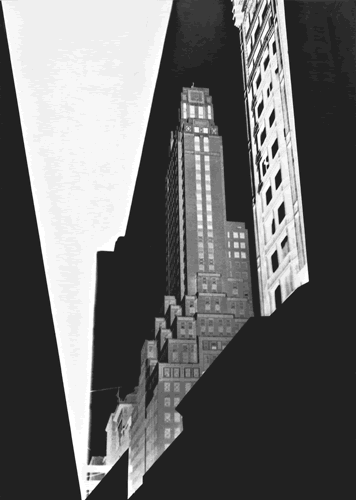

Though he had started out in 1902 using the fashionable soft-focus Pictorialism style of the day, by the 1920s he had begun to embrace modernism, displaying a hard-edged clarity and a stunning grasp of technique that is distinctly contemporary and very evident in E.O Hoppé’s Amerika, originally published by Wasmuth as Romantic America in 1927.

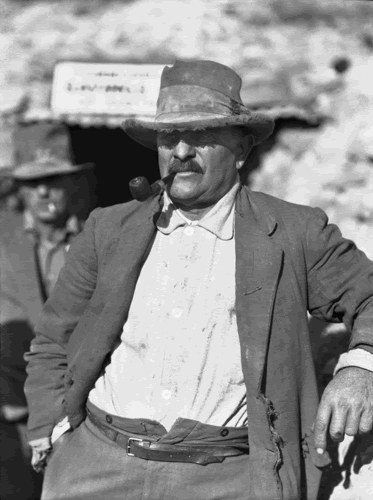

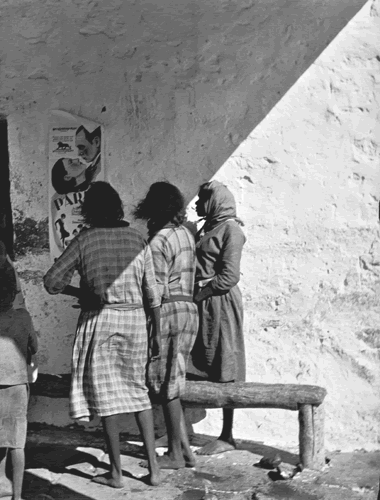

In his photograph of the Woolworth Building in New York of 1926 he uses the only recently rediscovered technique of differential focus with a perspective control camera to imitate the vertiginous impression of looking at such a massive skyscraper from below. He seems to have been well in advance of leading exponents of the documentary idiom such as the Americans Charles Sheeler and Walker Evans, and his pictures may even have influenced the Precisionist painting of the era. But what is especially striking is Hoppé’s humanist approach to the people of the societies he photographed. There is much emphasis on the city and the factory, as well as on the monumental landscapes in his American photography. He sees America as a sort of machine in which people had to perform allotted roles, but at the same time he places them in their context and individualises them wherever possible to show their essential humanity. By the time he gets to Australia in 1930 to undertake his second survey, the human dimension is more marked, and he focuses much more on the everyday life of Australians – including the relationship of Aboriginals to their white “masters”. Although he was not immune to the typological temptations of modernist photography (he was rather too fond of the “noble savage” depictions of Aboriginal hunters, perhaps), Hoppé’s portraits of individuals are softer and more revealing of social distinctions than his American portfolio, and more obviously concerned with the fleeting and the everyday.

Though Hoppé lived until 1972 his reputation waned significantly in the postwar period. In 1945 he sold almost all of his work to a picture library in London. Filed with millions of other pictures under diverse subjects and categories, the identity of the photographer was effectively buried. It was not until the resurgence of photography itself as a cultural medium in the mid-1990s that the value of reuniting this work was realised. His influence stayed alive, however, in the work of those who came after.

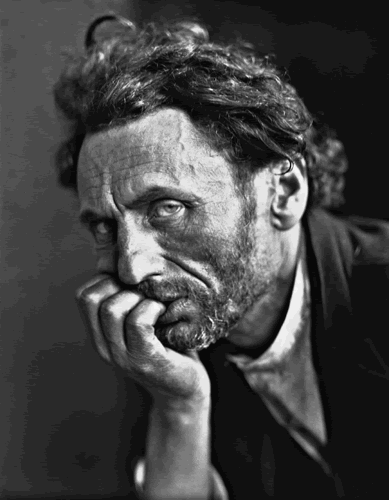

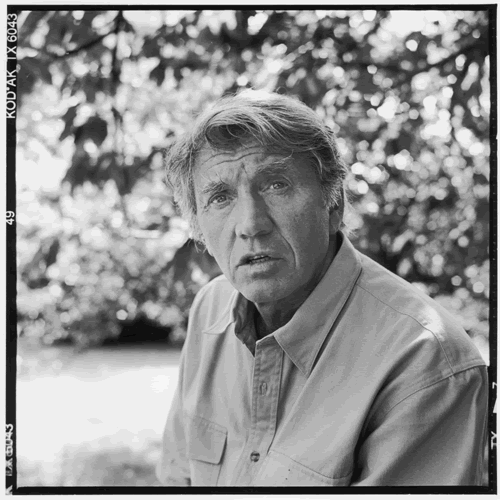

Hoppé’s influence resonates in Don McCullin’s new book, In England. While Hoppé was a child of privilege, McCullin grew up on the mean streets of North London, an upbringing he has described as being in “total ignorance, poverty and bigotry”. While the dapper cosmopolitan made his name in the studio, shooting society wives and ballet dancers, McCullin is best known as one of the world’s outstanding war photographers. Yet both display an intense concern with social relations, with the ordinary and unremarked, with what Henri Cartier-Bresson, the great poet of the moment, said was the true subject of photography: “mankind: man and his life, so brief, so frail, so threatened”. Opposite the title page of In England is McCullin’s iconic portrait of a London teenage gang, the Guv’ners, whom McCullin had known from the Finsbury Park area of London where he grew up. This picture was McCullin’s ticket out, his lucky break. One of the gang was involved in a murder, so through this shot he came to the notice of the Observer. Ever since, he has been known as a backstreet kid made good, an autodictat, a natural. But though worn lightly, McCullin’s profound photographic culture is obvious in every shot. Some years ago he told me how, as a young photographer, he acquired a set of Photogram annuals covering the period from the 1880s to the 1920s, which reproduced the best work of major figures like Stieglitz, Steichen, Evans, Coburn – and, of course, Hoppé. “I paid £10 for them which, in 1966, was two-thirds of my weekly wage, but I told myself this was the cheapest education you’ll get. After the children were bathed and put to bed, while my wife was sewing, I’d spend my evenings going through these books, putting leaves in the pages. Those books became my university.”

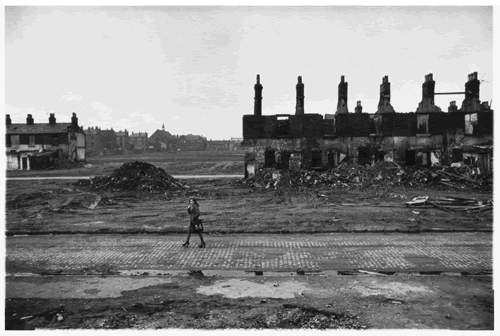

From these models, and his rough upbringing, McCullin carried into his war photography the urge to capture and communicate human suffering. Cartier-Bresson once compared his photographs to the dark paintings of Goya, and McCullin himself keeps an epigram from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (a title he used for one of his own collections) close: “To make you hear, to make you feel, to make you see.” After a long career recording the devastation of war and famine from Vietnam to Beirut, McCullin has turned his attention closer to home. His new book features more than five decades of photographs of his native land, from the cold and gloomy beauty of the Somerset landscapes, where he has lived for the last 20-odd years, to bleaker landscapes of urban desolation and despair.

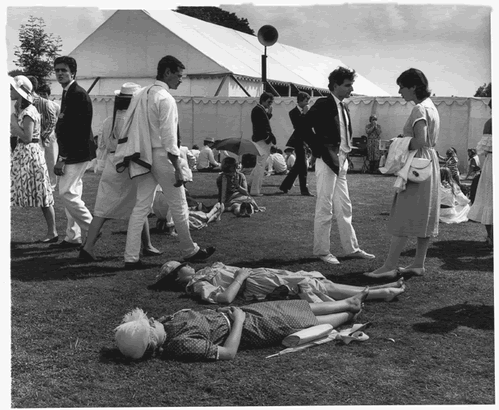

McCullin is best known as a war photographer, but he is also a great documenter of another form of conflict – between rich and poor. He knows both poverty and privilege well and writes in the introduction that “the one can be as crippling as the other”. These photographs of an England that he loves, and fears for, take us from the luxurious pastimes of the wealthy to the harrowing poverty of the dispossessed. They also suggest the undercurrents which link the poverty and destruction of postwar England with the inequality, obesity and new forms of social aggression characteristic of contemporary England. It is a savage vision in some ways, and darkly drawn in McCullin’s sombre palette of greys, but one that also demonstrates a deep compassion.

This is what shines out of the portrait of an elderly couple in Bradford in the early 1970s, a place to which McCullin kept returning because, as he says in his introduction, he found the people so astonishing, so charming. The couple sit in a café, whose meals, you can just make out from the blurred menu in the background, are cheap. This is definitively the pre-Lavazza era. He, most probably a retired miner, has a flat cap and a Players Navy Cut just lit; she wears one of those chiffon headscarves that would have been de rigueur at the time wound over her wispy hair. Their glass cups contain a strong brew, their bowls half-consumed custard. The table is ornamented with a squeezy tomato sauce dispenser and a Tetley’s ashtray. It is the sort of photograph that a post-modern art photographer such as Martin Parr would present ironically – and through a sideways glance. But for McCullin these people are in direct contact with him, and with us through him, acquiescent perhaps in their poverty but still possessing a vestige of pride. He looks directly into the camera with a firm stare, she smiles wanly. They both, of course, are looking at us from an England that has vanished in one sense, but remains beneath the surface.

Speaking of how he developed his craft McMullin says “I became quicker. If I saw something I pounced.” EO Hoppé called it “elasticity”, the ability to get in the right position and the right time, in the right light, to catch the fleeting moment. And as these volumes demonstrate, that is what both photographers achieve magnificently.

In England by Don McCullin was published by Jonathan Cape in 2007. E.O. Hoppé’s Australia and E.O. Hoppé’s Amerika, the first two in a four part series of Hoppé’s lost photographs, were published by Norton in 2007.