It’s been calculated that a three-year-old human infant has a capacity for empathy several factors greater than an adult chimpanzee. In other words, human infants can project their consciousness to seven degrees of separation. What that means is that they can imagine what it’s like to be someone or, significantly, something else at up to seven removes from themselves. There are clearly sound evolutionary reasons for this, even though I’m as wary of according to evolution a pro-active if unconscious role in determining our lives as I am of attributing any kind of conscious or unconscious determination to God.

As we emerged, in fits and starts, into the hunting-pack animals we basically are, it was to our advantage to utilise empathy, along with language, which, as with consciousness, is maybe a consequence of empathy or its source. Just as a limpet has adapted to meet all the requirements necessary to function as a limpet, so we developed this capacity for imagination, the better to second-guess all the contingencies that might befall us, for purposes of survival, planning, organisation, communal living, social cohesion and all the other threads in the infinitely complex tapestry of being both alive and human.

As we emerged, in fits and starts, into the hunting-pack animals we basically are, it was to our advantage to utilise empathy, along with language, which, as with consciousness, is maybe a consequence of empathy or its source. Just as a limpet has adapted to meet all the requirements necessary to function as a limpet, so we developed this capacity for imagination, the better to second-guess all the contingencies that might befall us, for purposes of survival, planning, organisation, communal living, social cohesion and all the other threads in the infinitely complex tapestry of being both alive and human.

Our species of hominid has been around for a comparatively short time, so there’s every good reason to assume – unless you happen to be a creationist – that the hominids we evolved from, as well as those that branched off from our common ancestors in other, ultimately less enduring, directions, possessed this capacity too, to a lesser or maybe even a greater extent. The point, however, lies in the consequences of us developing empathy to the degree we have.

I’ve believed for a long time that as a species we are perfectly adapted to optimal living in the African plains hundreds of thousands of years ago, whispering to each other in our Ur-language as we manoeuvre round whatever representative of Pleistocenic megafauna our little pack of Homo Sapiens are trying to entrap so we can eat it in order to survive, constantly second-guessing its next possible move by imagining what we’d do in its circumstances. In most other regards, however, we’re hopeless.

Compared only to other animals, we’re so stupid that we can’t fly without building incredibly complicated and disastrously filthy machines; we can’t breathe underwater, or use echo location, or even maintain our body temperatures at comfortable or even survivable levels in most of the world’s latitudes, without doing the same. We are good at running and jumping, for a few years of our lives at any rate, and talking and laughing and having sex, but otherwise we have to go to school for years and years in order to be taught all the other things we now need simply in order to survive, because we’re too stupid to work it out for ourselves. Even then, we’re too stupid to work out the consequences of most of our actions. If you wanted to take the long view and get all Gaiaist about this, you might choose to see the whole history of human civilization as one long, unwittingly scrawled suicide note for our entire species, and all its achievements and failures, its triumphs and tragedies and atrocities as the accidental consequences of us growing brains overburdened with consciousness and empathy, which, purely as a by-product of that adaptation, allowed us to devise ways of reaching far beyond the defining circumstances that led to the initial adaptation. Sticking with Gaia, you might also choose to view the charivari of natural disasters we ceaselessly endure and which, so far, we’ve survived, as Gaia doing her very best to shrug us off, like a nasty cold.

But let’s not get too judgmental quite yet. Nor should we indulge too deeply in ideas of super-consciousnesses, however well-intentioned or metaphorical their invocation. Instead, let’s stay with empathy.

As an innate, hard-wired evolutionary survival tool, empathy allows human beings to project their own individual consciousness in all directions, which we do constantly and incontinently because we can’t do anything else. It allows us to love other human beings, and to hate them, but more importantly to imagine what it’s like for them to be loved or hated, and what it’s like for them to love or hate us. From our capacity to imagine what it’s like to be someone else also spring pity, compassion, generosity, envy, jealousy, covetousness, revenge, hope and remorse. I’d suggest it’s also what moulds the intensity of almost all of our other human emotions.

It also made it possible for us to view the world around us, project ourselves into it and beyond the horizon and then report back so we can reflect on the position and condition we find ourselves in and act accordingly. This isn’t either a spiritual or a physical extension of ourselves beyond ourselves, but the result of our capacity for imagination; it’s not anything “paranormal” like thought-transference or telepathy, although that’s what it actually is, but it is innate and of ourselves. Just like the Bishop of Southwark, it’s what we do, because we’re human.

A further consequence of this is the way it allows us to attempt to make sense of our world by using methods to control it, both individually and collectively. For this we can thank our enhanced empathetic capacity to build imaginatively on memories of the past and thus imagine possible futures. We sought to control the world in other ways, consequent upon our capacity for language and our opposable thumbs and forefingers. We sought to control the experiences of our lives by retelling them, filtering them through our individual consciousness and thus recreating them; and, by talking about ourselves, language found its true human metier, not simply as a medium of instruction, but through high and low gossip, the real songlines with which we mapped the world around us. We filtered and sought to control the world in other ways too, by recreating it in paintings daubed on cave walls, and we’ve continued to do so ever since, either representationally or imaginatively, in every genre all the way up to political cartoons. Hence, in a nutshell, art and literature, and also music, through which we recreate and echo the rhythms of our world and our lives.

Thereafter we operated on a more interventionist level: we grabbed each passing contingency, and along the way developed agriculture, which led to permanent settlements, notions of property, wars to dispute that property, kings to fight those wars, capitalism to fund the kings, different politics to counter the capitalism, and on it goes. And another aspect of the desire for control is the urge to understand: hence inquiry, philosophy, science, politics and economics and also, of course, religion. I believe that these are all accidental by-products of our capacity for empathy, but most important of all, all have their source within us as human beings and nowhere else.

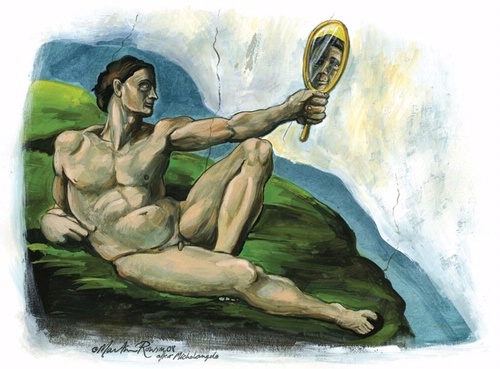

So, thanks to empathy we project our individual consciousnesses into everything around us, which then, like a million million mirrors, bounces back the projection and reflects us back to ourselves. But they don’t just reflect: in our perception of them, we imagine they absorb something of us too. That’s why, probably uniquely of all the animal species that have ever lived, we keep pets. It’s because we imbue them with our own qualities, which then reflect back on us and to our own advantage, and thus make us feel better. After all, the appearance of requited or reciprocated love, however inarticulate, is just as capable as the real thing of unleashing all those lovely endorphins, the hormones our bodies release to make us feel good. And it’s not only pets. It’s toys, teddy bears, dolls, knick-knacks and geegaws, a favourite chair or a precious souvenir, even bits of soggy old blanket we hug and suck to destruction for comfort. We imbue all of them with levels of importance to us that they hardly merit objectively, and although this is, in many ways, motivated by the same things that draw a dog to its bone, its intensity and scope are, albeit quantitatively, uniquely human.

For precisely the same reason, and in exactly the same way, the same goes for God too.

This is an edited extract from Martin Rowson's latest book, The Dog Allusion, published in March by Vintage.