“High heels are to us what corsets were to late Victorian women. They are inhumanly uncomfortable – and yet self-imposed,” observed Sarah Sands recently in the Independent on Sunday, before confessing that she is saving up for “some perilously high purple suede shoes by Christian Louboutin.”

And she won’t be alone. Because this is the season of statement footwear: extravagant, fantastical, eccentric and, above all, high, high, high. Balenciaga’s most coveted summer accessory is a pair of multi-stranded gladiator boots, leather-laced up to the knee and balanced on unfeasibly steep wedges. Prada offer gnarled heels ending with erotically charged knobs in contrasting colours. Marc Jacobs has come up with an inverted construction which gives the shoe height with the illusion of no heel at all.

And she won’t be alone. Because this is the season of statement footwear: extravagant, fantastical, eccentric and, above all, high, high, high. Balenciaga’s most coveted summer accessory is a pair of multi-stranded gladiator boots, leather-laced up to the knee and balanced on unfeasibly steep wedges. Prada offer gnarled heels ending with erotically charged knobs in contrasting colours. Marc Jacobs has come up with an inverted construction which gives the shoe height with the illusion of no heel at all.

And all the signs are that heels are going even higher. Antonio Beradi’s Terminator sandals, at 14cm, have sold out already. Christian Louboutin’s black ponyskins, created for Roland Mouret, teeter up to 16cm, while Louis Vuitton’s statement for next autumn is a court shoe with a 17cm heel.

These ludicrously exaggerated creations may be destined for the brave, the foolish, for the catwalk, or for the so massively rich that they don’t ever have to do anything as vulgar as walking. But that doesn’t make the rest of us immune to their killer charms. So how can any self-respecting rationalist possibly allow herself to fall prey to a fashion item that is so manifestly painful, disfiguring and impractical?

Sands is baffled that so many feminists like herself are still in thrall to high heels. “It is interesting that high heels have survived feminism and the tracksuit … Women burned their bras but now subject their feet to terrifying pieces of engineering in order to lengthen their legs and reduce their waists.”

But not all feminists display the same weakness. Indeed, the high heel has been a central battleground of sexual politics ever since the emergence of the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. Many second-wave feminists rejected what they regarded as constricting standards of female beauty, created by men for the subordination and objectifying of women. “In 1973 I gave up beauty practices as part of that movement, supported by the strength of the thousands of heterosexual and lesbian women around me who were also rejecting them,” declared the radical feminist Sheila Jeffreys in Beauty and Misogyny. “I stopped dyeing my hair ‘mid-golden sable’ and cut it short. I stopped wearing make-up. I stopped wearing high heels and, eventually, gave up skirts. I stopped shaving my armpits and legs.”

For many of us, though, such sacrifices were just too extreme. I was out there with the rest of the gang demanding equal pay and a woman’s right to choose. I could recite the seven demands of the movement with aplomb and was even capable of a healthy snarl when a man had the temerity to open a door for me. But give up lipstick, shaved armpits and, above all, gorgeous shoes? Never. I can even remember going on a Reclaim the Night march in my utterly impractical but fabulous cork-wedged gold sandals. I ended up falling into a lamp-post and being helped by a kind policeman who probably would have whacked me one with his truncheon had I not looked so helpless.

And that’s why, in the radical feminist lexicon, wearing high heels has to stand out as the most pointed betrayal of all. They demean, they constrain, they deform, they inhibit. And they’re downright dangerous. Most deadly of all is the stiletto, the killer heel. It can lead to bunions, back problems and disfigured toes. Deformities resulting from years of wearing them can be as severe as the foot problems that used to be seen in Chinese women whose feet had been bound – a tradition which persisted until it was outlawed in 1911.

It’s no coincidence that Cinderella, the most ubiquitous of fairy tales, originated in ninth-century China, where the tiny foot has long been considered the exemplar of female grace and beauty. We still squeeze our feet into unwieldy shapes, inject them so that they won’t be such agony when we hobble and totter, even have surgery to taper and refine them, all in the quest for a slim, tiny, perfect foot. Women are just so many Ugly Sisters, cutting off toes and heels in order to slip the daintiest of feet into that elusive glass slipper.

But although high heels can cripple and damage and harm us, they can also be empowering. You can’t run away from an attacker in them. But they make a convenient deadly weapon. They give the impression that a woman is helpless and vulnerable. But the four or five inches of stiletto cancel out the average difference in height between the sexes, bestowing a shoulder-to-shoulder equality. Those extra inches also denote money and status.

One of the most curious early examples of women’s attempts to gain height through their shoes is the chopine, most commonly worn in Venice in the early 14th century. Thought to have originated in the East, the chopine was a raised wooden platform on which the shoe could rest. It had a vaguely practical intent – to protect the wearer from the mud and filth of the medieval street – but soared way beyond anything that could be seen as useful. Chopines could be as high as 20 centimetres, so high that it was impossible to walk in them unaided. You would either have to hobble around on sticks or lean on your servants.

One of the most curious early examples of women’s attempts to gain height through their shoes is the chopine, most commonly worn in Venice in the early 14th century. Thought to have originated in the East, the chopine was a raised wooden platform on which the shoe could rest. It had a vaguely practical intent – to protect the wearer from the mud and filth of the medieval street – but soared way beyond anything that could be seen as useful. Chopines could be as high as 20 centimetres, so high that it was impossible to walk in them unaided. You would either have to hobble around on sticks or lean on your servants.

That was one reason why the chopine was confined to upper-class women who could afford to rest on the shoulders of others. Another was that height conferred status – the taller you were the more superior in class and wealth. Interestingly, though, the chopine was also worn in Venice by courtesans, probably so that they could be visible above the teeming crowds. Indeed, many of our most cumbersome and damaging fashions emerged from the bordello. Footbinding itself is thought to have derived from Chinese court dancers, who would also serve as prostitutes.

So high heels are commonly associated with both the aristocracy and the brothel. And shoes and heels in general are an acute barometer of cultural and social norms, going up and down, high and flat, in accordance with the mores and the political climate of the age. The high heel as we might recognise it was introduced into the French court in 1533, the year that Catherine de Medicis, aged 15, brought a pair with her from Florence when she married the Duke d’Orleans. They were eagerly embraced by Parisian noblewomen and the fad spread across Europe. Marie Antoinette went to the guillotine in high heels and became the symbol of all the lavish decadence of the aristocracy.

So when the French monarchy fell, so did the height of shoes. Elaborate clothing and fancy heels were discarded in favour of simple, flowing garments and flat pumps, following Rousseau’s notions of the benefits of the natural order. This was the era when men and women’s appearances dramatically diverged. Men replaced flamboyant dress with the sombre garb of rationality while women’s more decorative attire was seen as evidence of their innate irrationality.

Men have never returned to high heels, whether the manly ones traditionally favoured by Cossack horsemen or Prussian fighters, Louis XIV’s signature red heels or the fanciful footwear of 18th-century London dandies. But women’s heels rose again in the Victorian era, when high-heeled laced-up boots would be worn under the crinoline and the bustle – just an alluring pointed toe visible under the swathes of skirt and petticoats. At a time when demands for female enfranchisement were growing, these lavish fashions, reminiscent of 18th-century excess, helped to reinforce the idea that women were essentially too frivolous to participate in public life.

At the same time, women’s elaborate costumes were a vehicle for men to display their success and economic status. But once again, clothing that conveyed social privilege also implied sexual impropriety, according to the fashion historian Elizabeth Semmelhack. In her article “A Delicate Balance: Women, Power and High Heels” she explains that in the 19th century “the presence and the idea of the courtesan and sexual commodification became central to European intellectual and aristocratic thought. The concept of the courtesan linked female ‘power’ and sexual manipulation. … High heels in particular became infused with erotic significance.”

Then, in reaction to the seeming prudery and constraints of the Victorians, came the Roaring Twenties and the flappers. Chests flattened, skirts shortened, heels became more boyish. But after the Second World War fashion became demure and ladylike once again as women who had been active during the war were now encouraged to return to the home and to take on their traditional wifely role. In keeping with the return to femininity, Christian Dior launched his New Look, emphasising cinched waists and full skirts. And its ideal accompaniment, perfected by Dior’s favourite shoe designer Roger Vivier, was the stiletto heel. So wedded did many women become to the allure of the high heel that they would wear stilettos all day – even at home, doing household chores. But at the same time as signifying ladylike elegance, high heels were, as ever, associated with the whorehouse. “By the mid-1950s,” writes Semmelhack, “cultural icons of femininity and sexuality, whether they were Vogue models, television housewives or Hollywood bombshells, were typically represented in stilettos.”

All of that changed with the advent of the Swinging Sixties, which, echoing the look of the Twenties, were characterised by miniskirts, bobs and boyishness – a reaction to the buttoned-up, prim and coiffed era that had never had it so good. The liberation movements of the late ’60s were also coloured by a rejection of the artificial and the commercial in favour of natural, let-it-all-hang-out freedom from constraint, combined with anti-establishment revolutionary politics. For some, women’s liberation meant not only liberation from patriarchy but also from capitalism. Rejecting the traditional trappings of femininity was often seen as an escape from both.

Flat, comfortable shoes have always been associated with the working class – with people who have to work and have to walk; high, impractical ones with the leisured classes. So eschewing high heels was also an expression of solidarity with working people. But the declared socialism of radical feminism was by no means shared by all the sisters. Some may have opted out of any dealings with the military/industrial complex that was spawned by the devil of patriarchy. Many others, though, wanted a share of the action.

Flat, comfortable shoes have always been associated with the working class – with people who have to work and have to walk; high, impractical ones with the leisured classes. So eschewing high heels was also an expression of solidarity with working people. But the declared socialism of radical feminism was by no means shared by all the sisters. Some may have opted out of any dealings with the military/industrial complex that was spawned by the devil of patriarchy. Many others, though, wanted a share of the action.

And that was how power dressing, big shoulders and serious heels came to dominate the ’80s – the era of glass-ceiling shattering when women started to enter the boardroom and aim for the high stakes. The clickety-clack of stilettos on hard surfaces came to mean the approaching of the boss rather than the secretary, the wielder of whips as well as the shackled whore.

But even the proudest and most powerful high heel was still, as ever, linked to sex. By the turn of the 21st century, the association became more overt and aggressive as classic courts were replaced with footwear reminiscent of streetwalkers and dominatrices. So the stiletto continues to persist as one of the fundamental accoutrements of sado-masochistic and fetish sex, along with the statutory suspenders and black stockings, bustier and handcuffs. Far from regarding it as an aberration, the sexologist Havelock Ellis saw foot fetishism as quite normal because “the human species prefers itself a little bent out of natural shape.”

And that is what the high heel is able to achieve. It tapers the toes, arches the instep, lifts the calves and alters the posture so that buttocks are raised and breasts thrust forward. High heels create the illusion of longer and more defined legs, hinting upwards to the centrifugal point of sexual action. And high heels demand a mincing, swaying walk quite markedly different from the confident stride of a man. Marilyn Monroe was reputed to have one heel made a quarter of an inch shorter than the other to aid her characteristic wiggle.

In The Sex Life of the Foot and Shoe, William Rossi claims that men derive a variety of pleasures from observing the sashaying buttocks and undulating hips of the high-heel walk. The “erotic magic” of high heels feminises the gait in a way that makes women appear helpless, so appealing to men’s instincts of chivalry while at the same time resembling the position of the foot during orgasm. But he warns there’s a darker side to such stimulation. “Not a few men are sexually aroused to erection by observing women walk with obvious distress in tight shoes. One man confessed: ‘Even when I hear a woman say her tight shoes are killing her – that’s enough to bring an instant erection.’”

Sheila Jeffreys cites Rossi and other fetish experts to reinforce her own argument that men love to see women in high heels not despite their pain and discomfort but because of it. They desire to hurt and denigrate us. What she ignores, though, is the prevalence among shoe fetishists of a preference for masochism. Freud, after all, regarded fetishism as a male response to anxiety about the sexual act. So for him the foot was a natural object of fetish, neutralising men’s fear of castration by creating an erogenous substitute for genitalia. In his iconography, the shoe is the vulva and the foot the phallus which could enter and inhabit it, the fetishism a strategy for coping with male vulnerability. Fetish literature abounds with accounts of men being flayed by women, impaled by their spiked shoes, punished and trampled and strangled. The sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing believed that all fetishists were masochists, as did Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, author of the ultimate paean to sado-masochism, Venus in Furs. His heroine, the original dominatrix, humiliates, taunts and thrashes the helpless lover lying at her feet and begging for punishment as he licks her shoes.

And you don’t have to be a whip-wielding dominatrix or a dagger-heeled lap-dancer to recognise the surge of power and pleasure that comes from a killer stiletto. It can even be good for you. High heels help to strengthen legs and pelvic muscles, according to new research by Dr Maria Cerruto, from the University of Verona. Her study of 66 women under the age of 50 found that even a moderate heel relaxed electrical activity in the pelvic area by up to 15 per cent, leading to greater stamina and better sex. No wonder so many women find that wearing high heels makes them feel liberated.

“We do it for the image in the mirror, the reflection of ourselves as hot and in charge,” writes Nancy Friday in The Power of Beauty. She describes the sensation as a declaration of independence, “an extraordinarily satisfying goal that we can live with more happily than with a man; who needs him?” And aping familiar stereotypes can be a strategy for undermining them, according to Judith Butler, who views gender as a social construct, a series of blueprints ripe for challenging and discarding.

In Adorned in Dreams, Elizabeth Wilson even makes the case for the positive benefits of fetishism. “To the extent that fetish fashion is popular with women, in large part this is because it adds the idea of power to femininity. Another word for power is freedom. … What Vogue calls the ‘strong and sexy’ look has become the paradigm of contemporary fashion. This is a direct result of women’s liberation.”

For hardliners like Jeffreys, such commentators are mere apologists for the status quo, traducing the fundamental tenet of feminism by separating the personal from the political. But by concentrating on the male gaze she dismisses the experiences and preferences of women themselves. If we claim to enjoy our shoes, she snorts, we are merely consenting to our own slavery.

This uncompromising stance simply doesn’t acknowledge the possibility of irony. When the designer Vivienne Westwood clothes us in pointed bras, tight-laced bodices and platform shoes so high that Naomi Campbell stumbled off the catwalk in them, she may regard her creations as playful comment. For radical feminism they’re another submission to the patriarchal enemy, as are the self-consciously fanciful excursions of John Galliano, the blatant sexuality of Tom Ford, Dolce & Gabbana’s parodic spike-heeled sandals emblazoned with the word “SEX” in rhinestones.

This uncompromising stance simply doesn’t acknowledge the possibility of irony. When the designer Vivienne Westwood clothes us in pointed bras, tight-laced bodices and platform shoes so high that Naomi Campbell stumbled off the catwalk in them, she may regard her creations as playful comment. For radical feminism they’re another submission to the patriarchal enemy, as are the self-consciously fanciful excursions of John Galliano, the blatant sexuality of Tom Ford, Dolce & Gabbana’s parodic spike-heeled sandals emblazoned with the word “SEX” in rhinestones.

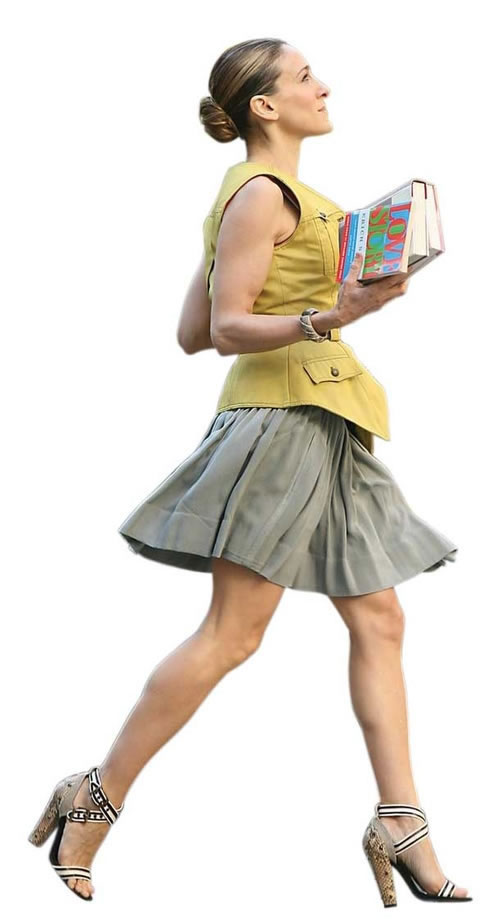

In such a stern philosophy there’s not a lot of room for fun. And yet most women who love shoes enjoy above all the license that they give us to play. And that is the leitmotif of the television show that raised the status of crazy shoes to that of cultural icon. Packed full of parody and irony, self-criticism, doubt and affirmation, Sex and the City celebrates women’s strengths but also their foibles. It turned designer Manolo Blahnik into a global celebrity but frequently ridicules Carrie’s obsession with his shoes, epitomised in the episode when she begs a mugger to take her purse and her watch but to leave her beloved Manolos. Her addiction is portrayed as a soppy but delicious love affair.

Everyone who has fallen prey to beautiful shoes knows that the appeal is a kind of seduction – flirty, funny, frivolous, dangerous yet irresistible. Blahnik himself sees his shoes that way. “Toe cleavage is very important as it gives sexuality to the shoes,” he writes. “But careful you only show the first two cracks, you don’t want to give too much away, you’re not that type of girl. … As for the heel, honey, it’s got to be high. The transformation is INSTANT. It’s the coup de théatre.”

Now that the film version of Sex and the City is about to be released, we’ll be treated to even more fantastical, absurd outfits, reminding us that it’s possible to be both foolish and wise, independent yet vulnerable. Sarah Jessica Parker, who plays Carrie, understands exactly the interplay between true love and banter, strong womanhood and silly vanity. Wearing Blahniks, she says, takes time and trouble. You have to learn how to wear his shoes. “It doesn’t happen overnight ... I’ve destroyed my feet completely, but I don’t care. What do you really need your feet for, anyway?”