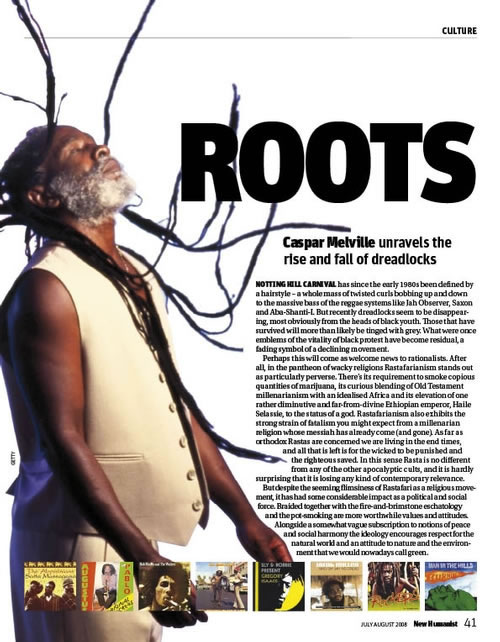

Notting Hill Carnival has since the early 1980s been defined by a hairstyle - a whole mass of twisted curls bobbing up and down to the massive bass of the reggae systems like Jah Observer, Saxon and Aba-Shanti-I. But recently dreadlocks seem to be disappearing, most obviously from the heads of black youth. Those that have survived will more than likely be tinged with grey. What were once emblems of the vitality of black protest have become residual, a fading symbol of a declining movement.

Perhaps this will come as welcome news to rationalists. After all, in the pantheon of wacky religions Rastafarianism stands out as particularly perverse. There's its requirement to smoke copious quantities of marijuana, its curious blending of Old Testament millenarianism with an idealised Africa and its elevation of one rather diminutive and far-from-divine Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie, to the status of a god. Rastafarianism also exhibits the strong strain of fatalism you might expect from a millenarian religion whose messiah has already come (and gone). As far as orthodox Rastas are concerned we are living in the end times, and all that is left is for the wicked to be punished and the righteous saved. In this sense Rasta is no different from any of the other apocalyptic cults, and it is hardly surprising that it is losing any kind of contemporary relevance.

Perhaps this will come as welcome news to rationalists. After all, in the pantheon of wacky religions Rastafarianism stands out as particularly perverse. There's its requirement to smoke copious quantities of marijuana, its curious blending of Old Testament millenarianism with an idealised Africa and its elevation of one rather diminutive and far-from-divine Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie, to the status of a god. Rastafarianism also exhibits the strong strain of fatalism you might expect from a millenarian religion whose messiah has already come (and gone). As far as orthodox Rastas are concerned we are living in the end times, and all that is left is for the wicked to be punished and the righteous saved. In this sense Rasta is no different from any of the other apocalyptic cults, and it is hardly surprising that it is losing any kind of contemporary relevance.

But despite the seeming flimsiness of Rastafari as a religious movement, it has had some considerable impact as a political and social force. Braided together with the fire-and-brimstone eschatology and the pot-smoking are more worthwhile values and attitudes. Alongside a somewhat vague subscription to notions of peace and social harmony the ideology encourages respect for the natural world and an attitude to nature and the environment that we would nowadays call green.

But, far more effectively, it was also a vehicle for social change. In his essay "Black Hair/Style Politics", the cultural critic Kobena Mercer notes that dreadlocks, together with the Afro, mark a decisive political moment. This "epistemological rupture" was when black hair, "historically devalued as the most visible stigmata of blackness second only to human skin", was reclaimed as a symbol of pride. A racial characteristic that had until then been derided as "nappy" or "frizzy" or simply "bad" was suddenly transformed into a sign of vitality and of beauty.

So while nearly all Rastafarians have dreadlocks, many other people have adopted the style as a statement of black pride and politcal rebellion. The dreadlocked sociologist Paul Gilroy, who has written widely on the politics of race, argues that these politcal and social meanings were woven into Rastafari from the very beginning. What drew him to dreads was not Jah, or the dream of an African idyll, but the anti-colonial politics it articulated:

"Rastafari began in Jamaica, an island nation born in and forever scarred by slavery and colonialism," he told me. "There were two key moments in its development. First, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in 1935. Those images of tanks and Mustard Gas used against Africans armed only with spears awoke a new kind of international awareness in the Caribbean, a sense of common cause with Africa, and an understanding of the link between slavery and 20th-century colonialism. Then in 1937/8 there was huge labour unrest in Jamaica; it looked like it might turn into a full-scale rebellion. These two incidents provided a way to link slavery and colonial oppression aboard, with economic and social conditions at home. The Rastafarian movement pulled these threads together using a King James Bible inspired morality, in which slaves and their descendents - the 'sufferers' - became the chosen people and Ethiopia the promised land." The movement was named for the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie - before he was crowned he was Ras, Prince, Tafari - who was taken as the embodiment of God: Jah. In this model the forces of colonialism and exploitation - including the Jamaican government, were perceived as evil-doers: "Babylon".

In Rasta ideology naturalness was counterposed to artificiality and modernity. "This orientation to the natural world, the Rasta 'livity', leads them to look on themselves as custodians of the earth," Gilroy explains. "No one needs to give a Rasta lessons in conservation or the environment. In fact they have lessons to teach." Central to this livity is the Nazarite injunction against cutting the hair, based on Leviticus 21:5: "They shall not make baldness upon their head." The resulting dreadlocks also linked Rastas symbolically with other religious outsiders like the Sadhus of India.

In Rasta ideology naturalness was counterposed to artificiality and modernity. "This orientation to the natural world, the Rasta 'livity', leads them to look on themselves as custodians of the earth," Gilroy explains. "No one needs to give a Rasta lessons in conservation or the environment. In fact they have lessons to teach." Central to this livity is the Nazarite injunction against cutting the hair, based on Leviticus 21:5: "They shall not make baldness upon their head." The resulting dreadlocks also linked Rastas symbolically with other religious outsiders like the Sadhus of India.

The rise of the popularity of dreadlocks, despite their being shorn of any attachment to a particular religion, tells the story of Britain's racial politics of the '70s and '80s. In the early years in Jamaica Rastafarians tended to live like a religious sect, in communal housing in the Kingston ghetto, where the poor and often homeless children were cared for, and in model Rasta communities in the Jamaican hills like the remote Pinnacle settlement founded by Rasta prophet Leonard Howell. Haile Selassie's visit to Jamaica in 1966 opened up a new phase for Rasta, as the movement gained publicity and momentum - it began to go what, using the dread syntax, we could call "outernational", and started to become as much a political statement as a religious one. "I remember seeing images of the Mau Mau [Kenyan rebels fighting for independence]," Gilroy recalls, "and they had dreadlocks." There were a variety of motives - "both sacred and profane" - drawing people towards Rasta livity and locks.

For Lola Young, the writer and cultural critic who as Baroness Young of Hornsey is one of two dreadlocked peers in the House of Lords, for example, the decision was purely practical. She wanted a low-maintenance hairstyle. "For me there was no attraction in any kind of religion. The idea that Rasta was connected to a mythic African naturalness is of course a kind of ideology, and I found Rasta's patriarchal structure very off-putting." In fact some of the most negative comments she received once she grew locks were from male Rastas who wanted to insist that she covered her hair in public. So why associate yourself with a religion? The answer, for Young, lies in the politics of style, and the way in which dreads challenged prejudices - not only those of white people and Rastafarians themselves, but also those of her family: "My sister, who lived in Lagos, was very shocked. But I like challenging preconceptions."

Though growing in Jamaica since the 1930s Rasta did not arrive in Britain in any visible way until long after the majority of the West Indians had come to settle in Britain. No one on the SS Empire Windrush had dreadlocks; they were smartly dressed in their finest city clothes and their hair was tightly cropped. For these respectable British citizens dreadlocks were associated with the poor and the unemployed in Kingston, and with the backwards folks in the hills. Yet it was when they arrived in Britain that this generation of British West Indians discovered that they were, after all, black - the place prepared for them by the ideology of white supremacy. In the slow dawning of this grew a new sensibility which looked on locks differently.

Bob Marley's are the most globally recognised dreadlocks, and his music has been the most influential vehicle for spreading the Rasta worldview, but in the late '60s he, too, had the shorn hair and tight-fitting suits: he wanted to be Frankie Valli. "When I met Bob Marley in London, around 1970," recalls Gilroy, "he had only just started to grow his." It was when Gilroy was a student in Birmingham in 1977 that he decided to let his hair grow. But it was a decision he did not come to lightly. "I remember going to see David Hinds, of the band Steel Pulse. We spoke for a long time about 'locksing'. He was very aware that dreadlocks had started to be the thing that was always used to market reggae bands, and we thought carefully about that. You were creating problems for yourself in relation to work, to the police and to the general attitudes which associated locks with uncleanliness. You were accepting a kind of pariah status."

The same scene must have been playing out in Birmingham, Manchester and London, as locks sprouted prolifically from the heads of young black men across the country. Was it a case of mass conversion to a religious cult? That's not how Gilroy sees it. "People were saying, 'Well, if I'm going to be secondary then I'm really going to look secondary. If it's going to be assumed that I am dreadful then I'm going to look dreadful.' Literally dread-full."

The same scene must have been playing out in Birmingham, Manchester and London, as locks sprouted prolifically from the heads of young black men across the country. Was it a case of mass conversion to a religious cult? That's not how Gilroy sees it. "People were saying, 'Well, if I'm going to be secondary then I'm really going to look secondary. If it's going to be assumed that I am dreadful then I'm going to look dreadful.' Literally dread-full."

This was also the time of punk, and the relationship between the two was obvious to those who were there. The film-maker and DJ Don Letts made the point in an interview with the punk fanzine Sniffin' Glue in 1977: "The reggae thing and the punk thing ... it's the same fuckin' thing. Our Babylon is your establishment. Like with me hair, and the red, gold, and green. A punk wears his clothes. He's makin' an outward sign he's rebelling." It may all sound like youthful bravado now, but the fact that this was only four years before the violent riots in Bristol, Liverpool and London lends it a certain prescient gravity.

Beyond the symbolic rebellion there was the unique way in which Rasta broadcast its message to a wide audience: reggae music. All the top stars of reggae's golden period of the late '70s - Marley, Burning Spear, Gregory Isaacs, Dennis Brown, Dillinger, Max Romeo - wore dreadlocks and professed allegiance to Rasta. Songs like Bob Marley's "400 Years" and "War" (the latter a transcribed version of a speech Haile Selassie gave to the UN) articulated the Rasta political sensibility. Others, like Burning Spear's "Man in the Hills" or Jacob Miller's "Tenement Yard", talked of life in the Kingston ghetto and the joys to be found retreating to a rural Rasta community. Yet another subgenre broadcast what might be called Rasta humanism: songs which tied together biblical injunctions, folk wisdom and good sense to lay out a charter of socially conscious behaviour: songs like Johnny Osbourne's "Truth and Rights" and Burning Spear's "Social Living".

The Manichean Rasta theology, which projects a world caught between the righteous and Babylon, was frequently symbolised in song as the battle between the dreadlocks and the baldheads. Bob Marley's lyric "I'm gonna chase those crazy baldheads out of town" sums up the Rasta attitude.

For Gilroy these narratives amount to a serious popular engagement with issues of local and global oppression, and in particular a coherent response to corruption and hypocrisy: "It's about the critique of people who are prepared to be complicit made by those who are not."

In 1976 and '77 there were violent disturbances at Notting Hill Carnival. By the turn of the '80s dreadlocks were the most visible sign of black self-determination and resistance. And yet, even then, it was starting to unravel.

Global Rasta Bob Marley died in May 1981, and even before his death he had become an international star and could therefore no longer function as a symbol of a distinctly black cultural and political solidarity. Plenty of other reggae stars kept their locks, and their Rasta allegiance, but throughout the '80s reggae music turned away from the "deeper", more contemplative sound of "rockers" and "roots" toward a more openly confrontational and materialistic "ragga" sound, influenced by American hip hop, that was at odds with Rasta's espousal of peace and disengagement from Babylon.

And then there was the emergence from within the British city of new styles, fashions and identities, new ways of being black and British that were not subservient to either narratives of African return or imported black American models, but cleverly synthesised elements of both. Lola Young identifies the moment at which dread became part of a new "pick 'n' mix" style: "In 1987 Soul II Soul came along, with a whole new sense of black style and fashion and a new hairstyle; the Funki Dred. Here you had short locks on the top of the head, but shaved sides, so it emphasised artifice. The point the Funki Dred seemed to make was you could be black and British and that you could be modern, employable and make money. Some people saw this as a betrayal, others as progress." Rasta spoke for the poor and the sufferers, and offered hope of "redemption" in an imagined promised land. But it had little to say about economic self-determination or social success. After Soul II Soul, who combined hit records with club production and clothing lines, young people began to create their own proudly mixed-up urban identities. Rastafariansim was left behind. Hybridity, not racial unity, was the buzzword as youth style and culture became big business and a viable career path.

Yet a resilient echo of dread remains, in the hairstyles, in the references to classic reggae that continue to pop up in contemporary black music, and in the Rasta worldview. Unsophisticated as the dread division of the world into the righteous and the hypocrite may be, it continues to provide a reminder both of racial history and that this history is not over: "I get some funny looks in the House of Lords chamber," says Baroness Young. "It still makes some people very uncomfortable." "We may have won the battle here," says Paul Gilroy, "but it is yet to be won in other places. If I go to certain parts of Europe people still look at me as if I came in on the sole of someone's shoe. One of the reasons I don't cut my locks is because we still have to challenge these routine assumptions. I still want to carry a certain symbol of my refusal to be complicit in that."

As a religious cult Rastafari has painted itself into a corner, where it waits for judgement day wreathed in clouds of cannabis smoke. It's hardly surprising that for young people in Britain in the 21st century the fatalistic Rasta theology has little purchase on their everyday lives.

Nonetheless, it is surviving in one little patch of London. The head gardener in Russell Square is a dread. In the winter he wears a plastic bag over his locks to keep out the rain. But in summer when he bends to his task in the rose bushes, his locks are free, dangling like the vines of a creeper, blending in with all the green goodness thriving and growing and reaching for the sun.