One of the strangest elements of the recent electioneering in the US, in the eyes of any humanist observer, must be the importance of candidates’ pastors. That Barack Obama’s and John McCain’s priests have become pivotal in arguments around their campaigns seems bizarre and anachronistic. Yet the difference between the ugly racism of John Hagee and Jeremiah Wright’s anti-war, leftist rhetoric (entirely sensible to many outsiders, despite some of his more rabid racist utterances, but hugely controversial in the US context) is marked.

One of the strangest elements of the recent electioneering in the US, in the eyes of any humanist observer, must be the importance of candidates’ pastors. That Barack Obama’s and John McCain’s priests have become pivotal in arguments around their campaigns seems bizarre and anachronistic. Yet the difference between the ugly racism of John Hagee and Jeremiah Wright’s anti-war, leftist rhetoric (entirely sensible to many outsiders, despite some of his more rabid racist utterances, but hugely controversial in the US context) is marked.

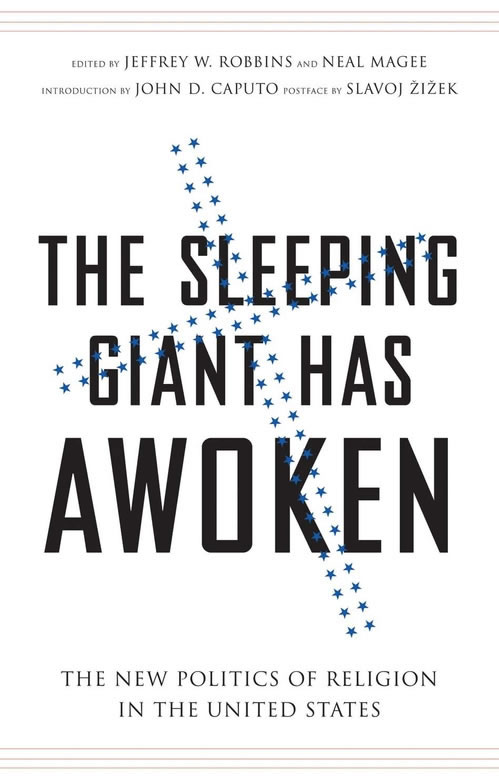

So maybe American political religiosity isn’t entirely a right-wing one-way street. However, recently the emphasis has unsurprisingly been on the astronomical rise of a Religious Right that combines nationalism and free-market fundamentalism with the crusading intensity of the evangelical movement. The Sleeping Giant Has Awoken, edited by Jeffrey W Robbins and Neal Magee, tries to negotiate the dialectical tensions between these two elements – the possibility of a left-leaning “spiritual” politics informed by Christianity actually opposing the worrying trends in the country, and the reality of an overwhelming bloc of hard-right Christian obscurantists.

Most of the contributors are theologians, informed by a melange of ideas, philosophical, historical and psychoanalytic. Perhaps the stronger of the essays are those that delve into the history of evangelism and religious revivalism in the US, uncovering a movement somewhat more complex than its current state would suggest; and those that ask a question decidedly missing from the rhetoric of bombastic atheism (Dawkins, Hitchens etc) – “not Do You Believe, But How Do You Come to Believe It?” as Magee puts it.

The aim is to interrogate the real roots of rightist religious revivalism – the actual material circumstances of those who believe. The intention seems to be an analysis of the roles of class, media and thought. Instead, though, what we get is a diverse but unsatisfying collection of academic musings on various topics connected with the politics of American religion.

The historical essays include Peter Goodwin Heltzel’s discussion of Evangelism, where he makes a distinction between “Prophetic” and rightist versions of this charismatic, fervent movement. He makes a fair case that the former has a more egalitarian bent and an attention to social justice not shared by the Televangelists, concentrating on Carl Henry, a collaborator of Billy Graham who held quasi-Leftist positions on various issues. Meanwhile Clayton Crockett attributes the rise of the Moral Majority to the South finally gaining a post-Civil War ascendancy, wreaking its resentment via a self-righteous spirituality that was notably absent before its defeat.

Where the contributors actually try to delve into the political circumstances of Christian dominance, the results are fairly predictable. America is depicted as militaristic, in hock to consumerism, addicted to media and devoid of any “meaning” to its existence (which is where the theologians come in). This much is apparent from innumerable books published since Karl Rove proved that pandering to religious prejudice was a guaranteed vote-winner, and there’s little here you couldn’t find in less academic texts.

The theoretical pieces are similarly problematic. Essays on concepts of Sovereignty or Lacanian psychoanalysis involve little more than potted summaries of their respective fields, clumsily given a politically current spin. This is a shame, as theory provides a potentially far more penetrating line of inquiry into America’s aggressive religiosity than the usual worried bafflement or huffing disgust.

Bizarrely, the most interesting issues are raised by Slavoj Žižek, who makes the extremely salient point that the rhetoric of the Religious Right is based on feelings – class resentment, anger, passion, collectivity – that were once the natural passions of radical politics. If the Religious Right is to be truly fought, the battle needs to be along these lines, rather than a mere apolitical horror at belief itself. This book could have been a contribution to such a battle, but earnestness finally lets it down – as does the persistent suspicion that the self-justifications of theologians rather than the urgencies of political practice are the real motivating factors here.

The Sleeping Giant Has Awoken is published by Continuum