In almost any city in the world today, if an African street trader offers you jewellery, belts or bags, he is almost certainly a Mouride, a follower of an Islamic sect founded in Senegal more than a century ago. Mourides are both a religious movement and a global trading company that has spread all over the world from Paris to Los Angeles, from Hong Kong to Dubai.

In almost any city in the world today, if an African street trader offers you jewellery, belts or bags, he is almost certainly a Mouride, a follower of an Islamic sect founded in Senegal more than a century ago. Mourides are both a religious movement and a global trading company that has spread all over the world from Paris to Los Angeles, from Hong Kong to Dubai.

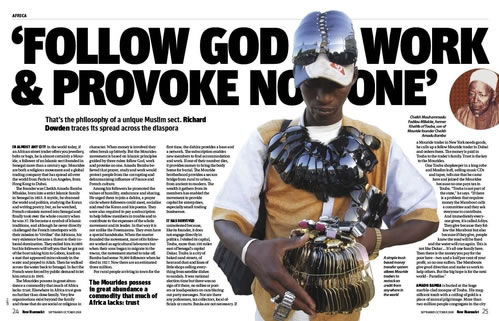

The founder was Cheikh Amadu Bamba Mbakke, born into a strict Islamic family in Senegal in 1853. A mystic, he shunned the world and politics, studying the Koran and writing poetry; but, as he watched, French colonists moved into Senegal and finally took over the whole country when he was 37. He became a symbol of Islamic traditions, and although he never directly challenged the French interlopers with their mission to “civilise” the Africans, his very existence became a threat to their colonial domination. They exiled him in1895 but his followers will tell you that he got out of the boat taking him to Gabon, knelt on a mat that appeared miraculously in the water and prayed to Allah. Then he walked across the water back to Senegal. In fact the French were forced by public demand to let him return in 1905.

The Mourides possess in great abundance a commodity that much of Africa lacks: trust. Elsewhere in Africa trust goes no further than close family. Very few organisations exist beyond the family and those that do are social or religious in character. When money is involved they often break up bitterly. But the Mourides movement is based on Islamic principles guided by three rules: follow God, work and provoke no one. Amadu Bamba believed that prayer, study and work would protect people from the corrupting and dehumanising influence of France and French culture.

Among his followers he promoted the values of humility, endurance and sharing. He urged them to join a dahira, a prayer circle where followers could meet, socialise and read the Koran and his poems. They were also required to pay a subscription to help fellow members in trouble and to contribute to the expenses of the whole movement and its leader. In that way it is not unlike the Freemasons. They even have a special handshake. When the master founded the movement, most of its followers worked as agricultural labourers but when their sons began to migrate to the towns, the movement started to take off. Bamba had some 70,000 followers when he died in 1927. Now there are an estimated three million.

For rural people arriving in town for the first time, the dahira provides a base and a network. The subscription enables new members to find accommodation and work. If one of their number dies, it provides money to bring the body home for burial. The Mouride brotherhood provides a secure bridge from rural to urban, from ancient to modern. The wealth it gathers from its members has enabled the movement to provide capital for enterprises, especially small trading businesses.

It has survived unmolested because, like its founder, it does not engage directly in politics. I visited its capital, Touba, more than 100 miles east of Senegal’s capital Dakar. Touba is a city of baked sand streets, of heat and dust and lines of little shops selling everything from satellite dishes to sandals. It was national election time but there was no sign of it there, no rallies or posters or loudspeakers on cars blaring out party messages. Nor are there any policemen, tax collectors, local officials or courts. Banks are not necessary. If a Mouride trader in New York needs goods, he calls up a fellow Mouride trader in Dubai and orders them. The money is paid in Touba to the trader’s family. Trust is the key to the Mourides.

One Touba shopkeeper in a long robe and Muslim kufi, selling music CDs and tapes, tells me that he came here and joined the Mourides because no one pays tax in Touba. “Touba is not part of the state,” he says. “If there is a problem that requires money the Marabout calls a committee and they ask everyone to contribute. And immediately everyone gives, it’s called Adiya. They give because they follow the Marabout but also because if they give, people know the road will be fixed and the water will run again. This is not like Dakar ... It’s all one family here. Then there is the money you pay for the poor here – two and a half per cent of your profit, so no one suffers. The Marabouts give good direction and make us work to help others. But the big hope is for the next world – Paradise.”

Amadu Bamba is buried at the huge marble-clad mosque of Touba. His magnificent tomb with a ceiling of gold is a place of annual pilgrimage. More than two million people congregate in the city for the great Magal every August, the two-day ceremony that commemorates his return from exile. The days are spent in prayer and the evenings in music, feasting and listening to the griots – the praise-singers. People are accommodated by the town and use the visit to buy tax-free goods more cheaply than anywhere else in Senegal. During the Magal delegations from the government and political parties are received by the Khalifa – a recognition of the political influence of the Mouride leader.

In Touba I was shown the Mourides’ peculiar handshake. The next time I used it was by the Ponte degli Scalzi in Venice a year later with two young African men selling Barbour handbags, trinkets and jewellery at a stall. They are astonished when I tell them that I learnt it in Touba. They had been in Venice two years and only go back when they are summoned.

In New York the dahira was founded by Bamba’s great-grandson in 1985. It will be the first place a Mouride visits when he comes to the city. It provides somewhere to stay, credit to trade and social support. Senegalese Mouride traders began importing African art and jewellery in the early 1980s and selling it on the streets. From New York they sent electrical goods and clothes – tax-free – to Touba and sold them all over Senegal and West Africa. The Mouride network then started bringing hats, watches, sunglasses, umbrellas and leatherwork from all over the world into New York. A simple trust-based money transfer system meant that all transactions between America and Africa could be done by telephone with the minimum of official scrutiny or paperwork.

In 2002 the New York Mouride community was estimated at about 7,000. Harlem has its “Little Senegal” area, complete with mosque, library and school. As in Touba, Bamba’s feast day is celebrated with a Grand Magal each year and New York now has several dahiras and an umbrella organisation which provides support for Mouride families in trouble and deals with the city council, the police and local politicians.

When you die, the Mouride organisations will fly your body home to Touba for burial. It is where all Mourides want to be buried. The Mourides also handle remittances to send back to Touba, donating some $8 million towards the completion of a modern hospital there. At the turn of the century the worldwide Mouride community was sending back an estimated $15–$20 million a year – about one-fifth of what Senegal received in direct foreign investment.

It is not as if Senegal is a collapsed or failed state. Senegal is one of the oldest European colonies in Africa. It sent deputies to the French parliament in Paris in 1848 and its borders were established in 1890. Apart from its southern province, Casamance, it has been stable since independence, with the present president, Abdullai Wade, only the third head of state. There has never been a hint of a military coup. Nor have there been bad rulers: Léopold Senghor stood down as president in 1981 and, after nearly two decades in power, his hand-picked successor Diouf lost the 2000 election to Wade and accepted the result.

But about one-third of Senegal’s population and all the leading musicians like Youssou N’dour and Cheikh Lo are Mourides, putting into a religious institution all the trust and taxes, obedience and commitment given by citizens to the nation state in most countries. And the religious organisation fulfils many of the functions and services of a welfare state as well as channelling its followers’ commercial energies. They also willingly give the Mouride movement a hefty “tax” on all their dealings.

In Senegal, and in Touba especially, the Mourides were open and welcoming, delighted that a foreigner should come and inquire about them. They even apologised when they found I had been refused entry to the mosque. “It must be open for everyone,” they said. In London, however, I have found them much more unwilling to meet or talk. Perhaps they are suspicious of Britain’s attitude to them, fearful of appearing on the radar at a time when immigrants feel under threat and Muslims are mistrusted. True to their philosophy of unobtrusive trade and prayer, they just want to be left alone.