In September, the London auction house Sotheby’s flogged £110m of signed Damien Hirst merchandise to starstruck admirers all over the world. In the days leading up to the sale, the culture pages were aflame with polemic. In the Guardian, the eminent Robert Hughes argued that “If there is anything special about this event it lies in the extreme disproportion between Hirst’s expected prices and his actual talent.” In the Evening Standard, his critical colleague Ben Lewis stated: “There is no originality here, and plenty of pomposity. This is not art that is developing, but art that is turning in on itself, whose only notion of progress is greater scale and expense. This is work by an artist who thinks the shinier it is, the better it is.”

In September, the London auction house Sotheby’s flogged £110m of signed Damien Hirst merchandise to starstruck admirers all over the world. In the days leading up to the sale, the culture pages were aflame with polemic. In the Guardian, the eminent Robert Hughes argued that “If there is anything special about this event it lies in the extreme disproportion between Hirst’s expected prices and his actual talent.” In the Evening Standard, his critical colleague Ben Lewis stated: “There is no originality here, and plenty of pomposity. This is not art that is developing, but art that is turning in on itself, whose only notion of progress is greater scale and expense. This is work by an artist who thinks the shinier it is, the better it is.”

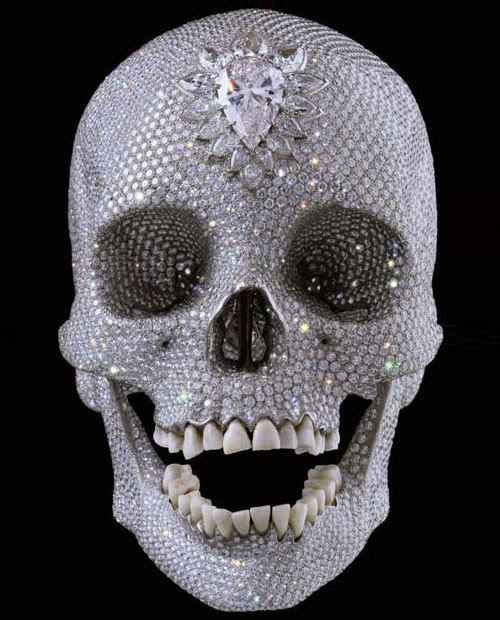

On the evening of the auction, Lewis could be seen agitatedly pacing New Bond Street after being turned from the door for precisely this kind of commercially unhelpful opinion. A pity he missed out on a curious detail to be found within the auction itself. For some peculiar reason, the auctioneer Oliver Barker chose to orchestrate proceedings in front of a lurid Technicolor painting of a skull. As Barker winked and cajoled and hammered away at his lots, the skull glared enigmatically at the audience from behind him, seemingly asking: “What can I mean?”

One possible (if mildly malicious) explanation is that the skull stood for the death of the traditional dealership system. Until recently, business in the art world – like business on Savile Row – was conducted behind closed doors, and by appointment only. In an industry where reputation is everything, the hands through which a work has travelled have been just as important to its monetary value as the artistic talent it showcases. Cognisant of this fact, dealers in the past have sought to carefully manage their client lists, only offering the works of their artists to a small number of hand-picked collectors in possession of the right reputations.

At Sotheby’s in September, this quasi-feudal model was emphatically breached.

Hirst’s artistic career has paralleled and perhaps hastened the collapse of this system, and he embodies in his person the new shape that the art market is taking. Offering a portrait of the artist as a multinational corporation, Hirst proposes a model of art that is no longer concerned with traditional practices such as self-expression or even conceptual criticism, and instead concentrated on more commercial questions like cross-platform branding strategies and marketing initiatives. As such he completes the work begun by Andy Warhol, former city trader turned artist Jeff Koons, and Charles Saatchi. He is not closing the gap between art and commerce, but making art essentially commerce.

In Seven Days in the Art World, a book that tracks these changes in the structure of the art market, Sarah Thornton captures the specious logic governing prices at auctions: “A ‘good Basquiat’ for example,” she writes, “was made in 1982 or 1983 and contains a head, a crown and the colour red. Primary concern is not for the meaning of the artwork but its unique selling points, which tend to fetishise the earliest traces of the artist’s brand or signature style.” All of Hirst’s work fits this pattern. Deploying a minimal matrix of elements, endlessly recombined and reconfigured, his butterflies, spot paintings and butterfly spot paintings are like the combinational flavours of soft drinks: Cherry Coke, Diet Coke, Diet Cherry Coke.

Both Hughes and Lewis, and others, dismiss this aesthetic as shallow and vapid. In doing so, though, they miss something crucial. If art is a mirror held up to the world, Hirst’s continuing prominence and his carefully tailored aesthetic do capture fairly acutely the kind of world we now inhabit. His best work overtly proclaims his own strategies: his butterfly paintings, produced by treating canvases with sugar solution in order to lure instinct-led creatures to sticky transfixion perfectly, symbolise his skill at capturing and holding the right kinds of attention; his sharks in formaldehyde offer triumphant allegories of his own predatory talents in converting the financial sharks of the global economy into his stuffed and trussed-up, free-spending thralls. The pièce de résistance presented at Sotheby’s was Hirst’s golden calf, an image of greed and idolatry so straightforwardly brazen that it sold on the night for £12m.

“Who could have bought that piece?” one incredulous but enraptured critic standing next to me whispered, “Scarface?” The work seemed at once so stupid and clichéd as to defy all estimations of artistic merit, financial or otherwise. Yet significantly, at the Sotheby’s exhibition preceding the auction, the sum each work was expected to fetch was displayed in the same font and colour as their ostensible titles – as if their value were an essential part of their meaning. In the case of an artist whose singular skill consists in his ability to turn images into cash, the touch was a fitting one. After all, money itself now represents Hirst’s true medium.

Hirst’s triumph at Sotheby’s coincided to the day with the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, an event which set in motion the presently raging whirlwind of financial catastrophe. This coincidence, combined with the subsidiary fact that the world’s current economic problems appear to have been caused largely by the very same people who buy Hirst’s work at auction, makes it easy to see the former as in some sense the ultimate expression of the latter: the artistic icing on the cake of a hollow and crazy financial system.

This temptation recognised, though, it would be more accurate to understand Hirst as arising from an older condition which in truth underpins both art and the economy. This is the condition of perpetual status-seeking, which is an evolutionary principle as well as a sociological one. The capitalist tendency to worship abstract numbers and labels, as in the sizes of salaries or the grandeur of titles (as well as in the doctrine of seeking to stimulate growth at all costs, whether through arms spending and slave trading or otherwise), is an expression of a deeper fixation on quantifiable and objective status, out of which capitalism first arose. Artists too are complicit in this eternal status game. Art is a public and cut-throat activity which actively seeks to elicit the attention of others. Ultimately, it is a human endeavour which, like all such endeavours, involves uglier feelings and baser emotions than many of its advocates – or critics – appear willing to admit.

Art has always been joined at the hip to ruling elites and symbolic prestige: suffice to say, there is no Sistine Chapel without the Church, and no Dutch Old Masters without a bourgeois market for portraiture. This is as true in our own times as it has ever been, the only significant difference being that the nature of ruling power has changed, causing art to change around it. This shift appears threatening in the eyes of aesthetic and intellectual conservatives, who long to get back to the good old days, whenever they were, and then contrive to live there. Yet their attitude is really one of nostalgia and hopelessness, and in the end they have nothing more to contribute.

“This world is a tragedy to those that feel,” wrote Horace Walpole, “and a comedy to those that think.” From a feeling perspective, contemporary art, which reflects the state of the world, and so often presents an ugly side of that world, appears bankrupt and decadent. But to treat art like a voodoo doll is superstitious and crazy. In the end every epoch gets the art it deserves, and wherever else our sentimental attachments might lead us, we have no right to despise the present.