I walk the first half-mile. Across the Farringdon Road, over Clerkenwell Green, and then at the beginning of Seckforde Street I pause to check that my laces are tightly tied and wait until the big hand on my watch reaches the top of a minute. And then I start to run.

I walk the first half-mile. Across the Farringdon Road, over Clerkenwell Green, and then at the beginning of Seckforde Street I pause to check that my laces are tightly tied and wait until the big hand on my watch reaches the top of a minute. And then I start to run.

The first steps are always the toughest. My feet feel as though encased in concrete and my legs which looked like perfectly normal functioning legs as I was pulling on my track suit now seem to have about as much capacity for independent movement as a pair of pipe cleaners. I’m not so much running as stumbling forward into the unsustaining air like a late night drunk.

Round the corner of Skinner Street, into the little park behind Exmouth Market, and on to the circular path which bounds the grassy No Dogs area where people exercise their dogs.

I’m going to run 20 times round this path. A full half hour.

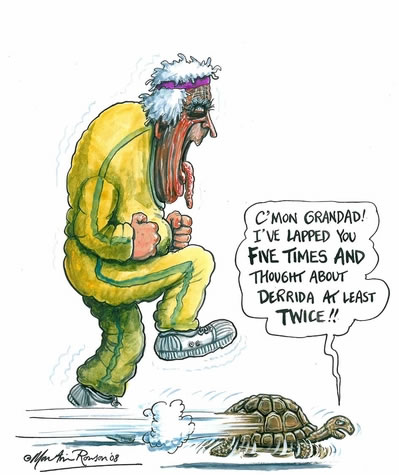

On most mornings I have a small audience. Local dossers who have woken from a cold uneasy slumber on the benches which line the track often barrack me as I pass them for the first or second time. “Get ‘em up, Grandad.” “Come on, Sebastian.” But they soon tire of the jokes as I metronomically pass them again and again.

A much greater concern is other walkers. I’m moving so slowly as I come up behind them that they mistake me for a stalking mugger and can react with such alarm that I’ve taken to humming a little reassuring tune as I approach their backs.

Until recently I endeavoured to make the minutes pass as quickly as possible by listening to my miniature radio but I soon found that I was becoming so irritated by one of the guests on Start the Week or all the guests on Midweek that the time was becoming extended rather than shortened.

Nowadays I try to go in for thinking. It’s all to do with having read a little book by the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami called What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Murukami is a real runner. He’s done dozens of marathons around the world but there are any number of gentle insights in his book which seem applicable to even the most laborious plodder. He tells me for example that the thoughts which occur to him while he is running are like clouds in the sky. “Clouds of all different sizes. They come and they go, while the sky remains the same sky as always. The clouds are mere guests in the sky that pass away and vanish, leaving behind the sky. The sky both exists and doesn’t exist. It has substance and at the same time doesn’t. And we merely accept that vast expanse and drink it in.”

Now that is obviously a rather beautiful set of thoughts. A bit on the zen side of things but still beautiful. And extensive. That’s my problem with running thoughts. They simply won’t stick around for long enough to provide a sufficient distraction from the pain which is developing in my left ankle, the stickiness of the accumulating sweat on my T-shirt, the cold knowledge that although I seem to have been running for several hours I’m still only at the beginning of my fourth circuit.

I even prepare my running thoughts on the way to the track. Today, I say to myself, I will go in for a concentrated think about the definition of rationalism which I’ve promised to prepare in time for the next Board meeting of the Rationalist Association. Today I will devote the full half hour to an extensive think about Foucault’s theory of sexuality which I’m due to discuss on my next radio programme.

But the thoughts never stay around. No sooner are they in my mind than they slide out of consciousness like a fresh egg scuttling across a Teflon frying pan. One second I am thinking hard about the definitional differences between humanism and rationalism and the next I am giving serious cognitive attention to whether or not I should break with tradition when I next go shopping at Sainsbury’s and buy the yoghurt with a separate section of honey on the side or buy plain yoghurt and mix in my own strawberry jam. A second after that I’m wondering whether the slight pain that’s now developing in my chest is the first hint of a minor cold or hard evidence of the onset of terminal lung cancer.

There is only one thought that recurs and recurs. The thought that comes to me as an elderly lady pulling a shopping trolley overtakes me as I reach my finishing line opposite the Guardian building in Farringdon Road, the thought that comes to me as I reach home and have to lie down to recover from my exertions: the thought that all my athletic endeavours to stave off an early death are killing me.