“I must ask you as a Christian and as a Bishop – why do you think Mr Scargill keeps up mass picketing?” wrote the then Energy Secretary Peter Walker to the Bishop of Durham on 5 October 1985.

“I must ask you as a Christian and as a Bishop – why do you think Mr Scargill keeps up mass picketing?” wrote the then Energy Secretary Peter Walker to the Bishop of Durham on 5 October 1985.

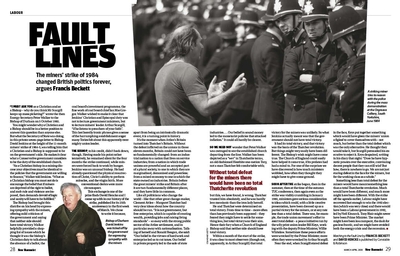

You might wonder why a Christian and a Bishop should be in a better position to answer this question than anyone else. But what the Secretary of State was doing, in this private seven-page letter to Bishop David Jenkins at the height of the 11-month miners’ strike of 1984-5, was telling him that a Christian and a Bishop is supposed to be on the government’s side. He makes it clear what a Conservative government considers to be the duty of the established church.

“As a Christian bishop in a mining diocese your objectives must be identical to the policies that the government are willing to finance,” Walker told Jenkins. “What as a Christian bishop you must not do is encourage the belief that if miners are deprived of the right to ballot, and mob rule and violence are imposed, then demands devoid of logic and sanity will have to be fulfilled.”

The Bishop had brought this diatribe on his head by expressing sympathy with the miners, offering mild criticism of the government and saying that neither side should have total victory. Walker helpfully provided a shopping list of issues which he thought it was the bishop’s Christian duty to talk about: the absence of a ballot, the coal board’s investment programme, the fine work of coal board chief Ian MacGregor. Walker wished to make it clear that Jenkins’ Christian and Episcopal duty was not to lecture government ministers, but to lecture miners’ leader Arthur Scargill, “if he listens to preachers of your faith”. This last heavily ironic phrase gives a sense of the harrumphing establishment anger many Tories felt about this apparently over-mighty union leader.

The Bishop, to his credit, didn’t back down, though. Having made his point rather tentatively, he remained silent for the four months the strike continued, while miners were forced back to work by hunger. Jenkins was an unusual bishop. He had already questioned the physical resurrection of Christ, Christ’s ability to perform miracles, and the virgin birth. More conventional clerics were more circumspect.

This exchange is one of the prize finds David Hencke and I came up with in our history of the strike, published for its 25th anniversary in the first week of March. We chose to write it because, apart from being an intrinsically dramatic event, it is a turning point in history.

It’s the moment when Attlee’s Britain turned into Thatcher’s Britain. Without the defeat inflicted on the unions in those eleven months, Britain could not have been so fundamentally changed: from an industrial nation to a nation that lives on service industries; from a nation in which trade unions are powerful and an accepted part of a plural society, to one in which they are marginalised, demonised and powerless; from a mixed economy to one in which the state owned no industries. Britain before the great miners’ strike and Britain after it are two fundamentally different places, and they have little in common.

Like all politicians who change the world – like that other great change-maker, Clement Attlee – Margaret Thatcher had very clear ideas about how the country should be run. “It is not government, but free enterprise, which is capable of creating wealth, providing jobs and raising living standards” – so away with the strong public sector of the Attlee settlement, and in particular away with nationalisation. Talking of herself and Ronald Reagan, she said: “Our belief in the virtues of hard work and enterprise led us to cut taxes. Our belief in private property led to the sale of state industries . . . Our belief in sound money led to the monetarist policies that attacked inflation.” It could all hardly be clearer.

So we need not wonder that Peter Walker was outraged to see the established church departing from the line. Walker has been depicted as a “wet” in Thatcherite terms, an old-fashioned Heathite one-nation Tory, not a man Thatcher felt comfortable with; but this, we have found, is wrong. Thatcher trusted him absolutely, and he was hardly less messianic than the iron lady herself.

He and Thatcher were determined on total victory. From time to time – more often than has previously been supposed – they feared they might have to settle for something less, but total victory was their aim. Hence their fury when a Church of England Bishop said that neither side should have total victory.

Within a month of the start of the strike, it was clear to most observers (though not, apparently, to Arthur Scargill) that total victory for the miners was unlikely. So what Jenkins actually meant was that the government should not have total victory.

It had its total victory, and that victory was the basis of the Thatcher revolution. But things might very easily have been different. The Bishop’s wish might have come true. The Church of England could easily have helped it come true, if its prelates had had a mind to. For one of the surprises we have discovered is how much ministers wobbled, how often they thought they might have to give some ground.

Soon after the strike began, then in the summer, then at the time of the autumn TUC conference, then again even as the strike was visibly crumbling in January 1985, ministers gave serious consideration to ideas which could, with a little creative presentation, have been dressed up as a partial victory for the miners, or at any rate less than a total defeat. There was, for example, the trade union movement’s effort to avert total defeat – a peace initiative run by the wily print union leader Bill Keys, working with the deputy Prime Minister, Willie Whitelaw. Sometimes these peace efforts were wrecked by the Prime Minister; more often they were wrecked by Arthur Scargill.

Near the end, when Scargill stared defeat in the face, Keys put together something which would have given the miners’ union a figleaf to cover themselves with – not much, but better than the total defeat which was the only alternative. He thought they would take it, but Scargill persuaded his executive to reject it. Keys despaired, writing in his diary that night: “Does he have hypnotic powers over the executive, convincing decent people that they can still win? But how, there is nowhere to go. We are not just staring defeat in the face for the miners, but for the working class as a whole.”

Something less than total defeat for the miners would have meant something less than a total Thatcherite revolution. Much would have been different, and much more might have been different. With the strike off the agenda earlier, Labour might have recovered fast enough to win the 1992 election (which was very close) and there would have been a Labour government in 1992, led by Neil Kinnock. Tony Blair might never have been Prime Minister. The market might have been less rampant, the dash for gas less frantic, and we might have avoided both the energy crisis and the recession.

Marching to the Faultline by Francis Beckett and David Hencke is published by Constable & Robinson