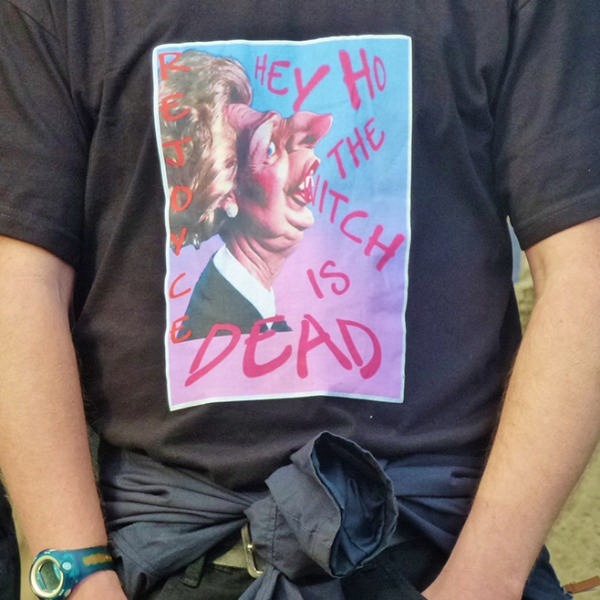

As India approaches seventy years of independence and the 150th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday, his life has turned from biography to myth, and finally into product. Gandhi T-shirts feature him walking with a stick, always smiling with approval. There are Gandhi posters and fridge magnets.

Even during his lifetime, the glare from Gandhi’s reputation eclipsed his contemporaries and rivals: Lord Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. When Gandhi travelled in India, he was met by crowds of between 10,000 and 20,000 ardent followers. After he died in 1948, millions would attend his state funeral amid scenes of confusion and turmoil. His ashes were scattered in two continents, across India in 1948 and, over 60 years later, off the coast of Durban in South Africa.

The aura which surrounded Gandhi in life shows no signs of dimming. Protesters taking part in demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011 held photographs of Gandhi. His life and writings have inspired Martin Luther King (who received the Gandhi Peace Award in 1964), Desmond Tutu, Aung San Suu Kyi and Nelson Mandela. He has been compared to Jesus, to Buddha and to Saint Francis of Assisi.

While Gandhi’s struggle to liberate India from British rule has drawn the attention of dozens of biographers and historians, his time in South Africa – where he worked as a lawyer from 1893 to 1914 – is either forgotten or half remembered. He is commemorated primarily though monuments and tributes. The central hub of Johannesburg’s business district is called Gandhi Square. A statue in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, has Gandhi dressed in his familiar khadi, his right arm outstretched in blessing. Fordsburg, a suburb of Johannesburg, is the site of the Gandhi Memorial or Burning Truth, a cauldron which recalls the burning of identity papers by Indians in 1908.

Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed’s new book, The South African Gandhi, is not the first attempt to scrub his life free of the dust of iconography. Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India by Joseph Lelyveld (2011) is a calm and clear-eyed portrayal of an Indian leader often overcome by public and private obligations. Lelyveld’s Gandhi is a flawed and occasionally exasperated leader whose life is knotted by his expectations of Indians and the cruel disappointment of Partition.

The historian Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India (2013), the first of two biographies from the author, draws a rich path in Gandhi’s evolution from avowed Anglocentric lawyer to battling brahmacharya. From defending British rule, Guha’s Gandhi returns to India to reject Western modernity for social justice, spirituality, self-sufficiency, religious freedom and an end to colony. More will follow: Gandhi’s own Collected Works, a forthcoming archive of writings and speeches, will run to a hundred volumes.

When Gandhi arrived in Durban, South Africa in 1893, he was a 23-year-old economic migrant. He had been born in 1869 into a traditional merchant family in Porbandar, a small coastal town in Gujarat with a population of around 15,000. Hindus wove cloth made of silk and cotton which their Muslim neighbours sold in Zanzibar, Cape Town and the Middle East. Gandhi studied and trained as a lawyer in London for three years. He ate porridge for breakfast, learned elocution and ballroom dancing, and wore a black suit. On returning to India as a barrister, he tried to find work for two years before taking a job as a law clerk in South Africa.

He entered adulthood on a continent at the mercy of the civilising rod of the British Crown. It was an era of mass industrialisation facilitated by ruthless subjugation. Millions of Indian men, women and children, predominantly Tamil, Telugu and Bihari labourers, were dispatched to colonies like South Africa to mine raw materials and work on plantations. Those who stayed behind were forced to leave their families and villages and build roads and railways to feed Empire. By 1913, 88 per cent of South African exports reached the United Kingdom.

In 1893, when Gandhi arrived at a court in Durban and was asked to remove his turban by an English magistrate, there was little to suggest his future life of activism. His first serious brush with colonialism occured on the first-class carriage of a train to Pretoria where he was due to spend a year. A European passenger ordered Gandhi to sit in the carriage reserved for Africans. Gandhi complained to a train official who, in turn, summoned a constable. The architect of non-violent protest spent the night shivering in a cold and dark waiting room in a railway station after being forcibly removed from the train.

Like many Indians, Gandhi held fixed views on race and caste. He saw Africans as inferior and sought to align Indians with their colonisers. Gandhi trusted Queen Victoria’s empire would eventually extend the same rights and privileges – in theory at least – to all its Indian subjects. He would write later, in 1914: “(Although) Empires have gone and fallen, this Empire perhaps may be an exception. This is an Empire not founded on material but on spiritual foundations. That has been my source of solace.”

In Pretoria, however, after meeting with other Indians, Gandhi had begun to evolve. He learned that Indians were bound by a range of “disability laws”. They were denied the vote, banned from walking the city’s streets after 9pm and allowed to purchase only leasehold property in designated areas. The same laws stipulated they pay an annual tax of £3 per head.

His humiliation was deepened when he returned to Durban and learned of proposals which would remove Indians from the voting register. Within two weeks, Gandhi mobilised the city’s Indian population and gathered over 10,000 signatures from labourers, clerks, shopkeepers and traders. Gandhi’s burgeoning protest movement would prove to be the template for revolt in India, taking the form of public meetings, newspaper articles and open letters to British officials attacking racist legislation. He established a permanent organisation to fight for their rights called the Natal Indian Congress. People flocked to see “Gandhibhai” from miles around and his reputation spread to political circles in both the United Kingdom and India.

When the Anglo-Boer War erupted in 1899, Gandhi offered the services of the Natal Indian community to the military as a volunteer stretcher-bearing unit. Most Indians sought to stay out of the conflict for fear of reprisals, but Gandhi saw it as an opportunity to secure concessions for Indians. Lord Herbert Kitchener had embarked on a scorched-earth policy to flush out guerrilla fighters. Boer woman and children were interned in concentration camps and thousands died of malnutrition, measles, typhoid and pneumonia. “It would a great disappointment, if after all arrangements, [the] government would not accept us,” Gandhi wrote.

Desai and Vahed devote considerable time to analysing Gandhi’s early views on race. When the Johannesburg Municipality allowed a number of Africans to live near Indians in 1903, Gandhi complained the council “must withdraw the Kaffirs from the Location. About this mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians, I must confess I feel most strongly. I think it is very unfair to the Indian population and it is an undue tax on even the proverbial patience of my countrymen.” When it was suggested that Indians might relocate to a site close to an African development outside of Johannesburg, Gandhi objected strongly. Indians, he said, “were amenable to sanitary control, surely there can be no objection against him as a neighbour.”

Gandhi was not unique in separating the Indian struggle from other injustices. For as long as Indians had lived in South Africa, they had maintained a wary distance from Africans. Johannesburg already exhibited all the hallmarks of apartheid. Africans were forced to carry identity papers, excluded from public spaces, banned from walking on pavements and confined either to “kaffir locations” in mines or the servant quarters of their employers.

In South Africa, during the years 1903 and 1904, Gandhi began to develop what would later be described as Gandhi-ism. He launched the Indian Opinion newspaper in 1903 in Durban to voice grievances and educate Indians in matters of health, spirituality and philosophy. The newspaper also had a reformist agenda and published extracts from books by Tolstoy, Thoreau, William Salter, W.E.B. Du Bois and poetry by Omar Khayyam. Indian Opinion, however, took little notice of caste, women’s issues, slavery and the many hardships endured by black South Africans.

The year 1904 would also see Gandhi begin to focus on self-knowledge and spiritual strength. He purchased a farm of a hundred acres at Phoenix on the north coast of Natal. Greed and material comforts were all rejected for satyagraha – satya is “truth” or “soul” while graha implies firmness or force. According to Gandhi, “We can free ourselves of the unjust rule of the Government by defying the unjust rule and accepting the punishments that go with it. We do not bear malice towards the Government.”

Life at Phoenix was austere. Food was only consumed at mealtimes; salt, ghee and milk were outlawed. Residents performed chores like cleaning bedpans, sewing clothes and growing crops. The farm at Phoenix was no New Age paradise. Transgressions would lead to public humiliation. Conditions were so severe that Gandhi’s son Harilal would write a 32-page booklet, My Open Letter to my Father M.K. Gandhi, in which he criticised the grim conditions for residents. “I have not the words to describe the misery Mother went through,” he wrote.

Another transformation would occur with the outbreak of the Zulu Rebellion in 1906. The British had annexed Zululand in 1887, provoking an uprising from Zulu farmers. Gandhi organised another Indian volunteer ambulance corps but, when they arrived in Zululand, he saw the rebellion was being repressed by public hangings and floggings. The suffering had a profound effect on Gandhi and he vowed to make serving humanity his life’s work.

The apex of this commitment was the 1906 introduction of the Asiatic Registration Bill, making it mandatory for Indians to be fingerprinted and issued government registration certificates. These were to be carried at all times. Punishment ranged from fines to imprisonment and deportation. The law came into effect in 1907 and an outraged Gandhi spent his remaining years in South Africa resisting the “Black Act” with periods of imprisonment and voyages to London where he lobbied the Raj for its repeal.

When Gandhi returned to India in 1914, the main provisions of the “Black Act” remained intact, but he had negotiated compromises. The head tax was abolished and South Africa would take no more indentured Indian labourers after 1920. While Gandhi would depart without achieving any discernible victories for the country’s native population, his two decades in South Africa saw the maturing of ideas he would employ for the rest of his life. The period also saw the birth of his disappointment with the British Empire. He wrote: “…it was a great wrench for me to leave South Africa where I had passed twenty-one years of my life sharing to the full in the sweets and bitters of human experience, and where I had realised my vocation in life.”

Men and women who wield extraordinary power are rarely immune from error. Malcolm X reached outside the Black Muslim periphery only after leaving the Nation of Islam in 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s liberal domestic agenda was overshadowed by the war in Vietnam. Tony Blair’s place in history is defined by his decision to ally with President George W. Bush; his modernising of the Labour Party is largely unacknowledged.

In the years since apartheid and reconciliation, South Africa’s politicians have often paid tribute to Gandhi as a fellow warrior on the path to majority rule. His legacy overlooks early inconsistencies and oversights. “He was both an Indian and a South African citizen,” said Nelson Mandela in 1999. “Both countries contributed to his intellectual and moral genius, and he shaped the liberatory movements in both colonial theatres.”

Desai and Vahed have provided valuable insight into the early life of Gandhi and the struggle that would see him embody universal courage and empathy. His life occasionally endured failure and suffered from the prejudices of the day. Yet whenever a large social movement emerges to call for change and an upending of the old order – the Arab Spring and Black Lives Matter are two recent examples – the agents of change always look to the life of Gandhi for counsel and inspiration.

“The South African Gandhi” is published by Stanford University Press