Please welcome Russell Crowe and Helen Mirren." I felt in my inside pocket for my glasses. Halfway back in the Circle of the Empire, Leicester Square, is not the best place for a close-up of the stars of the new film State of Play. I might not have bothered at all but as I'd only been able to gain entrance to this world premiere by walking along a red carpet flanked by barricaded fans longing for the merest glimpse of the superstars it seemed churlish not to have an ogle when they were sharing the same auditorium.

Please welcome Russell Crowe and Helen Mirren." I felt in my inside pocket for my glasses. Halfway back in the Circle of the Empire, Leicester Square, is not the best place for a close-up of the stars of the new film State of Play. I might not have bothered at all but as I'd only been able to gain entrance to this world premiere by walking along a red carpet flanked by barricaded fans longing for the merest glimpse of the superstars it seemed churlish not to have an ogle when they were sharing the same auditorium.

Glasses, though, weren't quite enough. I'd have needed a good hearing aid to catch the full sense of the stars' mumbled bouts of mutual congratulation. But the rest of the audience applauded ecstatically as though they'd each been thrown a personal bouquet and then settled back to watch a movie which the blurb told me was "an outstanding electrifying scorching thriller which grips from start to finish".

It was good but not that good. And certainly its grip was not tight enough to prevent me occasionally remembering how close I once came to being a movie star in my own right, someone to be passionately clicked at as I walked down a premiere red carpet, rather than as tonight when my arrival had provided nothing more than a moment for the snappers to take a pull on their take-away coffees.

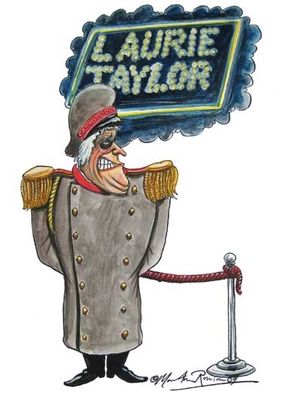

My brush with stardom goes back nearly 40 years, to the time when I was employed as a linkman, just 50 yards across the Square, at the Odeon. I was told at my interview that despite the similarities in function, a linkman was very much more than a doorman. Once I was garbed in my brown gold-braided uniform and peaked cap, I was to regard myself as a "conduit" between the punters and the cinema. I had, when asked, to be able to provide a brief synopsis of the film, explain where they might park their cars and provide an accurate assessment of their chances of getting in to the next showing.

But my big moments would be reserved for premiere nights, when I would be required to wait at the pavement end of the red carpet for the star to arrive in their limousine. At this point my task was to walk to the car door with my head down so that I did not intrude on the star's majesty with my secular eyes, and then wait while the star eased his or herself out of the back seat and launched themselves on to the red carpet. Only when I'd seen the star safely on to the carpet could I shut the limo door firmly behind them.

Sadly, my one and only premiere was a mediocre film called Blind Date starring Hardy Kruger. But the red carpet and the crowds were still rolled out and I dutifully stepped up to meet the arriving car. With lowered eyes I yanked open the door and waited. And waited. And waited. But still nobody appeared. Not even a shadow of a figure passed across the car window that I held clasped to my chest.

I was beginning to wonder if this was a particularly blatant example of a star endeavouring to raise the waiting crowd to a state of hysteria when I heard a voice from the depths of the limo. "Shut the fucking door," bellowed the driver. I did as I was told and turned to face the Odeon entrance. And there, already three-quarters of the way along the red carpet, was Hardy Kruger. He was, I later realised, so diminutive that he'd simply bypassed my eye-line through the window as he descended.

Just one week afterwards I learned the full extent of my missed opportunity. Word spread around the ill-assorted workers of Leicester Square that something truly amazing had happened outside the Empire. It seemed that Michael Redgrave had been attending a premiere at that cinema but as he stepped out on to the carpet he couldn't help but notice the linkman who'd helped him from his car. He asked the man his name. Took his address. Contacted him next day. Put him in a film. And made him a star.

The linkman's name was Stephen Boyd. You must remember him. He actually co-starred with Brigitte Bardot in The Night Heaven Fell, won a Golden Globe for his performance in Ben-Hur, and was the first choice for many years in any film that called for a tough-looking actor with an aptitude for wearing heavy Roman armour. He had an unhappy end. He died of a heart attack playing golf in California when he was only 45.

When I told the story to Geoff, my companion at the premiere, he was somewhat less inclined than myself to see the whole episode as an example of how near I came to Hollywood stardom and a proper place on the red carpet. In truth, he babbled rather ungenerously about statistical probability and the predilection of lightning for single strikes.

He only had one word of real consolation. "Think of it this way," he said as we crossed the road to the French House. "Would you rather be a living sociologist or a dead film star?" I told him I'd have to think about that one.