“Read your own obituary notice,” Leopold Bloom muses in Joyce’s Ulysses, “they say you live longer. Gives you second wind. New lease of life.”

If you could do with some quickening of the blood this autumn but would rather get out of the house, you might try flâneuring your way down to London’s National Gallery to see “The Sacred Made Real”, an exhibition of 17th-century Spanish Christian art. Featured will be paintings and sculptures by such master realists as Diego de Velázquez, Pedro de Mena, Gregorio Fernández and the “Spanish Carravagio” himself, the great Francisco Zurbarán. If you had forgotten how lucky you are to have your health, then this show should pump some existential appreciation back into your veins – give or take a nightmare or two.

From 21 October to late January, gallery-goers will be confronted with an onslaught of bruisingly realistic and grotesque imagery: Christ pulverised and collapsing in his manacles, sagging in agony on the cross, or lying dead, with wounds you could stick your finger in, eyes rolled back, bleeding from ear to orifice; St Francis, in all-too-human bodily solidity, gazing forlornly up into the dark, inscrutable heavens; a weeping Mary, in meticulously sculpted and tinted polychrome, so lifelike you want to bring her a cup of tea and a handkerchief .

This is all a very far cry from the coffee-morning and carol-singing aesthetic we tend to associate with modern Christianity. Indeed, National Gallery director Nicholas Penny has acknowledged the potential for distaste in displaying such grisly expressions of mortal anguish, but insists – rightly – that it would be patronising to the viewing public never to invite them into challenging territory. Besides, this kind of shiversome, blood-encrusted spectacle has always played an essential role in Christianity’s appeal, even if much of it has become familiar to the point of indifference – the faith’s key symbol, after all, is a bedraggled, bleeding, expiring human being hanging limply from a Roman instrument of torture, caked in the gore of a medley of stab wounds and whip lacerations and garnished with a bouquet of flesh-puncturing thorns.

What is the fascination with this stuff? There is its purely aesthetic power, of course. The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Francis Hutcheson insisted that artistic depiction of even the ugliest subject matter could be intensely pleasing – something he called “representative beauty”. This accounts for the aesthetic delight of, say, Rembrandt’s gutted bovine carcasses or Van Gogh’s grisly, mutilated self-portraits. Yet, as the German philosopher Hans Gadamer insisted, a piece of art always contains a truth claim, a statement of the existence of a certain state of affairs in the world that is inseparable from the aesthetic experience of the artwork.

And in order to deliver their message these works, all too clearly, go much further than any merely representative impression of human mortality. Rather, they lavish attention upon every aspect of real, bodily death, obsessing over every oozing earhole, gored groin and tenderised tendon, until the effect goes way beyond one of otherworldly meditation – this, they cry out, is the living reality of death itself. Gregorio Fernández’s sculpture “Dead Christ”, for example, is stunningly gorgeous in terms of artistic finish, but it might have been inspired by the bonus extended flagellation scene from Mel Gibson’s anti-Semitic sado-masochistic bonanza The Passion of the Christ.

Laying aside beauty, then, it is undeniable that there is something deeply gratuitous in the impulse that creates such works, a will to displace mere aesthetic wonder and awe in favour of the bludgeoning power of shock, nausea and horror. And yet the effect of such work on the average 17th-century churchgoer was, as art historians such as Simon Schama have observed, intensely spiritual. This is the central paradox in a great deal of Christian art, and indeed in Christianity itself, whose very power, as Kierkegaard pointed out, was centred in the bizarre paradox of an immortal god manifesting himself as mortal man – the infinite entering the temporal; the immaculate touching the earthly. Contemporary viewers were both appalled and comforted by this visceral realism, which, despite a corporeality that one could almost smell, held the power of revelation for them, a power that lies in the fact they are both symbolic and literal, simultaneously representing the metaphysical structure of reality professed by the Church while also showing in graphic detail the suffering that must be undergone in this world before the gates to a better one open.

If worshippers of the age were in any doubt as to how their own festering bodily suffering related to the moral precepts expounded by priests and their scriptures, then these paintings rounded out the connection in graspable solidity. Life might seem to consist of nothing but suffering, but with art that placed this suffering unflinchingly in the foreground the Church affirmed the point that that was the point. Christ himself had experienced that same sense of forsakenness in undergoing an infinitely more awful ordeal than most plebs could expect to die from – the suffocating, tendon-popping, flesh-rending agony of crucifixion – but he transcended it, conquering worldly pain to enter paradise.

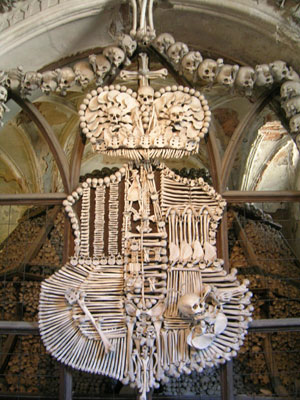

Looking elsewhere in Christian art, one can find even more direct manifestations of this will to appal. Take a look, for example, at Sedlec Ossuary, a small Catholic chapel in the Czech Republic, lying just east of Prague. This outwardly unremarkable little church is lavishly decorated inside with the bones of over 40,000 human bodies amassed since the 12th century. Entering at its main door, one comes face to face with standing plinths bearing skulls resting atop humerus bones. More skulls, hundreds of them, line the stone ribs of the vaulted ceiling and the curves of the arches leading into the alcoves and chancels. Towards the rear, a decorative shield is made up of row upon row of tibias, ulnas, radiuses, metacarpals, mandibles, scapulas, ribs, lumbar vertebrae, manubriums and phalanges. At the top of it, yet more skulls are enframed by white blossoms formed by fanned pelvic girdles. In the center of the nave, an enormous white chandelier looms from the ceiling, made entirely of osseous matter, and including at least one of every bone in the human body.

All the words I can think of to describe the effect seem rather hackneyed. But words such as “uncanny” or “awesome”, taken in the tenor with which they were once used, can get us somewhere near it – one really is struck with awe. Like the work of the Spanish realists, its power seems to lie in the fact that the spectacle is both symbolic and literal at the same time. That’s to say that the bones represent a symbolised, mythopoeic death, while also being the leftovers of the process of real, bodily death. Whereas most symbols gesture away to some comfortably distant paradigm, these ones are themselves what they mean. Forget Marshall McLuhan – these bone artists had already figured out centuries ago that the medium is the message.

And again, there is something unequivocally gratuitous here, the wilful presentation of death in its immediate, grisly reality in order to cow churchgoers into accepting that in the absence of anything to comfort and redeem in this world, adherence to dogma will guarantee passage to a nicer one. Such morbid exhibitionism is a standard tactic of the Catholic Church, of course, being effected by way of theatrics, ritual, recitation, gesture and costume, as well as in visual art and architecture – whatever it takes to deliver the shock of the hyper-real in order to coerce, to manipulate and to consolidate worldly power. The most flabbergasting example in church history may be the following.

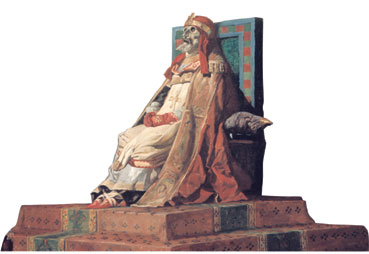

In AD 897, Pope Stephen VII declared that his predecessor, Formosus, had been guilty of assuming the mandate of St Peter under false pretences and by extension performing false ordinations. He had been a bishop elsewhere than Rome, went the charge, and was therefore not eligible, hell mend him! (As ER Chamberlin relates in his 1969 classic The Bad Popes, “the real crime [was that Formosus] had been a member of the opposite faction and had crowned ‘emperor’ one of the numerous illegitimate descendants of Charlemagne after having performed the same office for the candidate favoured by Stephen.”) There was nothing else for it – the bounder was to be dragged to the Vatican and put on trial.

The fact that he had been dead and buried for nine months, however, meant that his defence really hadn’t much going for it, and having been found guilty, the three fingers with which he blessed his flock were chopped off and thrown away, the papal garments with which he had been dressed up were ripped off him and replaced with a hair shirt, and he was hurled headlong into the Tiber by a seething gaggle of peasants.

What on earth was all this about? Ex-priest Peter de Rosa, in his highly entertaining Vicars of Christ:The Dark Side of the Papacy, put the episode down to Stephen’s being “completely mad”. But this madness, I think, did actually contain a kernel of proto-Machiavellian method. Following Stephen’s election, a large portion of the populace of Rome were still in thrall to Formosus, and as street fights, church burnings, executions and massacres had settled many a papal contest since the days of St Peter (Pope Leo III himself had had his eyes and tongue torn out by a dissatisfied mob just earlier that century), he had to find some way to capture and intimidate the public imagination, and assert his ascendancy.

His scheme was shrewd enough, then, anticipating the show trials of Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini in the 20th century. The point being to publicly obliterate an opponent’s legitimacy, and to confirm him as the loser in the most final and horrifyingly visual fashion. The symbolic and the literal, message and medium, became one once more as Stephen rammed home the grand association between decay and disempowerment, appealing to the dog psychology that lies latent in us charming human creatures, awaiting its opportunity to leap free of all previous principle and position and pile in to tear a strip off the already fallen. Stephen must have looked awfully impressive and assured of his holy mandate as he strode around the courtroom bellowing abuse at that putrid, reeking bag of bones. He was strangled to death not long afterward, but his delightful idea had obviously struck a chord. Ten years later poor old Formosus was re-exhumed, re-tried, re-condemned and re-tortured by Pope Sergius, this time having his head lopped off along with three more fingers, before being tossed once more into the Tiber. We can only suppose that he had stopped caring by this point.

It’s too easy, of course, as secular rationalists, to focus on the corrupt vicissitudes and brutalities of the Church, and to dismiss them as the macabre insanity of religious literalism. It makes us a real hoot at parties, but if that’s all we see in religious history and art, we risk neglecting the great aesthetic, philosophical and literary legacies that offer even the modern secularist a comforting poeticisation of human finitude that has been evolved over millennia. Only the most marble-minded atheist will remain uncontemplative and unmoved before the art of the 17th-century Spanish realists on display at the National Gallery, which you really ought to go and see.

The fact is, we humanists, for all our scientific savvy and our rationalisation of the cosmos, don’t do a better job of growing old and dying, and whether we acknowledge it or not, we are deeply in debt to the Judaeo-Christian tradition, to which we owe the profound insight that death, rather than rendering life meaningless, actually bestows meaning; that, despite our subjection to the cruel laws of biology and time, and the suffering they necessitate, it is finitude that renders our experience significant and suffuses our relation to the world and to other beings with joy, wonder and love.

These faith-driven spectacles, in foregrounding death’s inevitable embrace, offer us all a powerful exhortation to revel within life’s limits until they come to meet us. If we can’t make friends with death itself, they tell us, we can perhaps, as Freud hoped, make friends with the necessity of dying, and embrace the richness of experience as it presents itself.