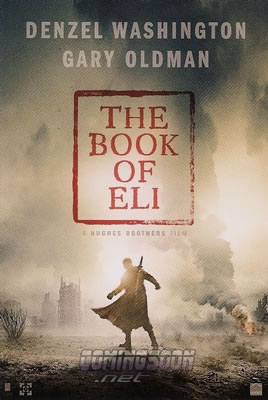

The Apocalypse has happened. Or is happening, if you want to be pedantic about it. People have decided to start eating one another, and it gets so sunny that, if you don't don a pair of surprisingly-cool-circa-2010 shades, you're going to go blind. In the midst of all this, Denzel Washington plays Eli, a bloke with a book, who wanders the land. And the book has a cross on it. And Gary Oldman wants it. This – complex as it may sound – is the plot to The Book of Eli, a not-quite-post-Apocalyptic romp through the wastelands of a deserted America. The film is directed by the Hughes Brothers, and it is their first since From Hell, a poorly received Jack the Ripper comic book movie, from 2001. Lest this colour your impressions of them, however, it must be remembered that they also have under their belts Menace II Society (1993) and Dead Presidents (1995). Still, while The Book of Eli isn't as much as a jump from the settings of those films as From Hell was, it's still something of a change of scene.

The Apocalypse has happened. Or is happening, if you want to be pedantic about it. People have decided to start eating one another, and it gets so sunny that, if you don't don a pair of surprisingly-cool-circa-2010 shades, you're going to go blind. In the midst of all this, Denzel Washington plays Eli, a bloke with a book, who wanders the land. And the book has a cross on it. And Gary Oldman wants it. This – complex as it may sound – is the plot to The Book of Eli, a not-quite-post-Apocalyptic romp through the wastelands of a deserted America. The film is directed by the Hughes Brothers, and it is their first since From Hell, a poorly received Jack the Ripper comic book movie, from 2001. Lest this colour your impressions of them, however, it must be remembered that they also have under their belts Menace II Society (1993) and Dead Presidents (1995). Still, while The Book of Eli isn't as much as a jump from the settings of those films as From Hell was, it's still something of a change of scene.

The Book of Eli is shot very self-consciously, which is not to say 'well', nor does it mean that it was poorly put together. The sun – a constant presence – bleaches the corner of every frame, creating some very swish silhouettes that conveniently come into play when Washington decides to break out his Kung Fu training, and lay his hands on some unfortunate wasteland raider. These silhouettes, along with various other moments, in which impressively-costumed characters form a kind of macho tableau, are the set-pieces between which the film leaps. It has to be said, then, that it does this leaping rather well. Not only that, but the costumes are, generally (save some rather howling anachronisms) very impressive. There is an attention to detail that shows a love for the world in which it is set, and little asides – the correct way to charge an iPod in the wasteland, how to spot a cannibal, what currency is in use – help to give the film a firm foundation, even when the plot and action get a little unsure.

And then there's the Bible. It is no spoiler to reveal that Washington has a final destination on his journey, and the book's preservation is his ultimate goal. Until the film's end, this seems to be a purely humanitarian aim. He even places it alongside the Koran and the Torah. But then odd stuff starts to happen. It seems that, every time one of Gary Oldman's goons shoots at Washington, the lead bounces right off his back. The film's final twist is shocking both for its skilful revelation, and for its audacity. It seems that the Hughes Brothers have had the almighty watching over Washington for the film's duration, giving him powers that are, for lack of a better term, superhuman. Despite Michael Gambon's excellent performance as an old cannibal, then, this rather spoils the movie. Once we learn that every dangerous situation portrayed was not, actually, that dangerous, and that, hey, maybe Denzel didn't need to keep the Bible with him anyway, then the whole thing gets a little preposterous. There is barely any real consideration of how the good book might have little (or, perhaps, greater) relevance in a world where eating baby-stew is the norm. But, then, maybe that's a discussion better had in The Road.

We know where we are with The Road. Man and son, trekking across a dying United States, trying to reach the coast. They are heading east, whilst Denzel Washington is heading west. You could almost imagine them meeting, but it's quite clear that Viggo Mortenson (in a good, if slightly ape-like performance) would probably not emerge from the encounter intact; Washington has a habit of beheading people. Anyway, the superficial similarities between films are myriad. In neither are guns expected to be loaded (ammunition having run out long ago) and in both, long, twisting bridges and elevated highways are the primary method of transportation. Both films, too, place emphasis on the lost art of saying grace, though The Road regards this practice as a little quaint. The religious question comes into play later on, when Mortenson converses with Robert Duvall, playing an unnamed old man who believes that God, if he exists, would turn his back on the destruction that the film depicts. This may seem a more tactful method of addressing the question than that deployed in The Book of Eli (i.e. behead, until nobody's left to disagree), but ultimately both films owe these approaches to their respective inspirations. Whilst The Road cleaves to McCarthy's novel, and is defiantly literary in structure (a voiceover complements the non-events of the plot), The Book of Eli clearly owes more to the videogame, Fallout 3.

We know where we are with The Road. Man and son, trekking across a dying United States, trying to reach the coast. They are heading east, whilst Denzel Washington is heading west. You could almost imagine them meeting, but it's quite clear that Viggo Mortenson (in a good, if slightly ape-like performance) would probably not emerge from the encounter intact; Washington has a habit of beheading people. Anyway, the superficial similarities between films are myriad. In neither are guns expected to be loaded (ammunition having run out long ago) and in both, long, twisting bridges and elevated highways are the primary method of transportation. Both films, too, place emphasis on the lost art of saying grace, though The Road regards this practice as a little quaint. The religious question comes into play later on, when Mortenson converses with Robert Duvall, playing an unnamed old man who believes that God, if he exists, would turn his back on the destruction that the film depicts. This may seem a more tactful method of addressing the question than that deployed in The Book of Eli (i.e. behead, until nobody's left to disagree), but ultimately both films owe these approaches to their respective inspirations. Whilst The Road cleaves to McCarthy's novel, and is defiantly literary in structure (a voiceover complements the non-events of the plot), The Book of Eli clearly owes more to the videogame, Fallout 3.

Yet, as in The Book of Eli, background details are paramount in The Road. In this respect, the films stand toe to toe, in their ability to suggest vaster narratives, through the state in which an abandoned house has been left, or the curve of an overturned lorry on a freeway. Everywhere in The Road, tangential narratives are suggested to the viewer, and it is to director John Hillcoat's credit that he allows these hints to speak for themselves, rather than awkwardly highlighting them.

These little details are the most entertaining elements of both films; what is the exact fate awaiting the cannibals' prisoners in The Road? And just how did Frances De La Tour get hold of that Anita Ward record? Beside these, neither The Road nor The Book of Eli present the audience with a truly engaging or original narrative. In the former, monotone voiceover and saccharine exchanges between father and son prevail, and in the latter, the swiftly rising bodycount soon becomes monotonous. Both Hillcoat and the Hughes brothers have clearly lifted a fascinating location from various sources, and done the apocalyptic wastes great justice in transferring them to the silver screen. Ultimately, however, none of these filmmakers has managed to tell a story worthy of such a brutally realised setting.